This post revised November, 2022.

1. The 15th and 16th centuries

The idea of Fortune as controlling a wheel that turns up and down unpredictably has its roots in ancient Greece and Rome. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century b.c.e, said, “Men's fortunes are on a wheel, which in its turning suffers not the same man to prosper for ever” (A. D. Godley, translator [1931, in archive.org], Herodotus, Histories, vol. 1, book 1, section 207, p. 261). In the same vein, Ammianus Marcellinus (Historia, XXVI, 8) said, “Anyone who is prosperous may by the turn of fortune's wheel become most wretched before evening.” The philosopher and playwright Seneca expressed the same sentiment in numerous ways, as did many others.

Wikipedia cites numerous historical examples starting from the first century b.c.e. and likely reflecting earlier times. Its first is the zodiac, called "the wheel of fortunes"; it "moves from east to west/ and includes each of the twelve signs of fortune, the signs of the zodiac." Given that the zodiac was used for telling fortunes in ancient Babylon, it is possible that the idea of a "wheel of fortune" goes back that far.

The typical attitude toward Fortune, now personified as a fickle goddess, Fortuna in Latin, Tyche in Greek,is expressed by a Roman tragedian of the 1st century b.c, Pacuvius (Scaenicae Romanorum Poesis Fragmenta. Vol. 1, ed. O. Ribbeck, 1897, trans. Jamie Lee Edwards, Still Looking for Pieter Breugel the Elder, M. Phil.(B) thesis, University of Birmingham, 2013, which also gives the original Latin, online):

Philosophers say that Fortune is insane and blind and stupid, and they teach that she stands on a rolling, spherical rock: they affirm that, wherever chance pushes that rock, Fortuna falls in that direction.They repeat that she is blind for this reason: that she does not see where she's heading; they say she's insane, because she is cruel, flaky and unstable; stupid, because she can't distinguish between the worthy and the unworthy.In the Middle A

ges, the most influential application of this concept was that of Boethius in his Consolation of Philosophy (trans. Peter Walsh, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 20, in Google Books), 6th

century c.e.

ges, the most influential application of this concept was that of Boethius in his Consolation of Philosophy (trans. Peter Walsh, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 20, in Google Books), 6th

century c.e. Having entrusted yourself to Fortune's dominion, you must conform to your mistress's ways. What, are you trying to halt the motion of her whirling wheel? Dimmest of fools that you are, you must realize that if the wheel stops turning, it ceases to be the course of Fortune.The remedy was not to value the things of this world, but rather to focus on that which is eternal.

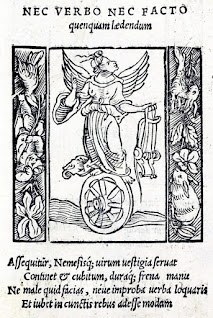

Another goddess with a wheel was Nemesis (at right above), who acted on behalf of the gods to bring down those whose pride went so far as to challenge the gods. I will say more about her in relation to the Wheel of Fortune later.

One of the earliest medieval illustrations still preserved contains lines that would later become incorporated into the tarot’s Wheel. In a drawing from late 9th century Spain now in Manchester, England (John Ryland Library, ms. 83, folio 214v): regnabo, regno, regnavi, and sum sine regno: I shall reign, I reign, I have reigned, and I am without reign”. We will see similar words in the tarot.

In the earliest known tarot Wheel of Fortune, that of the Brera-Brambilla (Brera Gallery, Milan, far left below), done for a member of the Visconti family before Duke Filippo Maria Visconti's death in 1447. The words are not there, but we do see something else, namely donkey ears on the one going up and the one on top, a pictorial commentary on the foolishness that strikes people who are in authority

("on top") or expect to be so. The one going down and the one on the

bottom are noticeably without such ears.

("on top") or expect to be so. The one going down and the one on the

bottom are noticeably without such ears.The same is true in the next known Wheel, that of the Visconti-Sforza card (Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, near left). Although not easy to make out against the brown background, the one going up and the one on top again have donkey ears; and although the one going down lacks the ears, he does have a tail; these are symbolic features that ar surprisingly persistent in the tarots that follow. The only fully human figure is the one at the bottom. Very faint so many centuries later are the banners that accompany the figures: Regnabo, Regno, Regnavi, Sum sin regno.

Now we see why there were no donkey ears on the one going down in the earlier tarots of the Visconti and Sforza, although more ambiguously: he has grown wiser and more human as a result of his fall, even if he still retains an ass’s hindquarters; in contrast, on the way up his head was filled with asinine notions, and ifQuella ruota dipinta mi sgomenta

ch’ogni mastro di carte a un modo finge:

tanta concordia non credo io che menta.

Quel che le siede in cima si dipinge

uno asinello: ognun lo enigma intende,

senza che chiami a interpretarlo Sfinge.

Vi si vede anco che ciascun che ascende

comincia a inasinir, le prime membre,

e resta umano quel che a dietro pende.

(That painted wheel dismays me

that every card maker paints in the same way:

And such concord I believe is not a lie.

For that which sits on top they paint

A little ass: everyone understands the riddle,

without calling on the Sphinx to interpret.

We also see that each one that ascends

begins to assify his upper members,

and the one who hangs below stays human.)

he succeeded in reaching the top his asininity was complete. In the earlier tarots, which after all were commissioned by members of the Visconti and Sforza ruling family of Milan, the satire is more a warning than a judgment, since most of the head remains human. In all three of these, however, it is the one on the bottom who is fully human, even if he only possesses enough to cover his nakedness.

he succeeded in reaching the top his asininity was complete. In the earlier tarots, which after all were commissioned by members of the Visconti and Sforza ruling family of Milan, the satire is more a warning than a judgment, since most of the head remains human. In all three of these, however, it is the one on the bottom who is fully human, even if he only possesses enough to cover his nakedness.Another early tradition had fully human figures for the ones climbing and descending, but an animal face on the one on top; an example is that of a ca. 1500 uncut sheet thought to be from Bologna, at left. This is perhaps a comment on the nature of power, that when it is a matter of animal force rather than human intelligence, it is as vulnerable as an animal is to human weapons.

This way of seeing the Wheel of Fortune, with its ups and downs, as a warning rather than an inevitability is characteristic especially of Renaissance Florence. Most noteworthy is a 1480s letter of Marsilio Ficino to Giovanni Rucellai, a rich merchant of the city who was concerned about the stability of his fortunes. Aby Warburg called attention to it in an essay published in 1932; Ficino's Italian was later translated into English for the English edition of some of Warburg's writings. Ficino wrote (pp. 256-257 of Warburg's Renewal of Pagan Antiquity, ed, Kurt Forster, trans. David Britt, 1999, Gerry Research Institute, Los Angeles, currently online in the Getty's "virtual library" and (without page numbers) in Google Books):

You ask whether man can influence or in any way remedy future events, and in particular those events that are deemed fortuitous. I am certainly of two minds on this matter. For when I consider the uncertain lives of the wretched common herd, I see that foolish people take no thought for the future; if they do take thought, they do not provide for a remedy; or else, if they do seek to improve maters, their efforts are of little or no avail. So that when I think of them, my opinion is that Fortune is irremediable. On the other hand, if I turn my mind to the works of Giovanni Rucellai and others, whose lives are governed by prudence and moderation, I see that things to come can be foreseen, and things foreseen can be remedied. When I consider this, my mind reverses its former opinion. This distinction amounts, it seems, to the following initial conclusion: that the blows of Fortune are not to be resisted by man or by human nature, but only by a provident [prudente=prudent] man and by human providence [prudenzia].Even then, Ficino adds, “a provident [prudente] man has power against Fortune, but with the gloss that was set upon it by that wise man, ‘Thou couldest not have the power except it were given thee from above' [John 19:11]." So Fortune must bow to Providence, in the sense of a beneficent power from God.

