This post last modified November, 2022. Footnotes accessible by clicking on the colored numbers [in square brackets].

1. The name of the card.

Today's students of the tarot may recognize the Rider-Waite-Smith imagery,

designed for use in divination, as the “classic” tarot. In fact the imagery of

the tarot, of which the earliest known mention is in 1440 Florence, Italy, [1] has had a variety of manifestations over the centuries. For centuries the

primary, most clearly documented, and possibly only use of the tarot deck was in

a trick-taking game, where the cards unique to the tarot, except for the Fool,

formed a fifth suit that could beat any card of the other four.[2] Although their order varied from city to city, the Magician was always the

lowest card in the suit so defined; the Fool was lower, but since it could be

taken by any of the cards of the four suits, it not technically part of the

suit that "trumps" the other four. The Magician's earliest surviving

example is that in a Milanese deck probably of the 1450s, for which see the

beginning of the next section.[3] There, as almost always on the card, we see a gaudily dressed man in front

of a table with various objects on it. The imagery of the card will be

discussed later; but first there is the question of its title.

The title first recorded, in an Italian list of the late 15th century, was El

Bagatella.[4]

In the etymological dictionaries, the word is said to be of unclear origin.

It is possibly from bagatte, meaning “seller of small things.” There is

also bagattino, a small coin, and the Latin bacca, small round

thing. The card had other early titles, the aforementioned bagattino and

also bagatello, both documented later than bagatella, and both,

unlike Bagatella, with clearly masculine endings.Although not

mentioned in the dictionaries, there was also bacchetta, meaning “little

stick” (in French, baguette), also the word for a magician’s wand.[5] And besides El Bagatella, there

was La Bagatella, meaning "small thing" or “trifle.” With that

association, the man on the card would differ from a Mago, who was

considered to be in league with supernatural powers. The Bagatella merely

creates illusions.

This term Bagatella applied to a person is already found in the fourteenth century. Lodovico Muratori, in his 18th century etymological study of the term, documents an example of ca. 1389:

Of which was the sower of discord Servideus, first chorister of this Church, called by the last name Bagatella because of his shady and childish quibbles, or because he knew the art of Bagattandi.[6]

But what is this “art of Bagattandi”? To make much

out of little? To deceive? To be like a professional illusionist? All are

possible.

Muratori also cites a poem thought then to date from c. 1300. As found in a book printed in 1617, it reads:

Lassovi la fortuna fella /Travagliar qual Bagattella:

Quanto più si mostra bella, /Come anguilla squizza via.

(I leave to you wicked fortune/ Who acts like a Bagattella:

Whenever she seems most beautiful,/ She slips away like an eel.)

The translation is by Marco Ponzi on Tarot history Forum.[7] Here the Bagatella, like the goddess Fortune to whom he is being compared, would seem to be an illusionist and a deceiver.

According to linguist Alessandro Parenti,[8] these lines can also be read in another way:

I leave traitorous fate/ agitating itself like a puppet:

The more it flatters [one] / the more it squirms away.

For Bagatella, Parenti found the meaning "marionette, puppet" in some old dictionaries. Either way, the Bagatella is a deceiver, although the second is less applicable to our card, which never shows a puppet.

The earliest version of the poem, however, is in a Florentine manuscript toward the end of the 15th century, recording a text that it says dates to 1415 Padua. There it starts[9] :

Lasso la fortuna bella, / Travagliar sua bagatella . . .

(I leave beautiful fortune / To work its bagatella. . .)

etc., where again either "puppet" or "trick" will fit.

At some point the tarocchi, as the game was called in

Italian, spread to France, first recorded there in 1505 Avignon, with the

spelling taraux.[10]

In French the figure on the card was called the Bateleur, earlier Basteleur,

etymologically connected with the French word for “stick,” bâton,

earlier baston, and baastel, the instrument of an escamoteur,

a conjurer or sleight of hand artist.[11]

Historically in France, a bateleur was the quick-handed and fast-talking

entertainer who attracted crowds so that he or someone else, as a charlatan,

i.e. a non-licensed prescriber, or “empiric,” could sell remedies for which he

claimed empirical validity even if he didn’t know why they worked, as opposed

to treatments based on theory that the medical establishment endorsed.

Naturally such sellers were considered quacks, and doubtless some were. A 16th

century engraving of the Piazza San Marco in Venice[12] shows them at work on the raised platforms that gave them the name saltimbanco,

platform-mounter. Another word for them was Cantambanco,

platform-singer. For Muratori, Bagatelle, besides being “trifles,” were

the “tricks and games” of the cantambanchi. [13]

Saltimbanco came into English as "mountebank", a term

sometimes used by tarot historians to describe the tarot figure[14]. Of an unsavory reputation, in Shakespeare such people could be a source

of lethal drugs. Laertes, Hamlet’s foe, relates: “I bought an unction of a

mountebank,” such that the merest cut inserting it would bring death. The word

occurs again in Comedy of Errors:

They brought one Pinch, a hungry,

lean-faced villain,

A mere anatomy [skeleton], a mountebank,

A threadbare juggler, and a fortune-teller...

“Juggle” then meant “entertain with jesting, tricks, etc.”[15]

2. The Imagery of the traditional card

In the earliest preserved Magician card, of 1450s Milan, at left below,[16] he has objects on his table similar to the four Italian suit signs: the wand suggests Staves, in Italian Bastoni; the round objects, perhaps shells, Coins (Denari); the knives, Swords (Spade); and the cups, Cups (Coppe). These four types of object continue in the French tarot decks of the so-called "Tarot de Marseille" (TdM), for example, in the middle below, in the card of Chosson, a card maker in Marseille active starting in c. 1735 but perhaps from a mold done in 1672, the date on the 2 of Coins. The four types of objects are made unquestionably clear in the 19th and 20th centuries, most famously in the Rider-Waite-Smith card, at right.[17]