After more discussion, Ficino concludes (Ibid, p. 258):

It is good to do battle with Fortune, wielding the weapon of providence, patience, and noble ambition [magnanimità=magnanimity]. It is better to withdraw, and to shun such a combat—from which so few emerge victorious, and then only after intolerable labor and effort. It is best of all to make peace or a truce with Fortune, bending our wishes to her will and willingly going the way that she directs, lest she drag us by force. All this we shall do, if we can combine within ourselves the might [potenza, also power], the wisdom, and the will. Finis. Amen.By a truce [“triega”], however, Ficino did not mean surrender, but rather accommodation, achieving one’s desires to the extent they are within the limits set by Fortune. It is the reconciliation of two opposites, victory and surrender. Even then there remains a tension, which Warburg characterizes as: (“Francesco Sassettis letztwillige Verfügung,” in Erneuerung Der Heidnischen Antike, Band I, Leipzig, 1932, p. 151 [“Francesco Sassetti’s Last Injunction to his Heirs,” in The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity, p. 242]).

eine plastische Ausgleichsformel zwischen ‘mittelalterlichem’ Gottvertrauen und dem Selbstvertrauen des Renaissancemenschen . . . einen neuen mittleren Zustand der Selbstbehauptung an, gleich weil entfernt von mönchisch-weltflüchtiger Askese, wie von weltbejahender Renommage.The position of the Wheel of Fortune in the tarot sequence reflects this tension between the concerns of this world and those of the next. It was mostly tenth in the series, or eleventh if the Fool counts as first, sometimes one less or more, but always approximately midway. Below the Wheel are the cards of achievement within the practice of virtue; after it come the Old Man (soon to die), the Hanged Man (who is about to die), Death, and images of things that were considered eternal and unchanging.(It is true that Temperance paradoxically appears in some lists after the Death card -- what need has a dead man for temperance?-- but this is in only one center of the tarot, Milan, and perhaps the image had other connotations, pertaining to the soul rather than the body.) Before the Wheel, the tarot looks to this world, afterwards, to the next. Both must be taken into consideration. Hence the necessity of conducting oneself virtuously, restraining one's material desires with Temperance, treating others with Justice, bearing misfortune with Fortitude, practicing Charity, and maintaining Faith and Hope in the world to come. Prudence in particular allows one to foresee the vagaries of Fortune: hence an interpretation of the Old Man as Prudence, as by Piscina in 1565 (see my post on that card), is a logical one in relation to its place in the sequence, coming immediately after the Wheel.

an iconic [literally, graphic] formula of reconciliation between the ‘medieval’ trust in God and the Renaissance trust in self . . . a new equilibrium, a state of self-assertion that would be equally remote from monkish, unworldly asceticism and from worldly [literally, world-affirming] self-conceit [literally, rewards].

In relation to Temperance, this way of minimizing the effects of Fortune in this life was expressed in comments about Nemesis. Alciato in his Emblemata of 1531 showed her with a bridle (at right), which also was an attribute of Temperance, for example in Giotto's famous ca. 1305 allegorical paintings of the seven virtues in the Scrovegni Chapel at Padua (at https://www.wikiart.org/en/giotto/temperance and elsewhere; the bit is in her mouth, the reins across her cheeks).

In relation to Temperance, this way of minimizing the effects of Fortune in this life was expressed in comments about Nemesis. Alciato in his Emblemata of 1531 showed her with a bridle (at right), which also was an attribute of Temperance, for example in Giotto's famous ca. 1305 allegorical paintings of the seven virtues in the Scrovegni Chapel at Padua (at https://www.wikiart.org/en/giotto/temperance and elsewhere; the bit is in her mouth, the reins across her cheeks).

Alciato's words below the picture read (Emblemata, Augsburg 1531, p. A7r; translated at website "Alciato at Glasgow," https://www.emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/alciato/emblem.php?id=A31a014):

Nemesis follows on and marks the tracks of men;

In her hand she holds a measuring rod and harsh bridles.

She bids you do nothing wrong, speak no wicked word,

And commands that moderation be present in all things.

And above it:

Injure no one, either by word or deed.

So be temperate in your desires, or Nemesis will exact retribution. She is here not a blindfolded goddess, but an agent of the gods.

In this way the medieval attitude toward Fortune, that of an arbitrary and merciless force, was somewhat overcome during the Renaissance. Fortune, if guided by prudence, justice, fortitude, temperance, and the other virtues, offers tangible rewards, but we must also take into consideration the transient and undependable nature even of rewards justly won. Being temperate in our desires is one way to get a respite from Fortune and Nemesis, while still recognizing their ultimate control over our earthly lives.

One of the first figures to be seen is a winged, naked goddess standing on top of a sphere, with a group of people below her on two sides. In "Version A" of 1521 (above), done after a design by Hans Holbein the Younger and probably under his supervision, anxious, grasping people on the right look up at what she holds in one hand, a trophy cup. On the left side, mostly calm but well dressed people look up at what she holds in her other hand, a bridle. Another frontispiece from the same year, "Version B" (at left), captures the same idea with fewer figures. The idea is surely that by restraining one's desires one can achieve calmness and also prosper sufficiently, whereas by going for large rewards where there is less chance of success, the result is mostly anxiety and poverty.

This idea of the happy people being on one side and the sad on the other, neither of whom are actually very admirable, is reflected in the text of the allegory that the frontispiece illustrates:

“But tell me, who can be that woman, who seems to be both wild and blind, standing on a globular shaped stone?'The text does not say that she holds anything in her two hands; those details would seem to be a Renaissance innovation, perhaps based on depictions of Nemesis, not only Alciato's but also one by Dürer in around 1508 (at right), which shows the goddess, merged with Fortune, holding a goblet in one hand (favor) and a bridle in the other (castigation) (Panofsky, Life and Art of Albrecht Durer, 1955, p. 81, in archive.org).

“Her name,” answered he, “is LUCK; not only blind and wild is she, but deaf”

“And what might her business be?”

“She circulates everywhere,” said he. “From some she takes their substance, and freely gives it away to others. Then, again, she suddenly withdraws what she has given, and gives it to others without any plan or steadfastness. So you see that her symbol fits her perfectly.”

“Which symbol?” asked I.

“Why, the Globular Stone on which she stands.”

“And what does that betoken, I wonder?”

“That Globular Stone signifies that no gift of hers is safe or lasting, for whosoever

reposes any confidence in her, is sure to suffer great and right grievous misfortune.”

:”What is the wish and the name of that great multitude standing around her?”

“Oh! they are known as the UNREFLECTING, they who desire whatever Luck might throw them.”

“But then, how is it that they do not behave in the same manner? For some seem to rejoice, while others are agonizing, with hands outstretched?”

“Well, those who seem to rejoice and laugh are they who have received somewhat from her, and you may be sure that they call her FORTUNE! On the contrary, those who seem to weep and stretch out their hands are they from whom She has taken back what She had given. They call her MISFORTUNE!

“And what sort of things does She deal in, that they who receive them laugh, while they who lose them, weep?

“Why, what to the great multitudes seems Good, of course: Wealth; then Glory, Good Birth,Children, Power, Palaces, and the like.”

“But such things, are they not really good?”

That question, let us postpone.”

“Willingly,” said I. (From The Greek Pilgrim's progress, generally Known as The Picture, by "Cebes (of Thebes)", trans. Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie (Yonkers, NY: Platonist Press, 1910, p. 7, in archive.org.)

The tension between the two attitudes toward Fortune, as somewhat manageable (Cebetis Versions A and B) versus unmanageable (Version D), would seem to be the tension between two views of life, monkish disdain for the world, from the Middle Ages (D, which disdains Fortune altogether), and restrained self-affirmation in the world (A and B, for the side of the bridle), reflecting the Renaissance.

In 1565 Francesco Piscina wrote about the Wheel card (Discorso, in con gli occhi e con l'intelletto: Explaining the Tarot in Sixteenth Century Italy, ed. Ross Sinclair Caldwell, Thierry Depaulis, and Marco Ponzi, Lulu:2018, pp. 20-21):

Finally in the tenth place the image of Fortune is placed. I believe that the author meant that, although Popes and Emperors are great, strong, and powerful, their honours, triumphs, powers and greatness, and in general all these earthly things and any other temporal good, are subject to the insolence of Fortune. So what Ariosto has written in his third Canto is no less prudent than elegant:

Fortune gives and takes everything,

only on virtue it has no power.

This is of course the sentiment of Boethius, numerous medieval texts, and the Tabula Cebetis text, albeit without the nuances that Ficino articulated.

Piscina devotes another paragraph to the question of why Fortune has a higher position in the sequence than Justice. His answer is that on earth justice is administered very imperfectly, sometimes well and sometimes poorly, so that chance often dominates.

The anonymous treatise of around the same time but from a different region says that Fortune is what courtiers blame or praise depending on their reception by the court to which they are attached. Actually, the writer retorts, they have mainly themselves to blame, if their service is found wanting, or if not, then the poor judgment of the one doing the rewarding. In reality much depends on a hidden affinity between people that can cause poor service to be rewarded without justification.

Both of these authors make explicit a connection between Justice and Fortune, with the implication that Fortune seems often opposed to the demands of Justice. While the one accepts this at face value, the other says that the apparent arbitrariness of fortune actually is caused by the weaknesses of men. Another view is that justice is in fact served, even if we do not know why. Still another is that Fortune is guided by divine Providence, which takes a longer view. than our limited and self-centered perspective.

2. The Wheel in 17th-18th century France

Another change occurs in mid-17th century Paris. The fourth person, the one under the wheel, has been removed and the men on the two sides, who were only part donkey before, now are metamorphosed into fantastic animals..Yet I think we can still recognize the origins of these animals in what came before.  The one going down has a human face and is animal behind, just like the one going down on the earlier Italian cards. Likewise the one going up has an animal face, even if his legs and feet have been transformed into weird shapes not seen in nature. It is possible that the idea of wrapping the legs of the one on the right around the rim of the wheel may have come from a illustration for Brandt's Der Naarshiff (The Ship of Fools).

The one going down has a human face and is animal behind, just like the one going down on the earlier Italian cards. Likewise the one going up has an animal face, even if his legs and feet have been transformed into weird shapes not seen in nature. It is possible that the idea of wrapping the legs of the one on the right around the rim of the wheel may have come from a illustration for Brandt's Der Naarshiff (The Ship of Fools).

The one on top is still clearly a king, thus exemplifying the verb "regno", meaning "I reign." That the other two are more animal-looking than previously suggests more strongly that both sides are based on material desires, and that to seek the favor of an earthly king is to invite disaster, since he who raises one up will most likely send one down again. It is perhaps a reflection on the French absolutism of the time, exemplified most memorably by Louis XIV.

This king seems to replace the old figure of Fortune in the middle of the wheel, as though to suggest that kings are as unpredictable as Fortune. On the other hand, given the images of Fortune on her Wheel, or a sphere, he could also be taken as the agent of Nemesis, elevating the good and dismissing those whose virtue proves inadequate.

Noblet's card seems to start and end in water. The suggestion might be that having fallen from grace wiser and chastened, one can still pick oneself up and try again. It also suggests the course of human life, being born out of unknown depths, rising up to some sort of mastery by mid-life and then falling again into the depths. That is a course described in ancient times by Plutarch and will be described again by Jung. Here is Plutarch on the "sistrum", a kind of rattle used in Isaiac processions (Isis and Osiris, section 63, at (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/Isis_and_Osiris*/D.html#T375b):

The upper part of the sistrum is circular and its circumference contains the four things that are shaken; for that part of the world which undergoes reproduction and destruction is contained underneath the orb of the moon, and all things in it are subjected to motion and to change through the four elements: fire, earth, water, and air. At the top of the circumference of the sistrum they construct the figure of a cat with a human face, and at the bottom, below the things that are shaken, the face of Isis on one side, and on the other the face of Nephthys. By these faces they symbolize birth and death, for these are the changes and movements of the elements; and by the cat they symbolize the moon because of the varied colouring, nocturnal activity, and fecundity of the animal.

It is quite possible that this passage influenced the occultists' idea that the wheel was that of Ezekiel, who saw wheels with four faces on them, of figures later associated with the four elements. In any case, there is birth at the bottom on one side, and death on the other. But what of the symbol representing the ever-changing moon, "the cat with a human face"?

I would call attention to the top figure of Dürer's Wheel, who is reaching for a round object above him. It would seem to be the moon, another image of ever-changing fortune.

At some point, perhaps as late as the early 18th century, a change occurred at the top of the wheel: the king on top resembled an Egyptian sphinx, with its long tail, a beard like those on Egyptian sculptures of pharaohs, and winglike banner behind (at right, Chosson of 1672 or 1736). This is not a house cat, but a lion is a kind of cat, too. On the one hand, we might think of Ra, the king of the Egyptian gods, who finally elevates Horus to Kingship over Egypt, presumably sending Typhon to the Underworld. On the other hand, there is the Sphinx of the Oedipus legend. The beard and crown suggest a masculine figure, roughly corresponding to what could be seen at that time at Giza, namely just the head and neck (the rest buried in sand). The cape/wings (with the parallel lines as feathers) conforms to the Greek version, which is female. That the latter version was known in 17th century Paris is confirmed by the small sphinx in the Pope card of the anonymous tarot of Paris a little before Noblet (see my post on that card), with wings and large female breasts. The Marseille-style sphinx has aspects of both versions.

At some point, perhaps as late as the early 18th century, a change occurred at the top of the wheel: the king on top resembled an Egyptian sphinx, with its long tail, a beard like those on Egyptian sculptures of pharaohs, and winglike banner behind (at right, Chosson of 1672 or 1736). This is not a house cat, but a lion is a kind of cat, too. On the one hand, we might think of Ra, the king of the Egyptian gods, who finally elevates Horus to Kingship over Egypt, presumably sending Typhon to the Underworld. On the other hand, there is the Sphinx of the Oedipus legend. The beard and crown suggest a masculine figure, roughly corresponding to what could be seen at that time at Giza, namely just the head and neck (the rest buried in sand). The cape/wings (with the parallel lines as feathers) conforms to the Greek version, which is female. That the latter version was known in 17th century Paris is confirmed by the small sphinx in the Pope card of the anonymous tarot of Paris a little before Noblet (see my post on that card), with wings and large female breasts. The Marseille-style sphinx has aspects of both versions.

Here some human characters, in the form of Monkeys, Dogs, Rabbits, etc. ascend in turn upon this wheel to which they are attached; one would say it is a satire against fortune & against those whom she rapidly lifts up & those she allows to fall again with the same rapidity.

Except for the particular identification of the animals, this explanation is perfectly conventional and medieval. De Gebelin has not recognized that the one ascending is a deformed donkey, and the one descending has a deformed human face. The allegory of the earliest cards has been lost, or at least made harder to see.

An odd feature of this style of card, the so-called TdM (Tarot de Marseille) II, is that the left side of the wheel's axis, and the left vertical support, are missing. This is not true of Noblet's, an earlier variant called TdM I. My speculation is that an earlier version may have lost some of its wood through wear, so that there was no ink at  these places; either that or the figure going down, with its human torso, took up much more space, thus obscuring the support next to him and perhaps also confusing the cutter; in the Vieville (at right), of the same time period as the Noblet, shows both supports, but the one next to the figure going down is rather foreshortened.

these places; either that or the figure going down, with its human torso, took up much more space, thus obscuring the support next to him and perhaps also confusing the cutter; in the Vieville (at right), of the same time period as the Noblet, shows both supports, but the one next to the figure going down is rather foreshortened.