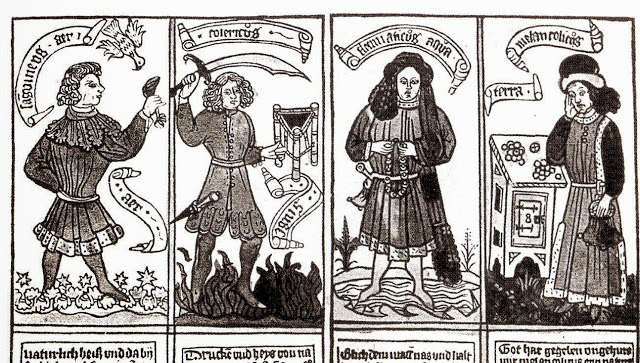

Even in the 15th century, as seen in the illustration below, such objects were used to symbolize the four elements - earth, water, air, and fire - that made up the world and so, symbolically, the conditions in which we find ourselves at birth and after.[18]

In this way, the card suggests metaphors with multiple meanings. On the one hand, if the four types of objects are the four suits, the Magician could be the dealer in a game of cards. Each player receives a certain combination of cards that represent his lot in the life of that hand. So the suit of Coins could correspond to money, as in the illustration at left below. Swords could be the weapon wielded in the second image. They are also the "melancholy humor" and "choleric humor" of medieval "humor" theory. As for Batons, beside the wooden perch for the falcon shown on the first image in the illustrations, they suggest the fertility of spring and youth (signified by the green club of the Ace or the gloves and sleeves of the courts, as in the Visconti-Sforza Queen and Page, at left,[19] and the related emotion of vigor and enthusiasm, the "phlegmatic" humor. Cups associate to water or wine, which then associate to the water of baptism and the wine of the Eucharist; similarly, in the illustration water is associated, without explanation, with the Catholic Rosary and the "phlegmatic" humor. The suits are then four types of capital, in various senses, for the players to use as they will. And the dealer is a kind of little god giving each player his or her individual sets of choices or opportunities in life.

To the extent that the four types of objects also symbolize the four elements, the one who manipulates them is a kind of creator-god, creating new things out of more basic elements. It was quite mysterious how something of the earth could be dissolved (water), burned (fire), turned to vapor (air), and be something different when, in sealed containers, the process was reversed. Sometimes the result was healing medicine, other times lethal poison, occasionally some metal. It was called alchemy, a precursor of modern chemistry. Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, was in the 14th century typically represented at a table like the Bagatella’s, with various substances on it and in jars behind it (containing herbs?), above right. Later the alchemist would be depicted similarly, as below right.[20]

The metaphor easily extends into a spiritual dimension, in

more ways than one. The Bagatella at his table, with his round, wafer-like

objects and cups, is reminiscent of a priest conducting the Eucharist. The

first known Bagatella is not young, and he has baggy eyes and a weary look,

like a priest whose admonitions people ignore (see below). At one end of his

table is a mysterious object, perhaps a straw hat, out of which he may later

pull something, or perhaps it is to cover something, in the way that a cloth

covered the Eucharistic cup. If the other objects are the four elements, then

perhaps the hat or cloth covers a magical fifth element, the so-called

quintessence; for the priest, it was the stuff of eternal life, passing from

beyond into the bread and wine. In the French tarot decks of the 17th-18th

centuries, the covering is still there, but it is a purse (in the first image

in this post compare left with center). The 20th-century

tarots (e.g., Waite's) removed all trace of this magical symbol.

A religious metaphor is suggested not only by the table and the Bagatella’s

face, but also by that face in relation to other work by the artist of the

first known card, Bonifacio Bembo. In his art, similar faces are reserved for

the figure of Jesus,[21]

who besides being a healer and humble stepson of a carpenter was declared in

the Gospel of John to be the one by whom “all things were made” (Jn 1:3).

Below, compare the face of the Bembo Magician with of two of his depictions of

Jesus done in the same period, one a Coronation of the Virgin (at left below),

the other an Ascension.

In the game that was played with the cards, although he was the lowest trump, the player who had him at the end of the hand stood to get many points. In some places, moreover, there were extra points for winning the last trick with this card. It was an opportunity for allegory: the least is the highest, at the end of the game.

Other allegories were made. Hugh Latimer, a sometime Bishop in 1529 England, later martyr of the nascent Church of England, preached a pair of “sermons on the cards.” He compared life to a game called “triumph.” This game in England was played with the ordinary deck of four suits, of which one was declared “trumps.” Latimer preached that Jesus was the dealer, that hearts were trumps, and what was needed was to pick up the cards of His commandments with one’s trump - one’s heart - that all might be winners, including Jesus.[22]

This was with ordinary cards, of which one was randomly chosen to be trumps. The tarot, originally called “trionfi” or “triumphe,” had a permanent trump suit; the word “trump” is merely a variation on these Italian words.

This fifth suit was seen by some, including two Italian authors writing around 1565, as allegories pertaining to the conduct of life. For Francesco Piscina, he was "l'Hoste" - the Innkeeper - of the "inn of the fool." Whereas formerly people would go to the "hosteria dello Specchio" - Inn of the Mirror, meaning a place for self-reflection - now they went to the inn whose sign in front said it was "quella dil Matto," that of the Fool, and people came to enjoy themselves.[23] For whatever reason, Sicilian cards to this day show a scene on the card that suggests an innkeeper (at right), even if its actual title is "the young men." Moreover, the jurist Andrea Alciati in 1544 even called the card "Caupo," meaning "Innkeeper," in his listing of the trumps.[24]For the other 16th century author, writing anonymously, the Fool card, probably thought of as having the number 0, it was also next to the "Bagattello," with a moral that depended on his having a different profession[25] (my explanatory comments in brackets):

(He [the deck's designer] placed the Bagat [Bagatello] next to him [the Fool]: because, like those that play with swift hands, making one thing like another one, causing wonder and a vain amusement, in the same way the world attracts the others with images of beauty and delight, promising happiness at the end of trouble. As a juggler [prestigiatore, literally quick-hands artist], it contains nothing, neither permanent nor durable, and leads to a miserable end, under the false appearance of good.

For Anonymous, in other words, the Magician is nothing but

an allegory for the deceptiveness of the world. The English word 'juggler"

is sometimes used to translate the Italian "prestigiatore"; but it is

in only an obsolete sense that this translation works: he is obviously not

someone who keeps objects in motion in the air.