Etteilla (at right, in a 1969 reprint)

gives us a crowned monkey, on top waving a baton, as though an

animal-tamer, and on a ring below, a mouse or rat climbing and a man going down. Remembering that this card was produced in 1788, and that the monkey wears a crown, it is likely a satire against the monarchy and those who jump

to its tune. A mouse in French (and English) conventional

metaphors is a person who is careful around authority but when it is

gone will have a good time: "Quand

le chat n'est pas là, les souris dansent," literally, "When the cat is

not there, the mice dance." The card thus seems a call to liberate humanity through political revolution. Etteilla was in fact a fervent supporter of the Revolution of 1789, although he died before its more extreme phases. On the other hand, if a rat is going up and a man down, that is is a comment on society. In his 3rd Cahier Etteilla comments that the card means "increase and fortune; note however that every time it appears in a spread, you should not

believe that it is ours" (translation at http://thirdcahier.blogspot.com/).

3. The 19th and early 20th century occultists

Eliphas Lévi drew his own version of the card, one of only a very few done by him. He says (Transcendental Magic: its Doctrine and Ritual, trans. Waite, p. 367, with my corrections, from Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie, Vol. 2, 1861, pp. 350-1; both in archive.org):

Hieroglyph, The Wheel of Fortune, that is to say, the cosmogonic wheel of Ezekiel, with a Hermanubis ascending on the right, a Typhon descending on the left, and a sphinx in equilibrium above, holding a sword between it's lion's claws. An admirable symbol, disfigured by Etteilla, who replaced Typhon with a wolf [homme = man], Hermanubis with a mouse, and the sphinx by an ape. An allegory characteristic [digne = worthy] of Etteilla's Kabbala.

Ezekiel's vision of course did not include any of these creatures. Typhon, originally the name of a monster in Greek mythology, then applied to the evil brother of Osiris, is the figure that de Gebelin had identified with the Devil, the evil principle of Plutarch's Isis and Osiris. In that legend he is the murderer of Osiris, who is avenged by his son Horus. Hermanubis is a Greek name for a hybrid of the Egyptian god Anubis and the Greek Hermes. He is the jackal-headed god who oversaw embalming and led the soul to the judgment hall in the afterlife. Plutarch said he was the son of Osiris and Nephthys, when the latter took the form of Isis so as to deceive Osiris and induce him to have intercourse with her. Nephthys, however, abandoned the infant; he was rescued by Isis and raised by her as his own.

All of this fits Plutarch's account of the side of the sistrum that represents Isis. He says, in the sentence before the passage just quoted, about the sistrum (still section 63):

They say that they avert and repel Typhon by means of the sistrums, indicating thereby that when destruction constricts and checks Nature, generation releases and arouses it by means of motion.The editor refers us to an earlier passage (section 59) in which Plutarch says:

the fable has it that Typhon cohabits with Nephthys and that Osiris has secret relations with her, for the destructive power exercises special dominion over the outermost part of matter which they call Nephthys or Finality. But the creating and conserving power distributes to this only a weak and feeble seed, which is destroyed by Typhon, except so much as Isis takes up and preserves and fosters and makes firm and strong.

This last is a reference to Anubis, the child of Osiris and Nepthys rescued by Isis, who thus corresponds to the side of the sistrum, now the Wheel, on the side of Isis, escaping the destructive power of Typhon on the side of death. On that side also would be Horus, also protected by Isis against the murderous designs of Typhon.

Next to Hermanubis is the word Azoth, a term for alchemical Mercury, from the Arabic name for that substance (see Wikipedia's entry). It was also known as the Alpha and Omega, or A to Z, and so corresponded to Christ. The word next to Typhon is Hyle, Greek for matter, which without form is chaotic and destructive. Azoth in alchemy, as the universal elixir, is equivalent to the redeemer in religion, or more fully, as Levi proclaimed (Transcendental Magic, Waite translation, pp. 264-265):

The universal medicine is, for the soul, supreme reason and absolute justice; for the mind, it is mathematical and practical truth; for the body, it is the quintessence, which is a combination of gold and light. In the superior world, the first matter of the great work is enthusiasm and activity; In the intermediate world, it is intelligence and industry; in the inferior world, it is labour; in science it is sulphur, mercury, and salt, which, volatilised and fixed alternately, compose the Azoth of the sages.

The word next to the sphinx is Archée, a word otherwise meaning "immaterial principle of organic life." When Levi talks of the sphinx elsewhere in his book, it is in the context of the Oedipus legend as told by Sophocles, where she is a poser of riddles, granting kingship over Thebes if they were successful and immediate death if they were not. Levi says that her riddle must be understood in more than one sense: it is not only "What is that animal which in the morning has four feet, two at noon, and three in the evening?" but also "How is the tetrad changed into the duad and explained by the triad?" and "How does the doctrine of elementary forces [i.e. the four elements - MH] produce the dualism of Zoroaster, while it is summed by the triad of Pythagoras and Plato?" (all Waite trans. p. 15). When Oedipus answers "man," he wins the kingship but also falls into a trap. Wirth comments: "Unfortunate! He has seen too much, and yet with insufficient clearness; he must presently expiate his calamitous and imperfect clairvoyance by a voluntary blindness."

Although Oedipus rules well and raises a large family with his wife (and mother, unknown to him), a plague descends on Thebes. Investigating the cause, he soon finds that it is himself, having killed his father and married his mother, two grave violations of divine law. Levi comments (p. 16 of Waite trans., pp. 88-89 of 1861 French version):

the crime of the King of Thebes was that he failed to understand the sphinx, that he destroyed the scourge of Thebes without being pure enough to complete the expiation in the name of his people. The plague, in consequence, avenged speedily the death of the monster, and the King of Thebes, forced to abdicate, sacrificed himself to the terrible manes of the sphinx, more alive and voracious than ever when it had passed from the domain of form into that of idea. Oedipus divined what was man and he put out his own eyes because he did not see what was God. He divulged half of the great arcanum, and, to save his people, it was necessary for him to bear the remaining half of the terrible secret into exile and the tomb.The moral: "Everything is symbolical and transcendental in this titanic epic of human destinies" (Ibid.). Oedipus's unknowingly killing his father is symbolically the "alarming prophecy of the blind emancipation of reason without science" (pp. 14-15), so that his fate - voluntary blindness, then vanishing in the storm - is that of "all civilizations which may at any time divine the answer to the riddle of the sphinx without grasping its whole import and mystery" (p. 15). (By "science" Levi of course means esoteric science.) Instead of killing the sphinx, Levi says, he should have harnessed her to his chariot. Then he would have avoided incest, and all would have been well. "We come not, like Oedipus, to destroy the sphinx of symbolism; we seek, on the contrary, to resuscitate it," Levi says later (p. 385).

The initiate, therefore, must aspire to the sphinx in its higher meaning (p. 31):

He who aspires to be a sage and to know the great enigma of nature must be the heir and despoiler of the sphinx; his the human head in order to possess speech, his the eagle's wings in order to scale the heights, his the bull's flanks in order to furrow the depths, his the lion's talons to make a way on the right and the left, before and behind.

The sphinx, as he understands it, has a human head, an eagle's wings, a bull's haunches, and the lion's claws. He has more, but that is enough to get a sense of his perspective on the card.

Levi's student Paul Christian qualifies Hermanubis as "the Spirit of God," Typhon as "the spirit of Evil"; as for the sphinx:

It personifies Destiny ever ready to strike left or right; according to the direction in which it turns the wheel the humblest rises and the highest is cast down.

As the personification of Destiny, the sphinx could well be that of Oedipus, for she is the agent of his destiny, by which he unwittingly marries his mother. Christian has a profound-sounding sentence at the end of his short commentary.

To possess Knowledge and Power, the will must be patient; to remain on the heights of life--if you succeed in attaining them--you must first have learned to plumb with steady gaze vast depths.

This is from the perspective of the sphinx on the card. Presumably the meaning is that to stay in the high understanding represented by the sphinx one must be able to withstand looking down at the serpents emerging from the two boats on a featureless sea, and perhaps below that sea as well. Serpents were symbolic both of evil and wisdom. The wise know the evil of which men are capable.

Papus puts the card in the context of Hinduism: it represents the law of Karma in the round of incarnations. It is also the principle of Vishnu, preservation. Karma is a kind of balancing force in the universe that gives evil for evil done and good for good done.