Similar to Piscina's comparison of the tarot sequence to an inn, a frontispiece

by Hans Holbein in 1523 features a large enclosure in which we see allegorical

representations of various virtues and vices and people attending to one or

another.[26]

It reappeared in slightly different form as the frontispiece to various works

published in Switzerland. To that extent it is like Piscina's image of an inn

with various entertainments. At the entrance are naked infants, souls waiting

to enter life. Before they go in they are greeted by a figure depicted with a

large hat and a stick in his one hand. not dissimilar to some versions of the

Magician card around that time, such as the Catelin Geoffroy of 1557 Lyon (23).[27]

Below I give Holbein's design, a 1532 variant, and the Geoffroy card.

The work which the frontispiece illustrates is the so-called Tabula Cebetis, Tablet of Cebes, a Platonic-style dialogue of around the first-century c.e. printed at the end of the 15th century and popular with teachers of Greek. About this scene it says:[28]

First you must know that the name of this whole place is the Life. This innumerable multitude surging in front of the Gate are they about to enter into life. The Old Man who holds a scroll and with the other is pointing out something is the Good Genius. To those who are entering is he setting forth what they should do when they shall have entered; and he is pointing out to them which WAY they shall have to walk in if they propose to be saved in 'the Life.'

At the gate there is also a woman who has the souls drink from a cup she is holding; her name is Delusion ("Suadela," Deceit, in the engravings), and her drink is that of "Error and Ignorance."

Unfortunately, all who enter must take this drink. Both

references are to Platonic allegory. Plato taught that archetypes of the Good,

the True, the Beautiful, and other perfections were implanted in our minds

before birth: the "good genius" is then the agent of such

implantation. He also taught that souls were required to drink the "cup of

forgetfulness", Lethe, before entering a new incarnation.

In this allegory the "good genius" who implants in us the knowledge

of how to live has some of the features of the tarot Magician, both in his

appearance and in his role as initiator of the tarot sequence as a repository

of wisdom, something each of us has implanted in us from before birth. However,

as a sleight-of-hand artist the Magician also has the qualities of the lady

Delusion who obscures this knowledge.

The 15th-16th century cards after the first known, the Visconti-Sforza, replace

the wide-brimmed hat with one less flamboyant. Besides the Catelin Geoffroy,

shown above, some examples are the d'Este, the "Dick Sheet" of

Ferrara or Venice, and the Cary Sheet of Milan or France (below, left to right). In other cases, the

man at the table acquired the tassels normally associated with the Fool, as in

the Rosenwald sheet, second from left. While there is some resemblance between

the tassels of the professional entertainer on the Rosenwald and a wide-brimmed

hat, the two are still fairly different. The four types of objects have also

been reduced to two or three, (except in the Cary Sheet): in the d'Este, it is the

famous "cups and balls" game. It is hard to tell what is being

depicted in the other two.

Yet somehow the wide-brimmed hat returned in 17th century France, where in the "Tarot of Marseille" style it achieved dominance in the 18th century. The earliest example of this style is the card of Jean Noblet in 1660s Paris, shown at right below. Why this comeback? No one knows, but it is possible to make reasonable speculations, i.e. ones consistent with the interests and knowledge of the time, such that it would be easy to give the hat a certain interpretation in meditation or as part of a discussion among friends.

Educated people in 17th and 18th century France had an inexhaustible

fascination for ancient Egypt. That some people in the 1780s Paris declared the

tarot to be of Egyptian origin was only one expression of that interest. That

not much was known only increased the value of what was known. Besides sketches

made by commercial travelers with antiquarian interests, there was the

so-called "Bembine Tablet,"[29]

which had been acquired by Pietro Bembo (no relation to the card painters) in

1507 and of which sketches were made and avidly passed around. Court de Gébelin

refers to it in his famous 1781 article on the tarot's Egyptian origin. What is

of interest for this card is the strange horizontal horns that correspond to

the TdM Magician's broad-brimmed hat. All the priests have them, and so does a

small ram.

In this picture, it is the ram that tells us what divinity is being served, and

the priests show whom they serve through the visual relationship between their

horns and the ram's. The significance of the ram in Egypt had been explained by

the Greek historian Herodotus: it is sacred to the high god Amon, because the

god himself put on the head of a ram.[30]

The Thebans, and those who by the Theban example will not touch sheep, give the following reason for their ordinance: they say that Heracles [Herodotus' name for the god Shu, a footnote tells us] wanted very much to see Zeus and that Zeus did not want to be seen by him, but that finally, when Heracles prayed, Zeus contrived to show himself displaying the head and wearing the fleece of a ram which he had flayed and beheaded. It is from this that the Egyptian images of Zeus have a ram's head; and in this, the Egyptians are imitated by the Ammonians, who are colonists from Egypt and Ethiopia and speak a language compounded of the tongues of both countries. It was from this, I think, that the Ammonians got their name, too; for the Egyptians call Zeus “Amon”. The Thebans, then, consider rams sacred for this reason, and do not sacrifice them.

On the other hand, in Lower Egypt, at the town of Mendes, it was goats that were not sacrificed.

All that have a temple of Zeus of Thebes or are of the Theban district sacrifice goats, but will not touch sheep. For no gods are worshiped by all Egyptians in common except Isis and Osiris, who they say is Dionysus; these are worshiped by all alike. Those who have a temple of Mendes or are of the Mendesian district sacrifice sheep, but will not touch goats.

In the "Bembine Tablet", that a goat is being sacrificed doubly confirms that these are priests of Amon.

It is possible that by the 17th century there were also images of a different god, clearly a creator-god, although probably they would not have known it was different from that of the Bembine Tablet. At Dendera, an easily accessed temple on the Nile, the god Khnum is shown at a potter's wheel making a human child.

But the 17th century would not have known about Khnum in this context. Instead, from another Greek text, they would have identified it as another god, Thoth. In the excerpts from otherwise lost ancient Hermetica contained in a work by the ancient anthologizer Strobaeus (a work known by the late Renaissance), there is one, Excerpt 23 in Scott's translation, in which Hermes himself gets the job of forming the human body. Originally, the dialogue relates, the God of all gave the souls the job of forming bodies for themselves out of a mixture of water and earth, in which he had breathed in a certain life-giving spirit. Instead, they created all the various animals and set themselves up as creator-gods. The "god of all" wanted to punish the souls for their audacity, by imprisoning them in matter. He gave the job of fashioning the material organism to Hermes:[31]

"And I," said Hermes, "sought to find out what material I was to use, and I called upon the Sole Ruler, and he commanded the souls to hand over the residue of the mixture. But when I received it, I found that it was quite dried up. I therefore used much water for mixing with it; and when I had thereby renewed the liquid consistency of the stuff, I fashioned bodies out of it. And the work of my hands was fair to view, and I was glad when I looked on it. And I called on the Sole Ruler to inspect it, and he saw it, and was glad; and he gave the order that the souls should be embodied."

The result of course was much wailing and weeping on the part of the souls thus imprisoned, but they could do nothing. From this perspective, Khnum drops out in favor of Hermes/Thoth as the potter god. It is also an example of how the Magician as Hermes combines the elements, or at least two of them.

Other ancient Egyptian images of Khnum's headpiece showed, besides the horizontal horns, a circle between two other horn, at right above (I have not been able to determine where it is from). Probably it was painted red, just as the bowl in the center of the Magician's hat was painted red in the Tarot of Marseille and even in the earliest version by Bembo, done around the same time and in the same place as antiquarian merchant Cyriaco d'Ancona, who had done five volumes of sketches of monuments in Greece and Egypt, settled before his death.[32] The parallels are at least striking. And the god Thoth was to receive a striking association with the tarot in late 18th century Paris.

3. 1780s Paris: De Gébelin, de Mellet, and Etteilla

In 1781 the French-Swiss antiquarian Court de Gébelin, in the eighth volume of

a series named Le Monde Primitif (The Primitive World), advanced his

theory that the tarot was of Egyptian origin. About the Magician, he points out

that the term in French, Bateleur, derives from baston, meaning

"stick", which of course is the attribute of stage magicians. Gébelin also called him "the player with

cups", presumably meaning the game in which one tries to guess which cup

the little ball or shell will end up in. In either case, he was an illusionist.

If the tarot is about life, then the Magician deals with the illusions of life.

Gébelin wrote:[33]

At the head of all the trumps, it indicates that all of life is only a dream that vanishes away: that it is like a perpetual game of chance or the shock of a thousand circumstances which are never dependent on us, and which inevitably exerts a great influence on every general administration.

"Between the Fool and the Magician, man is not

well," Gébelin concludes. This is much like the Anonymous of c. 1565

Italy.

In the same volume of Le Monde Primitif, Gébelin inserted another essay

on the tarot, this one by his friend the Comte de Mellet, for whom the tarot

was the “Book of Thoth,” the Egyptian god of magic, medicine, and wisdom whom

the Greeks and Romans identified with their Hermes and Mercury.[34]

It is then a small step to imagine the Magician of the tarot as such a figure,

if not Thoth himself then a follower in his teachings.

De Mellet also outlined a system of divination using the tarot, the first such

system in print. It is not, the first system known, as the rudiments of

another, associating each card with a specific idea, has also been found in

manuscript form buried in a Bologna library, dating to 1750; in addition, there

is a record of a woman being subject to legal action for tarot-reading in

Marseille of 1759,[35]

and divination by the tarot is mentioned in 1770 Paris at the end of a book on

fortune-telling with ordinary cards;[36]

its author was a print seller named Alliette, writing under the pen-name

"Etteilla." As with the system in Bologna, each card was associated

with a particular idea designated by a word or phrase. In 1783 the same author

published, after some problems with the censor, a list of such words and phrases

for all 78 cards. In 1789 he printed his own unique divinatory tarot deck, with

upright and reversed keywords printed on each card. It is still in print, with

a few modifications. His system remains one layer of modern cartomancy.[37]

Etteilla wrote that he learned tarot divination from an old man named Alexis,

the grandson of a better known one, also named Alexis but called “Piémontois”

(30).[38]

There was in fact an “Alessio Piemontese,” at least someone using that

pseudonym, a 16th-century Italian humanist who published a book of

“empiric” medical recipes, soon translated into French and other languages. He,

or someone claiming to him, said that in Naples he and others had collected and

tested whatever they could find of folk remedies; those that passed were

included in the book, which was translated into many languages; the French

version is even online, with his nom de plume in French.[39]

Etteilla’s “Alexis” offered a different kind of medicine, “médecine de

l’esprit”—medicine of the spirit or mind, whose justification, when all was

said and done, was still that it worked. The mountebank of old is slowly

becoming the Jungian card-reader of today, hopefully in touch with the

archetypal wisdom inside all of us that the cards may help unlock.

Debout, ce no. 15 présage une maladie pour laquelle on dépensera de grosses

sommes sans réaltat. Un charlatan viendra enfin, qui, avec une potion légère,

vous rendra la santé pour longtemps.

(Upright, number 15 presages an illness for which one will spend large

amounts of money without result. Finally a charlatan will come who, with a

light potion, will give you health for a long time.)

For some, it seems, the medical establishment did not have a

good reputation.

Etteilla was the first to explicitly associate astrological signs with tarot

cards: he associated his cards nos. 1-12 with the zodiac and the number cards

of the suit of Coins, cards nos.68 -77 with the planets and a few other

symbols. The appropriate zodiacal symbol was put on each card next to the upper

left corner of the picture; in Coins, it was put inside the circles

representing coins or below them. As number 15, the Magician card got no

such association and no astrological symbol, as can be seen above.[42]

Thus far, the Magician is a mixed bag. Of ill repute and a purveyor of

worthless medicines in some Renaissance writings, the historical imagery also

suggests a conveyor of wisdom and a healer in the medical sense

4. The card in modern occultism

Eliphas Lévi

In fortune-telling, Etteilla's cards eclipsed the more traditional "Tarot

of Marseille" referred to by de Gébelin and de Mellet, until Eliphas Lévi,

the founder of modern occultism, included a section on the tarot in his Doctrine

and Ritual of High Magic. His account presents the cards in the traditional

French order, with much the same subjects as Gébelin, albeit with variations in

detail to suit Lévi's own purposes. For this card, still of a

"Bateleur", he says, in part I of the work: [43]

A la première page du livre d'Hermès; l'adepte est représenté couvert d'un

vaste chapeau qui, en se rabattant, peut lui cacher toute la tète. Il tient une

main élevée vers le ciel, auquel il semble commander avec sa baguette, et

l'autre main sur sa poitrine; il a devant lui les principaux symboles ou instruments

de la science, et il en cache d'autres dans une gibecière d'escamoteur. Son

corps et ses bras forment la lettre Aleph, la première de l'alphabet, que les

Hébreux ont empruntée aux Egyptiens; mais nous aurons lieu plus tard de revenir

sur ce symbole.