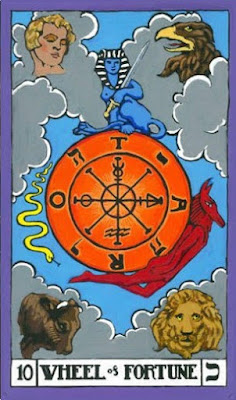

Wirth develops Papus's perspective, using the image both of them inherited from Levi. There are six spokes on the TdM Wheel. On Levi's are there seven or perhaps eight, if a spoke is hidden by the Wheel's support. Waite and Case will opt for eight, so as to accommodate two sets of four, for ROTA and JVHV. Wirth opts for seven, for the seven planets of astrology. There are two circles on the wheel, rotating in opposite directions, he says, probably referring to Ez. 1:16 (although there is no indication of direction):

et aspectus earum et opera quasi sit rota in medio rotae.

(and their appearance and their work was as it were a wheel in the midst of a wheel.)

Here is what Wirth says (2012 English ed., p. 95):

it shows us a wheel with two concentric rims, the image of the double whirl which generates the life of each individual. This life is engendered like an electric current as soon as a wheel, checked in its movement, takes the opposite direction in the girating movement around it. The individual is the result of the force opposing everything of which he is in fact a part. He only becomes the central point by rebelling against universality. . . . He only manages to a limited extent, hence the brevity of individual existence to which the wheel of Fortune alludes. . . . After the precipitation of the strong rhythm of youth comes the calm regularity of maturity, then the decline into old age which ends in a fatal and complete standstill.

Such is the Wheel of Destiny for each individual, moving in opposition to the universal, even if it is also part of that universality. On the left is "the Hermanubis holding the caduceus of Mercury, on the left "a Typhonic monster armed with a trident"; the former symbolizes "all the beneficial and constructive energies which favor the growth of the individual"; the latter is "the destructive agents which the living person must resist." It is also Hyle, "the fire of selfish passion and the spirit of chaotic matter", astrologically Capricorn and a symbol of fallen man, subsequently "regenerated in the water of baptism", apparently the green waves at the bottom, which he also calls "the somber ocean of chaotic life." On it are two boats whose shape "reminds us of Isis," from which two snakes rise up, male and female, which become propulsion (red) and sensitivity (green). Astrologically they correspond to Aries and "the awakening of life in spring." Then one may rise gain with Hermanubis, which "corresponds to the Azoth of the Wise, an ethereal substance which penetrates all things, to excite, support and revitalize if need be, the movement of life."Astronomically it is the dog-star rising at the summer solstice, the beginning of Cancer. (All from pp. 96-97.)

At the top, the equilibrium between the two, astronomically at Libra, is the sphinx, of which he says (p. 96):

It is the Archeus of the Hermetists, the fixed and determining core of individuality, in the centre of which burns Sulphur, corresponding to the sign of Libra between the two solstices.Wirth is drawing an analogy between the Sphinx, with its sword, and Justice, as depicted on its card. Like Levi, he sees the four creatures of Ezekiel's vision merged in the sphinx. To indicate the corresponding elements, he colors the wings blue (air), the chest and front legs green (water), the hindquarters black (earth), and head red (fire). At the center of the Archeus, which is "the fixed and determining core of individuality," burns Sulphur. "This principle of unity," Wirth explains, "has power over elementary attractions [the four elements] which it synthesizes and converts into vital energy."

It also seems of some interest that if red is energy that propels, then it is Typhon that propels the wheel - it does so, however, in the direction of chaos. Hermanubis, with no red, merely receives, with the intelligence signified by his yellow color. What it receives, moreover, is from above, signified by his blue upper body. But without heat, air does not rise. In that way the soul is always both: acting in the world and receiving from what is above.

In Waite's version of the card, interestingly, the colors reverse. Red is the color of the Anubis going upwards, and yellow the color of the other side, now a serpent rather than a devil. Intelligence is on the side of the serpent, as opposed to energy on the side of the Anubis. Also, probably as a result of Levi's identification of the Wheel with Ezekiel's, Waite has added the four "faces" of the celestial chariot: those of the Lion, the Ox, the Eagle, and the Man, inserted into the four corners of the card, using a style of representation earlier given only to the World card. As the Book of Ezekiel has it, 1:10 and 1:15, in the Vulgate:

In Waite's version of the card, interestingly, the colors reverse. Red is the color of the Anubis going upwards, and yellow the color of the other side, now a serpent rather than a devil. Intelligence is on the side of the serpent, as opposed to energy on the side of the Anubis. Also, probably as a result of Levi's identification of the Wheel with Ezekiel's, Waite has added the four "faces" of the celestial chariot: those of the Lion, the Ox, the Eagle, and the Man, inserted into the four corners of the card, using a style of representation earlier given only to the World card. As the Book of Ezekiel has it, 1:10 and 1:15, in the Vulgate:

similitudo autem vultus eorum facies hominis et facies leonis a dextris ipsorum quattuor facies autem bovis a sinistris ipsorum quattuor et facies aquilae ipsorum quattuor . . . cumque aspicerem animalia apparuit rota una super terram iuxta animalia habens quattuor facies

(And as for the likeness of their faces: there was the face of a man, and the face of a lion on the right side of all the four: and the face of an ox, on the left side of all the four: and the face of an eagle over all the four. . . . Now as I beheld the living creatures, there appeared upon the earth by the living creatures one wheel with four faces.).

These four also are associated with the four elements and the zodiacal signs of Leo, Taurus, Aquarius, and Scorpio (for which the eagle is held to substitute). According to Case, the four creatures symbolize the four letters of JHVH, the power above all. After the Book of Revelation adopted the same schema (Rev. 4:7-8), the four animals also came to be understood as representing the four evangelists. Waite's card, in that it gives them books, would seem to refer to the evangelists more than to Ezekiel, but both can be implied easily enough.

Waite adds, intentionally giving precedence to Levi:

With the French occultist [i.e. Levi], and in the design itself, the symbolic picture stands for the perpetual motion of a fluidic universe and for the flux of human life. The Sphinx is the equilibrium therein. The transliteration of Taro as Rota is inscribed on the wheel, counterchanged with the letters of the Divine Name--to shew that Providence is implied through all. But this is the Divine intention within, and the similar intention without is exemplified by the four Living Creatures.

So for Waite the letters JHVH on the Wheel - and apparently the four creatures with "similar intention" - symbolize Divine Providence. Even in the "flux of human life" Providence is working.

The identification of the Wheel with Providence is perhaps made so as to counteract the view, expressed in ancient Epicureanism, that what happens in the universe, apart from what living beings make of it, is merely cause and effect working itself out aimlessly. That it is Providence implies that what happens is arranged so as to lead us to our proper destination, i.e. salvation, whether we know it or not. Hence the appropriateness of the four evangelists for Waite's very Christian perspective.

For both Waite and Case, the Wheel shows, on its spokes, the symbols for the three basic concepts in alchemy: salt,

sulphur, mercury, to which the Golden Dawn added water, the principle of

dissolution, to make four. According to Case, salt (on the left) corresponds to inertia, the dominant quality of subconsciousness; sulphur (on the left) is passion and desire inciting to action, and thus to self-consciousness; mercury (on top) is wisdom, i.e. superconsciousness; and water as dissolution refers to "man as the dissolver of the phantoms of illusion (Tarot Fundamentals, Chapter 24, p. 6)).

For both Waite and Case, the Wheel shows, on its spokes, the symbols for the three basic concepts in alchemy: salt,

sulphur, mercury, to which the Golden Dawn added water, the principle of

dissolution, to make four. According to Case, salt (on the left) corresponds to inertia, the dominant quality of subconsciousness; sulphur (on the left) is passion and desire inciting to action, and thus to self-consciousness; mercury (on top) is wisdom, i.e. superconsciousness; and water as dissolution refers to "man as the dissolver of the phantoms of illusion (Tarot Fundamentals, Chapter 24, p. 6)).

Waite, followed by Case, changed Levi's devilish "Typhon" to a serpent. According to Case, the waviness of the serpent indicates vibration: "It stands for the descent of the Serpent Power, Fohat, into the field of physical manifestation. Thus it represents the involution of Light into Form" (lesson 24, p. 9)

As for the Hermanubis, Case says, it represents the "average development of the human personality." That it has the head of a jackal indicates that "humanity as a whole has not evolved beyond the intellectual level" (Ibid.) But that its ears are higher than the middle of the wheel indicates that "through interior hearing (intuition- Key 5) humanity is beginning to have knowledge of the cycle of evolution through which we are destined to rise" (Ibid.)

The Sphinx indicates the perfection of that process. That the Sphinx has a woman's head and breasts, combined with the body of a male lion, signifies that she is "the union of male and female powers, the perfect blending of forces which at lower levels of perception appear to be opposed" (lesson 24, p. 10). What makes the lion-body male rather than female he does not say.

For Case the movement upwards is a positive development, evolution. The movement downward on the other side is "involution," a term he does not define, but in esoteric usage refers to the descent of spirit into matter and so into more and more imperfect forms, the opposite of evolution. In the 15th-16th century, the positive part was the movement downward, if one has learned the vanity of worldly things. Perhaps when Case says that the serpent represents "light" and "the descent of the serpent-power, Fohat, into the field of physical manifestation," he is saying something similar (lesson 24, p. 9). In that case, both sides of the Wheel are positive, in different ways: energy and intellect on one side, spirit and understanding on the other.

Case also pays attention to what is inside the Wheel:

Its center, or pivot, is the archetypal world; the inner circle is the creative world, the middle circle the formative world, and the outer circle the material world. (The Tarot: a Key to the Wisdom of the Ages, p. 121.)

In the same work, Case offers a concise summary at the end of the chapter:

Psychologically, this Tarot Key refers to the law of periodicity in mental activity, whereby mental states have a tendency to recur in definite rhythms. It is the law, also, of the involution of undifferentiated conscious energy, and its evolution through a series of personalized forms of itself. Finally, the Wheel of Fortune is the Tarot symbol of the law of cause and consequence which enables us to be certain of reaping what we have sown. (Ibid., p. 123)

4. Jungian Perspectives

Sallie Nichols subtitles her chapter on the Wheel as "Help!" Given that all the figures around the TdM card are animals, what she sees is endlessly repeating cycles of instinctual life, the positive energy of Anubis sometimes ascending but sometimes descending, and the same for the negative energy of Typhon. She writes (Jung and Tarot, 1980, p. 180, in archive.org):

It is the task of all human beings, striving for consciousness, to liberate animal energies previously caught in the repetitive instinctual round, so that this libido can be used in a more conscious way.

How to break the cycle, get off the wheel, or turn circles into spirals, i.e. achieve something new and better in successive rounds?

But first, who are they? She observes that we are confronted here with "our two friends, the opposites" (p. 180). She is comparing the one going up and the animal going down with the two horses of the Chariot card and the two pans of Justice. Now, she says, we have the yang energy to dominate and organize on one side and the yin energy to receive and contain on the other.

I assume the first is on the right and the second on the left. I am not sure how "receptive" the figure on the left is, as he falls from grace; but he certainly is not active. In any case, that is only two of the figures.

In the early Wheel images, there are four figures. Jung in the essay, "The Stages of Life," has the same. His are childhood, then young adulthood, late adulthood, and extreme old age. The definitions of the two middle stages only emerge when there is a problem of the transition from the previous one. In the period of youth, he says:

Something in us wishes to remain a child, to be unconscious or, at most conscious only of the ego; to reject everything strange, or else subject it to our will; to do nothing or else indulge our own craving for pleasure or power. ("Stages of Life," Collected Works, Vol. 8, para. 764, in archive.org.)

Yet after childhood there are social demands, the need for a livelihood and to be useful to others. If we take childhood dreams into this arena without adequate preparation, the result can be disastrous, yet not fatal. One may learn fortitude, temperance, and justice. In any case there is a narrowing of the personality so as to "achieve the attainable"; for some, it is a career, for others, raising a family, or both at once. This works for a while, indeed, for 20 or 30 years. Then the children are grown, and work gets old; there come nervous breakdowns, depressions, feelings of meaninglessness. Moreover in many cases one just isn't up to the same level of achievement as formerly. Things change into their opposite, even though there is the same reluctance to do so. Even the body goes through changes (CW vol. 8, pp. 397-8, para. 780, 781):

Especially among southern races one can observe that older women develop deep, rough voices, incipient moustaches, rather hard features and other masculine traits. On the other hand the masculine physique is toned down by feminine features, such as adiposity and softer facial expressions. . . .

. . . There is an interesting report in the ethnological literature about an Indian warrior chief to whom in middle life the Great Spirit appeared in a dream. The spirit announced to him that from then on he must sit among the women and children, wear women's clothes, and eat the food of women. He obeyed the dream without suffering a loss of prestige. This vision is a true expression of the psychic revolution of life's noon, of the beginning of life's decline. Man's values, and even his body, do tend to change into their opposites.

In modern society, there is a parallel (p. 398, para., 783).

How often it happens that a man of forty-five or fifty winds up his business, and the wife then dons the trousers and opens a little shop where he perhaps performs the duties of a handyman. There are many women who only awaken to social responsibility and to social consciousness after their fortieth year. In modern business life, especially in America, nervous breakdowns in the forties are a very common occurrence. If one examines the victims one finds that what has broken down is the masculine style of life which held the field up to now, and that what is left over is an effeminate man. Contrariwise, one can observe women in these selfsame business spheres who have developed in the second half of life an uncommonly masculine tough-mindedness which thrusts the feelings and the heart aside.

These are two stages of life, or more precisely, two stages of adulthood, one before and one after the midpoint, i.e. around 40 years of age, plus or minus; in the latter, aspects of life formerly shunted aside become a new source of meaning. After that there is a fourth stage, "extreme old age," the criterion for which is the same as the first: dependency on others and a large share of life lived in unconsciousness. As he concludes his essay (p. 403, para. 795):

Childhood and extreme old age are, of course, utterly different, and yet they have one thing in common: submersion in unconscious psychic happenings. Since the mind of a child grows out of the unconscious its psychic processes, though not easily accessible, are not as difficult to discern as those of a very old person who is sinking again into the unconscious, and who progressively vanishes within it.So that is one way of seeing the Wheel of Fortune, as the Wheel of Life and, in Jung's main metaphor here, the arc of the sun as it crosses the sky. In this case there is the top half of the wheel, which divides into two parts, and the bottom half, also in two parts. Going up is the road of achievement, what Nichols calls "yang" urge to dominate. Going down is the road of "yin" receptivity, not necessarily of a fall in position in society, but at least of internal turmoil or depression and the need to find new meaning in life. In former eras there were schools for both, with monasteries as especially adapted to the latter. Nowadays we still have such places, but there are also Zen retreats, ashrams, and Jungian institutes and other such schools aimed more toward midlife issues than those of the earlier period. He no longer looks to the figure at the top for approval. Instead, assuming there is water at the bottom, he is learning to swim underwater, taking occasional breaths at the surface.

In that way the animal going up is human in his ability to climb, but an animal in his head, like a dog learning tricks. The one going down has lost the ability, or at least the will, to climb, but is human in his head. Jung's first and fourth stages are just the extreme low ends of the two sides. In the older tarots there would have been an old man in a night-shirt.