(On the first page of the Book of Hermes the adept is depicted with a

large hat, which, if turned down, would conceal his entire head. One hand is

raised towards heaven, which he seems to command with his wand, while the other

is placed upon his breast; before him are the chief symbols or instruments of

his science, and he has other hidden in a juggler's wallet. His body and arms

form the letter ALEPH, the first of that alphabet which the Jews borrowed from

the Egyptians: to this symbol we shall have occasion to recur later on.)

Il n'y a qu'un dogme en magie, et le voici le visible est la manifestation

de l'invisible, ou, en d'autres termes, le verbe parfait est. dans les choses

appréciables et visibles. en proportion exacte avec les choses inappréciables a

nos sens et invisibles à nos yeux. Le mage, une main vers le ciel et abaisse

l'autre vers la terre, et il dit: "Là haut l'immensité la-bas est

l'immensité encore; l'immensité est l'immensité." Ceci est vrai dans les

choses visibles, comme dans les choses invisibles.

(There is only one dogma in Magic, and it is this: The visible is the

manifestation of the invisible, or, in other terms, the perfect word, in things

appreciable and visible, bears an exact proportion to the things which are

inappreciable by our senses and unseen by our eyes. The Magus raises one hand

towards heaven and points down with the other to earth, saying: "Above,

immensity: Below immensity still! Immensity equals immensity." This is

true in things seen, as in things unseen.)

About the Aleph, the body with raised and lowered arms, he adds (p. 120, p. 36 of translation):

C'est l'expression du principe actif de toute chose, c'est la création dans

le ciel, correspondant à la toute-puissance du verbe ici-bas Cette lettre à

elle seule est un pantacle, c'est-à-dire un caractère exprimant la science

universelle

(It is the expression of the active principle of everything; it is the creation

in heaven, corresponding to the omnipotence of the word here-below. This

letter in itself is a pantacle, that is to say a character expressing universal

science.)

The word "pantacle" is Lévi's invention, which he

has defined for us as a kind of talisman.

Then in Part 2 (p. 345 of original, in Google Books, p. 363 of translation) he

says:

L'être, l'esprit, l'homme ou Dieu; l'objet compréhensible; l'unité mère des nombres, la substance. Toutes ces idées sont exprimées hiéroglyphiquement par la figure du BATELEUR. Son corps et ses bras forment la lettre Aleph; il porte autour de la tête un nimbe en forme de ∞, symbole de la vie et de l'esprit universel devant lui sont des épées, des coupes et des pantacles, et il élève vers le ciel la baguette miraculeuse. ïl a une figure juvénile et des cheveux bouclés, comme Apollon ou Mercure il a le sourire de l'assurance sur les lèvres et le regard de l'intelligence dans les yeux..He is not only the Magus, but the Judeo-Christian God, the metaphysical categories of "being" and "mind." With him, too, we get the first explicit mention of the sideways 8, or infinity sign, "symbol of life and the universal mind [or spirit]," in place of the wide-brimmed hat. In French the word esprit means both "spirit" and "mind." The word "Juggler" in Waite's translation does not have the modern sense of a person skilled in keeping a large number of objects in motion, but the archaic sense of a street performer. The term bateleur in French goes back to the Middle Ages, where it was "basteleur"; "baastel" meant "puppet" according to Merriam-Webster online, but the term applied to any performer. On the card, of course, he uses small objects.

(Being, mind [or spirit - MH], man or God: the comprehensible object; the mother unity of numbers, the first substance. All these ideas are expressed hieroglyphically by the figure of the JUGGLER [BATELEUR]. His body and arms form the letter ALEPH; around his head he bears a nimbus in the form of the symbol of life and the universal spirit; in front of him are swords, cups and pentacles; he uplifts the miraculous rod towards heaven. He has a youthful figure and curly hair, like Apollo or Mercury; the smile of confidence is on his lips and the look of intelligence in his eyes.)

In calling him "the comprehensible object," Lévi is defining him not as the God of the abyss, the incomprehensible No-thing about which nothing could be said, but rather the creator-god, first cause of the creation. If the Fool is defined by absence, the zero, the Magician is defined by presence, but also a presence that points to absence, the unseen creator, just as the Bateleur's illusions point to, without betraying, something unseen that causes the illusion.

The Bateleur is also Unity and, more specifically, the "unity of numbers." This is a Pythagorean-Platonic way of thinking. On the one hand, the four types of objects on his table are the four elements, which Plato's Demiurge[44] mixed to form the universe. They are also the combination of talents and circumstances that form the birth conditions of every human. To a Pythagorean this situation is analogous to the role of 1 with the numbers. By successive addition it is the creator of every other number. It also is every other number, inasmuch as every number is an addition of ones. From this point of view it is obvious that the Magician has to be card one. In fact, we might wonder if the image of a magician was put in the sequence precisely for this purpose, to start things off. Pythagorean thinking was hardly foreign to 15th-century Italy.

Kabbalistic associations are integral to Lévi's interpretation of the tarot. In both Greek and Hebrew the letters are also used as numbers, in order up to ten, with number eleven as "ten and one", and a new letter for twenty, etc.Besides identifying him with Aleph, he also makes the first explicit association between the card and a metal or planet that I have found. In the quotation below, he identifies the Bateleur with alchemical Mercury, as part of a broader thesis that the tarot simply repeats some of the concepts of alchemy. He writes (Part 1, pp. 170-171, trans. p. 267-268):

Les figures cabalistiques du juif Abraham, qui donnèrent à Flamel l'initiative de la science, ne sont autres que les vingt-deux clefs du Tarot, imitées et résumées d'ailleurs dans les douze clefs de Basile Valentin. Le soleil et la lune y reparaissent sous les figures de l'empereur et de l'impératrice; Mercure est le bateleur; le grand Hiérophante, c'est l'adepte ou l'abstracteur de quintessence.