Wha t then of the top? I turn again to Sallie Nichols in Jung and Tarot. Looking at the late "Marseille" version (Chosson as opposed to Noblet) and Waite's she identifies it as a sphinx, and specifically the female Greek version; I offer at right a 530 b.c.e. statue now in Metropolitan Museum, New York. Nichols says that it "represents a negative mother principle" (p. 181). This much is consistent with Jung, who says in Symbols of Transformation:

t then of the top? I turn again to Sallie Nichols in Jung and Tarot. Looking at the late "Marseille" version (Chosson as opposed to Noblet) and Waite's she identifies it as a sphinx, and specifically the female Greek version; I offer at right a 530 b.c.e. statue now in Metropolitan Museum, New York. Nichols says that it "represents a negative mother principle" (p. 181). This much is consistent with Jung, who says in Symbols of Transformation:

it frequently happens that if the attitude toward the parents is too affectionate and too dependent, it is compensated for in dreams by frightening animals, who represent the parents just as much as the helpful animals did. The Sphinx in the Oedipus legend is a fear animal of this kind and shows clear traces of a mother-derivative. (CW vol. 5, p. 181, para. 264, in archive.org)

As for Oedipus's encounter with the Sphinx in the story, Jung's view is that the tragedy could have been avoided if only he (Ibid., pp. 181-2, para. 264):

had been sufficiently intimidated by the frightening appearance of the "terrible" or "devouring" mother whom the Sphinx personified. He was far from the philosophical wonderment of Faust" "The Mothers, the Mothers! It has a wondrous sound." Little did he know that the riddle of the Sphinx cannot be solved by wit alone. .

But of course then he would have missed his chance to be king, the hero's reward, for answering such an "chidishly simple" riddle, as Jung calls it (para. 264, p. 181).

In the version of the story that we know from Sophocles' play, Oedipus grows up believing that the couple who raised him, the king and queen of Corinth, are his real parents. (Since they had been childless themselves, they must have showered the foundling delivered to them with much care and attention.) He learns from the oracle of Apollo that he will kill his father and marry his mother. To escape that fate, he runs away. First he kills an old man who won't yield to him at a crossroads, and then he comes to Thebes, which has lost its king. If he answers the Sphinx's riddle and marries the queen, he will be king. If he doesn't guess right, he dies, like many before him. The riddle is "What has one one name, but walks on four legs, two legs, and three legs?" Oedipus answers, "Man, crawling as a child, then standing, then with the help of a cane." (These happen to be three of Jung's four stages. What it leaves out is the reversal of direction and the consequent division of adulthood into two parts.)

So the heroic Oedipus kills the sphinx and marries the queen. Everything goes well for a while, and then there is a terrible plague that won't go away. The oracle of Apollo says to find out who killed the previous king, Laius. Heroically investigating, he finds that the man he killed was not only Laius but his real father, and the queen his real mother. The plague lifts, the queen kills herself, and he puts out his eyes to await the oracle's verdict. In the continuation, Oedipus at Colonus, he is a blind wanderer accepted nowhere, yet deemed a prophet. (He is in the position of the man at the bottom of the Wheel in the early versions, Nichols points out. He also has something in common with the Hermit.)

We can see Oedipus's life on the Wheel of Waite and Case. In killing his father and confronting the Sphinx, he is in the position of Hermanubis, whom Case associates with fire. The Sphinx, with its wings, is air, engaging Oedipus's intellect. The serpent of wisdom is his watery stage of shame and tears. The stage of earth is neither in the play nor the later cards: it is the man sitting in his nightshirt at the bottom of the earliest cards, fully human, who at the end of Oedipus at Colonus enters the cave that will be his tomb.

Unlike Jung, Oedipus

only knew about three stages of life, childhood, adulthood, old age. So the second part of adulthood, before extreme old age, comes as a surprise.

Citing Jung's student Marie-Louise von Franz in The Problem of the Puer Aeternis (pp. 169-170 in the 3rd edition on archive.org), Nichols says (p. 181):

Although Oedipus succeeded in solving the riddle propounded by the sphinx, he did not thereby redeem his instinctual nature from her power. On the contrary, he still remained in the grasp of cruel fate, as helpless as any animal revolving on the wheel of instinctually predestined behavior.

He is in the grip of his mother-complex, von Franz says, with Nichols concurring. The problem is that he tried to "think things through" on an intellectual plane without reckoning with the demands of the unconscious. Nichols says (p. 183):

As von Franz reminds us, it is a familiar plot of the unconscious to distract the hero (human consciousness striving toward wholeness) by proposing philosophical questions at the very moment when he most needs to confront the demands of his instinctual nature.

The Sphinx is a kind of double-edged sword (p. 185).

On the one hand, she presents us with a heroic task, the challenge of human beingness, daring us to find meaning in a system seemingly propelled by mere animal energy. On the other hand, she deliberately distracts us with her conundrums, deflecting us from our quest and sapping our strength with her insatiable demands.

In the end, Oedipus learns that he cannot defeat fate. Nichols concludes (p. 185):

If we cannot rise above our fate, we must find some other way to deal with the sphinx and her Wheel.What is the solution? Near the end of the chapter she returns to Oedipus and the prophecy about killing his father and marrying his mother (p. 198):

If Oedipus had considered the soothsayer's prophecy symbolically rather than literally, and if he had examined his inner terrain rather than setting forth to change his outer geography, he might have avoided the fate which was prophesied at both the literal and the symbolic levels. For example, he might have taken "killing his father" as a warning to control his impulsive, hot-headed actions, his quick murderous temper, and the overwhelming pride of youth, which demanded the right of way in any encounter and turned against all established values. He might have explored his tendency to "marry his mother" as symbolizing an infantile need for overprotective mothering. A modern Oedipus, faced with such dire premonitions, might have sought professional help of some kind, thus perhaps avoiding murder and incest both, symbolically and literally.

This solution is much like Levi's, only psychologically expressed. There may be more, as for Jung himself there was a certain numinosity - an experience of awe before the incomprehensible - appropriate to the sphinx. There is also a certain way in which the legend is more horrific than any of them have taken into consideration. Oedipus suffers a terrible trauma in infancy. Just because he doesn't remember it, doesn't mean it doesn't affect him. Here is the relevant dialog (http://classics.mit.edu/Sophocles/oedipus.pl.txt):

JOCASTA. As for the child, it was but three days old,

When Laius, its ankles pierced and pinned

Together, gave it to be cast away

By others on the trackless mountain side.

That particular treatment does not happen literally, these days, but it happens enough, in varying degrees up to and including death. No wonder Oedipus is defensive and quick to anger, regarding all men as potential enemies. So yes, the prediction is symbolic. But there is also the context of personal history. This involves paying attention to what one is blind to, precisely because of traumas: that the man he wants to attack is old enough to be his father, that his ankles still bear scars of something, he knows not what.

The name "Oedipus" means "swollen foot" and indicates the ankle-wound that he carried ever after, as implied by a comment made by the man who brought the child to his foster parents, the childless king and queen of Corinth:

MESSENGER I loosed the pin that riveted thy feet.

OEDIPUS Yes, from my cradle that dread brand I bore.

MESSENGER Whence thou deriv'st the name that still is thine

Dreams and repetitive behavior-patterns, are like those scars, overlooked by consciousness because of where they might lead. Examining dreams, hypnagogic visions, and others' reports of one's behavior patterns are the equivalent of examining those scars.

Then there is the issue of the "over-protective mother." That is only part of the story. Here we have to remember that Oedipus's mother/wife Jocasta omitted one thing in her later account to Oedipus, namely who it was who gave the child to a servant to "make away with it." The servant, now a herdsman, later testifies:

HERDSMAN Know then the child was by repute his own,

But she within, thy consort best could tell.

OEDIPUS What! she, she gave it thee?

HERDSMAN 'Tis so, my king.

OEDIPUS With what intent?

HERDSMAN To make away with it.

OEDIPUS What, she its mother.

HERDSMAN Fearing a dread weird.

OEDIPUS What weird?

HERDSMAN 'Twas told that he should slay his sire.

"Weird" evidently refers to the prophecy. I quote this part because Nichols blames only the father, when it would seem that both were trying to kill him. It is no wonder that Oedipus did not ask questions when a woman old enough to be his mother falls into his lap, so to speak: it was too painful. He had an unconscious fear of abandonment and a yearning for protection that, in his situation (that of a hero defending against these feelings) needed to be felt for what it was in a safe place, like the protective womb of a therapist's office.