(The cabalistic figures of Abraham the Jew, who gave Flamel the initiative of science, are none other than the twenty-two keys of the Tarot, imitated and summarized elsewhere in the twelve keys of Basil Valentine. The sun and the moon reappear under the figures of the emperor and the empress; Mercury is the bateleur; the great Hierophant is the adept or the abstractor of quintessence.)

By "Abraham the Jew" Levi is referring to a mysterious 14th century Jew who according to 16th and 17th century sources gave Nicholas Flamel an equally mysterious book, by means of which he was able to amass a large fortune, most of which he devoted to the alleviation of the poor. Also, since his tomb was found empty, it was imagined that he had achieved the secret of bodily immortality. Mercury is mentioned in a French text of 1612 century, published in his name, Exposition of the Hieroglyphicall Figures (in archive.org). One image there describes Mercury (page 12 of English ed. of 1624, in archive.org). The image below is from a c. 1700 copy in French, wdownloaded from the website of the Science Museum, from their ms. 383, there called "Trésor des Trésors." The text identifies the figure on the cloud as Death.

We might wonder whether the association of the Bateleur to Mercury was Lévi's invention or if

he was simply repeating common knowledge. In the 15th century, the image of a sleight-of-hand

artist, in a series of prints or manuscript illuminations known as the

"Children of the Planets," was often associated with the Moon, as in

the example at right.[45]

The Moon was identified with the Virgin Mary, taking the place of the Roman

Diana. Diana and her nymphs were famous for their virginity; moreover, Diana's

cult center was Ephesus, the same place that was associated with the Virgin in

her later years. The Virgin was identified in art with the Moon, in that she

was represented sitting or standing on the horns of the crescent moon, as in the famous

image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

We might wonder whether the association of the Bateleur to Mercury was Lévi's invention or if

he was simply repeating common knowledge. In the 15th century, the image of a sleight-of-hand

artist, in a series of prints or manuscript illuminations known as the

"Children of the Planets," was often associated with the Moon, as in

the example at right.[45]

The Moon was identified with the Virgin Mary, taking the place of the Roman

Diana. Diana and her nymphs were famous for their virginity; moreover, Diana's

cult center was Ephesus, the same place that was associated with the Virgin in

her later years. The Virgin was identified in art with the Moon, in that she

was represented sitting or standing on the horns of the crescent moon, as in the famous

image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

However, the association does not actually

identify the Bagattella with the moon: he is her "child." Mercury is

not the child of the moon-goddess in Greco-Roman mythology; yet in the

so-called "emerald tablet" of medieval alchemy, the child of the sun

and the moon, although not named, was probably understood as alchemical Mercury.[46]

A relationship to the god Mercury is also fitting for another reason. Before he

was two days old, Hermes (the Greek original of the Roman Mercury) defined

himself as a trickster, against his brother Apollo.[47]

Also, in Renaissance astrology the god governed, among others, people “given to

Divination and the more secret knowledge,” albeit sometimes maliciously.[48]

Since Mercury was associated with eloquence—like that of the mountebank before

the crowd--he was also said to govern afflictions of the mouth, throat, and

brain, and the herbs to cure these afflictions, as well as herbs that promote

divination or have other associations to his myth.[49]

One example: Lilly says that herbs growing on sandy ground are sacred to

Mercury. It was in such ground that the god made Apollo’s cows’ hooves point in

the opposite direction to where they were going.

A further association to Mercury is in the Greek's identification of the

Egyptian god Thoth with their Hermes. In this context there is also, of course,

the legendary Hermes Trismegistus, Thrice-Great, who was imagined either as a

descendant of Thoth or somehow the embodiment of the god himself.

Paul Christian, Falconnier and Wegener, A. E. Waite

Lévi's follower Paul Christian, in 1863 and 1870, continued most of Lévi's

characterizations, but reconciled apparent contradictions by saying that the

card has meaning on three levels: divine, intellectual, and human: [50]

A = 1 exprime dans le Monde divin l'Être absolu, qui contient et

d'ou émane l'infini des possibles. Dans le Monde intellectuel, l'Unité,

principe et synthèse des nombres; la Volunté, principe des actes. Dans le Monde

Physique, l'Homme, le plus haut placé des êtres relatifs, appelé à s'élever,

par une perpétuelle expansion de ses facultés, dans les sphères concentriques

de l'Absolu.

L'arcane 1 est figuré par le Mage, type de l'homme parfait, c'est-à-dire en

pleine possession de ses facultés physiques et morales.

(A-1 expresses in the divine world the absolute Being who

contains and from whom flows the infinity of all possible things; in the intellectual

world, Unity, the principle and synthesis of numbers; the Will, principle

of action; in the physical world Man, the highest of all living

creatures, called upon to raise himself, by a perpetual use of his faculties,

into the concentric spheres of the Absolute.

Arcanum 1 is represented by the Magus, the type of the perfect man, in full

possession of his physical and moral faculties.)

Lévi had emphasized what he considered the Jewish aspects

of the tarot. How a woodcut card representing God was permitted by the first

commandment, "Thou shalt not make graven images" he did not say,

Christian claims to find the Egyptian basis, including a 22-letter alphabet

that like the Hebrew letters did double duty as numbers. Not surprisingly, they

are rather similar to their Hebrew counterparts; after all, the Jews spent

many years in Egypt.

Christian takes over Lévi’s imagining of the card but with some differences, in particular, he relates it to power (Ibid):

La main droite du Mage tient un sceptre d'or, figure du commandement, et

s'élève vers le ciel, en signe d'aspiration à la science, à la sagesse, a la

force. La main gauche étend l'index vers la terre, pour signifier que la

mission de l'homme parfait est de régner sur le monde matériel. Ce double geste

exprime encore que la volonté humaine doit refléter ici-bas la volonté divine,

pour produire le bien et empêcher le mal.

(The Magus holds in one hand a golden scepter, image of a commend,

raised toward the heavens in a gesture of aspiration towards knowledge,

wisdom and power. The index finger of the left hand points at the ground,

signifying that the mission of the perfect man is to reign over the material

world. This double gesture means that human will ought to be the embodiment of

divine will, promoting good and preventing evil.)