I think also it is important to recognize the role of Apollo in the story, which tends to be ignored. As the god of prophecy, it is his oracle that starts things out and also repeats when Oedipus is older. Apollo is also that god of plague, and it is he who sets Oedipus to find out about his origins. He is the god of sickness, healing, and light. It would seem the Apollo is an initiation-master here, and the one who drives Oedipus to search for meaning after the Sphinx's proves illusory.

Nichols calls attention to the Wheel's place in the sequence of 22 cards. As Jung reminds us, life for medieval theology was a process of descent into matter and then freeing oneself from matter again, the descensus and ascensus. The first part of this process is in the cards before the Wheel:

In psychological terms, the ego is born, develops strength, begins to free itself from dependence on its parental archetypes, and establishes itself in the world. (p. 190)

The remaining cards then have to do with "the disentanglement of spirit from matter":

In psychological terms, the remaining Trumps represent the second stage of life, where the ego's energies, having conquered the outer world, turn inward toward spiritual development. (Ibid.)

The more one makes one's "mark" in the world, the further down one has fallen, until one finds oneself in the depths of matter, after which come the trials of the Wheel and the journey's reversal. In that way the soul's progress through the 21 steps of the sequence mirrors that down-up progression, first descending from the One (the ego, or what Case calls self-consciousness), then reversing at the Ten, precisely at the card of the Wheel, orienting toward the heavens and traversing them.

In the same way, our theorists - at least Papus and Wirth - attach sefiroth on the Tree of Life to the cards by their number, at least on the way down: Kether with the Magician, Hochmah with the High Priestess, and so on, with Malkuth at the Wheel of Fortune. After that, they stop. Case does something similar, but not as consistently. Interestingly, in his case, he makes a few assignments that correspond to the places they would get going up: Yesod, for the Hanged Man, second from the bottom if Strength is first on the way up. He also has Kether for the World. The Golden Dawn, on the other hand, in assigning cards to paths, assignments that Case also endorses, simply goes in one direction, down the Tree.

Nichols adds that the places on the wheel are not restricted to any particular age ranges (p. 191):

The Tarot Wheel represents a turning point that can take place at any age - and it will turn for us all many times.In this connection there is the phenomenon of the repeating dream. It is like the ringing of a telephone. Until you answer it, it will keep on ringing, i.e. repeating. She quotes Jung in Psychology and Alchemy (CW vol. 12, pp. 28-9, para. 34, in archive.org):

The way to the goal seems chaotic and interminable at first, and only gradually do the signs increase that it is leading anywhere. The way is not straight but appears to go round in circles. More accurate knowledge has proved it to go in spirals: the dream-motifs always return after certain intervals to definite forms, whose characteristic it is to define a centre.

Jung in that place elaborates on this point (paras. 34-35):

And as a matter of fact the whole process revolves about a central point or some arrangement round a centre, which may in certain circumstances appear even in the initial dreams. As manifestations of unconscious processes the dreams rotate or circumambulate round the centre, drawing closer to it as the amplifications increase in distinctness and in scope. . . . . The centre or goal thus signifies salvation in the proper sense of the word. The justification for such a terminology comes from the dreams themselves, for these contain so many references to religious phenomena that I was able to use some of them as the subject of my book Psychology and Religion.

The idea of the center as "salvation" fits with Case's notion that the center of the Wheel is the archetypal level, going out through the "four worlds" of Kabbalah to the material world of the senses at the circumference. But how to find the center when one is on the circumference?

The way toward the center is by "amplifications." This doesn't come by reasoning, but by exercise of the imagination, Nichols says. There are various questions one can ask of it and imagine a response. One can also try to paint it, and then reflect on what one has spontaneously produced in terms of one's life. On can also spread out the tarot trumps and try to find cards that relate specifically to the content of what one has produced. Another technique is to take a problem of personal concern and turn it into a story with a protagonist other than oneself, and then imagine the story continuing on, omitting nothing that occurs to one, however foolish it may appear.

It is also a question of living one's life in harmony with the "primordial images," those that are older than human history. Jung says in "Stages of Life": (CW vol. 8, pp. 402-3, para. 793):

It is only possible to live the fullest life when we are in harmony with these symbols; wisdom is a return to them. .

These include the idea of something beyond this life (Ibid., p. 403):

One of these primordial thoughts is the idea of life after death. Science and these primordial images are incommensurables. They are irrational data, a priori conditions of the imagination which are simply there, and whose purpose and justification science can only investigate a posteriori.

I am skeptical about the idea of personal survival after death being primordial. What is primordial is "magical thinking", including prophecy, to which of course science would deny any validity. Yet is true that in the third and fourth quarters of life. the imagination does attach more importance to the issues of what is beyond ego consciousness and what is beyond this life, and the principles governing this attitude can indeed be investigated, if not the truth of what the imagination brings.

From a Jungian perspective, the Wheel gives us the first picture in the tarot sequence of the Self, as the totality of life. The ego, however, is not yet connected with the center, which in this interpretation is not fickle Fortuna but the archetypal center of the whole personality. To the extent that the whole, which includes the organism itself with its defects, is not only beyond consciousness but beyond time and space altogether, as a psychoid reality of which consciousness and materiality are two aspects, including also the personality's link to Providence, that which sees the whole and acts for the sake of the whole. It leads to fortuitous coincidences - "synchronicities" - that give an unexpected meaningfulness to one's actions.

A psychological version of the experience of Providence is in Shakespeare in Hamlet (whether Hamlet is another Oedipus I leave to others). Here is the relevant part of the plot. Hamlet's uncle Claudius kills Hamlet's father, King of Denmark. The need for revenge, but as well for some kind of proof of Claudius's guilt, plus his mother's marriage to the suspected murderer, drives Hamlet half-mad, not to mention toward a certain indulgence in philosophical games (to use von Franz's phrase). A series of misadventures leads Claudius to decide that to protect himself Hamlet must be killed, secretly and away from those who love him. Here, at least in Hamlet's eyes, Providence enters in, giving Hamlet just the right tools he needs to fight back, namely his father's seal, which he has on the ring he is wearing, and the ability to write in a reasonable facsimile of Claudius's handwriting, whereby he can alter the hanging to be of his traveling companions, whom he knows report back to Claudius, rather than himself. As Hamlet tells his friend Horatio while relating these events (5.2.10-11):

Our indiscretion sometimes serves us well,

When our deep plots do pall: and that should teach us

There's a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will.

He is the tool of Providence and accepts whatever she will make of him, including the sacrifice of his life, as he says later, rejecting Horatio's feelings of foreboding about a fencing match Claudius invites Hamlet to engage in (5.2.201-5):

We defy augury. There's a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not know, yet it will come - the readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is't to leave betimes, let be.

"Fall of a sparrow" is a reference to Matthew 10:29:

Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? and one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father. (King James Version)This verse was considered an intimation of the crucifixion. In the language of Karma, Case might say that because of his rash act of killing Polonius and thereby revealing his danger to Claudius, his Karma leads to his death; but because of his devotion to justice, he has the Karma of being able to finally kill Claudius. In any event, he is in the hands of Providence.

5. Conclusion

The Wheel of Fortune has made many turns in the history of the tarot. It started out as an allegory of the vanity of earthly desires, then an allegory of prudence and temperance (self-control) in the face of an uncertain future. Then Fortune became the figure on top of the Wheel, royalty dispensing favors and casting down unpredictably. That royalty became a sphinx, either to Egyptianize royalty or to suggest that the sphinx was the riddle of existence, in particular its higher meaning, with those who fail to unravel it descending into the chaos. Levi's new design makes the latter more explicit, becoming an allegory of good and evil, with the good striving upwards and the evil plunging downward, somewhat the reverse of the original idea. With Waite and Case, the two sides become more ambiguous, as the serpent is not only the tempter in the Garden but also a symbol of prudence or wisdom, and the red of the Anubis-figure is both the vitality of life and a fire of destruction. A Jungian perspective is in many ways similar to Case's, except for extending the ambiguity to the top figure as well as to the figures on each side.

No comments:

Post a Comment