"Will" is in fact the one word that Christian uses

to sum up the meaning of the card. Other details are his belt of a serpent

biting its tail, to represent eternity, a cubic stone instead of a table, and a

cross engraved on the coin. He does not tell us what the stone represents until

discussing Arcanum IV, the Emperor, where, as "the perfect solid”, it

"signifies the accomplishment of human labors". The cross

"annonce la future ascension de cette puissance dans les sphères de

l'avenir" ("announces the future ascension of this power [the power

of the will, which the coin signifies] into the spheres of the future").

Unlike Gébelin, who presented the traditional Platonic/Stoic scorn of the

physical world, "in which nothing depends on us,"[51]for Christian the material world was the sphere of action, of which the

Magician is the rightful master who imposes his will upon it.

This rather romantic view of the

Magician defines him as Magus rather than performer of tricks, hero rather than

trickster. Substituting a raised staff for Lévi's raised arm, it was

Christian's image rather than Lévi's captured in the 1896

"Egyptian" version by Maurice Wegener for Robert Falconnier, adding a

comet to indicate the descent from above (near right).[52]. The Ibis on the stone is a nice touch: it is the bird sacred to Thoth. And while Levi had assumed that the Magician's hand holding the scepter was "uplifted" as well as the wand itself, as in the Tarot of Marseille, Christian only mentioned the scepter. Falconnier and Wegener, following Christian to the letter, show only the scepter "raised toward the heavens," and not the hand.

This rather romantic view of the

Magician defines him as Magus rather than performer of tricks, hero rather than

trickster. Substituting a raised staff for Lévi's raised arm, it was

Christian's image rather than Lévi's captured in the 1896

"Egyptian" version by Maurice Wegener for Robert Falconnier, adding a

comet to indicate the descent from above (near right).[52]. The Ibis on the stone is a nice touch: it is the bird sacred to Thoth. And while Levi had assumed that the Magician's hand holding the scepter was "uplifted" as well as the wand itself, as in the Tarot of Marseille, Christian only mentioned the scepter. Falconnier and Wegener, following Christian to the letter, show only the scepter "raised toward the heavens," and not the hand.

Papus

Papus, following Christian in 1889, returned to Lévi's orientation toward the

Hebrew letters, as opposed to Christian's Egyptian letters. His only concession

to Egypt is in seeing the myth of Osiris, Isis, and Horus in the cards, in which

card one is Osiris. For him Christian's three levels (divine, intellectual,

physical) then become God (Osiris), Man (Adam), and the Universe (the Natura

Naturans, "nature naturing", a term borrowed from Spinoza,

meaning the universe as a self-forming and evolving creation).[53]

Besides continuing Lévi's associations to the Hebrew letters, giving Aleph to the Magician, he also assigned

the Magician to the sephira Kether, Hebrew for "Crown" and the

highest sphere on the Kabbalists' Tree of Life (Lévi himself, in Dogme

et Rituel, part 2, p. had associated Kether with the World card). In either

case Kether is the source of initiative in all the areas expressed by the rest

of the Tree.[54]

He also made the four objects prefigurations of what for him is the basic

pattern of the tarot, which is to go from active (Osiris, the wand, and the

Magus) to passive (Isis, the cup, and the Popess), followed by their

equilibrium (Horus, the sword and the bird on the Empress's shield)

and transformation (the coin and the new Osiris, the Emperor).[55]

Oswald Wirth

Wirth, who drew the new designs featured in Papus's 1889 book, in his own book of 1927 builds on Lévi

and Papus, retaining much of the traditional TdM design but incorporating some of Levi's innovations. Like Lévi, he sees the posture as conveying the shape of

Aleph.

The hat, as in Lévi's drawing, resembles the infinity sign and is not

replaced

by it. As in the Tarot of Marseille, the wand focuses on the coin, as does the figure's right hand.

Wirth expresses the three levels of meaning somewhat differently from Papus and Christian. On the divine level it is indeed God, but it is God "seen as the great suggestive power of all that is accomplished in the Cosmos."[56] So it is an immanent rather than transcendent God, and Papus's two levels, divine and physical, become one. The level of Man still exists, but as "the seat of individual initiative, the center of perception, of conscience, and of will power" (Ibid.). The French word "conscience" means both "conscience" and "consciousness"; so it is not clear which is meant, or perhaps both. In any case, "He is the ego called to make our personality, for the individual has the mission to create himself" (Ibid.).

Levi had said that the Magician was "active"; but did that mean physically as well as mentally? Wirth says (Ibid.):

One feels that the Magician cannot stay in repose. He plays with his wand, he monopolizes the attention of the spectators and dazzles them with his continuous juggling and his contortions, as much as by the mobility of his facial expressions.

This is the development of the ego as an object for

others,

what Jung would call a persona, the face we present to others: he is "a

character full of shrewdness, hardly inclined to to betray the depths of

his thoughts" (Ibid., p. 64).

Wirth identifies the

figure 8 lying on its side with the ecliptic, representing our "mental

sky" (Ibid.) That only three legs of the table are visible suggests Sulphur,

Salt, and Mercury, the "three pillars of the objective world, supports

to the substance perceive by our prime senses" (Ibid.) There are

likewise three objects on the table, the fourth being the wand in his

hand, which points to the gold shekel, or pentacle. The wand is thus "as

if to concentrate his personal active emanation of life onto it." The

coin is thus an "accumulator" for the "charges taken from is

surroundings." It is also the "fire from heaven" now in the "occultly

magnetized" object. Appropriately, Wirth colors the top knob of the wand red; the other end is blue, for the "magnetism" in the air.

Like the other theorists, Wirth identifies the four objects (the three on the table plus the wand in his hand) with the four

suit-signs and the four elements. But he also identifies them with a

magical formula: To Know (cup), To Dare (sword), To Desire (wand), To be Silent

(pentacle). Then the initiated Magician has accomplished four victories (Ibid.):

The victory won over Earth awards

us the pentacle, that is to say, the vital point of support for all action

needed.

By confronting Air with audacity the knight of Truth wins himself the Sword,

symbol of the Word which puts to flight the phantoms of Error.

To triumph over Water is to conquer the Holy Grail, the Cup out of which Wisdom

drinks.

Tested by Fire, the Initiated obtains at last the emblem of supreme command,

the Wand, the king's scepter, for he reigns through his own will merged with the

sovereign will.

There thus seems to be a beginning-Magician, creating his ego/persona, and an end-Magician, which merges with the divine.

A. E. Waite and Paul Foster Case

For the Golden Dawn, based in England, in contrast to the French occultists' Aleph and Kether, the Magician was associated with Beth and the path between Kether and Binah. The online Lleweleyn Encyclopedia says:[57]

The Path of the Magician connects Kether to Binah and is the beginning of material production. The letter Beth means house, and the Magician himself is the house in which the Divine Spirit dwells. He is the director of channeled energy. . . . The paths of Beth and Mercury link Kether, the Crown, with Binah. The Magician, therefore, is reflected in the Intellect which stores and gathers up knowledge and pours it into the House of Life, Binah. . . . It can help you to develop your ability to express yourself in public, as well as the ability to think clearly. It helps you to develop your intellectual mind, your creativity, your writing ability, your love of science and books, and your effective use of memory.

Binah means "understanding" or "intelligence"; hence the emphasis on "knowledge," and a characterization of the card in terms of clarity of thought. This emphasis is not shared by Lévi, Christian, and Papus, who do not use "paths" on the Tree of Life and seem to see the card primarily as creativity, initiative, and willpower, including the use of intellect, perhaps in certain tools on his table (the sword of intellect or the cup of knowledge), among other things.

The Golden Dawn also identified the card with the planet Mercury, thereby accruing to it all the associations of the god as well. Waite, in his account of the card in Pictorial Key to the Tarot, 1911 (online in sacred-texts.com), mentions only Apollo: "A youthful figure in the robe of a magician, having the countenance of divine Apollo, with smile of confidence and shining eye."[58]

In his depiction of the Magician, Waite follows Levi's account of the "uplifted" hand, with the raised wand a virtual extension of the hand, even more uplifted than in the Tarot of Marseille. Waite says of it:

This dual sign is known in very high grades of the Instituted Mysteries; it shows the descent of grace, virtue, and light, drawn from things above and derived to things below. The suggestion throughout is therefore the possession and communication of the Powers and Gifts of the Spirit.

Like Lévi, he is not so effusive about mastering the material world as Christian. So it remains unclear what makes him a Magician. An innovation is the serpent biting its tail around his waist: "This is familiar to most as a conventional symbol of eternity, but here it indicates more especially the eternity of attainment in the spirit."

And on the siginificance of the sideways 8 (Ibid.).

The mystic number is termed Jerusalem above, the Land flowing with Milk and Honey, the Holy Spirit and the Land of the Lord. According to Martinism, 8 is the number of Christ.

Waite does not mention the Golden Dawn's identification of the card with Beth. However, that identification is seen explicitly in the card of Paul Foster Case, which otherwise is similar to Waite's. He writes: [59]

the earliest form of the letter

Beth was a picture of an arrow-head, The sharpness of an arrow-head suggests

acuteness and power to penetrate. Thus Beth is a symbol of the mental qualities

of nice perception, keen and penetrating insight, and accurate estimation of

values.

The fundamental mood represented by this form of the letter, connected as it is

with hunting and warfare, is alert intentness. Right use of the mental powers

pictured by the Magician calls for alert, watchful attention to the

succession of events constituting waking experience. . . .

An arrow-head has no energy of its own. The force whereby it cleaves the mark

is a derived force. The arrow is merely the means whereby power is transmitted.

An arrow-head is an instrument which transforms propulsion into penetration. It

specializes bow-force into arrow-force.

There is also the meaning of Beth as "house": [60]

The letter-name means ”house,” which is a definite location used as an abode. In the sense used here, it refers to whatever form may be termed a dwelling-place for Spirit, and the form particularly referred to in this lesson is human personality, for Personality is a center through which the Spirit or real Self of man expresses itself. Do not be abstract about this. Think of your personality as a center of expression for your own inner Self. Try to realise that this is what Jesus meant when he said, "The Father who dwelleth in me. He doeth the works.”

With this, his interpretation of the card is rather clear (Ibid., p. 1). It is the same "will" as for the French occultists:

Geometrically the number 1 is a point, particularly, the CENTRAL POINT. In the Pattern of the Trestleboard, the statement attributed to 1 is: "I am a center of expression for the Primal Will-to-good which eternally creates and sustains the universe.” The beginning of the creative process is the concentration of the Life-power at a center, and its expression through that center.

It is perhaps of interest that the "primal will" here is not a limitless set of possibilities, but limited to those that tend toward the good: it is a "will-to-good". How does that focus come about? It is precisely through the concentration of Life-power through careful attention to "the succession of events constituting our waking experience" (Ibid., p. 3):

The practice of concentration enables one to perceive the inner nature of the object of his attention. This leads to the discovery of natural principles. By applying these, one is able to change his conditions. Hence concentration helps us solve our problems.In the context of problem-solving (Ibid., p. 1):

Self-consciousness initiates the creative process by formulating premises or seed-ideas. Subconsciousness accepts these as suggestions, which it elaborates by the process of deduction, and carries out in modifications of mental and emotional attitudes, and in definite changes of bodily function and structure.He puts the point about "seed ideas" in another way in the next lecture, as the context for the creataive process:

By determining what you want to be and do, you have taken this first step. You have set a mark at which you aim the whole energy of your life.The Magician card pertains to the first part, the formulation of seed ideas for one's life. The Popess and the Empress have to do with the subconscious and actualizing these ideas in action. This is the process that Papus called Active/Passive/Equilibrium, between Magician/Popess/Empress. But for Case it is somewhat different (Ibid., p. 4):

One important point to observe is that the Magician himself is not active. He stands perfectly still. He is a channel for a power which comes from above his level, and after passing through him, that power sets up a reaction at a level lower than his.

It is the movement from Spirit, symbolized by the upside down 8 as infinity sign (lesson 6, p. 5), to Matter, with the Magician in between. However, the active Spirit seems to be the Fool, leaving the Magician as an especially attentive observer of his or her inner experience. Put in another way (lesson 6, p. 3):

the act of establishing contact

with super-consciousness is the highest and most potent use of self-conscious

awareness.

First we observe what goes on. Then we use inductive reasoning, reasoning from

Observed effects to inferred principles, to reveal that lies hidden behind the

veil of appearances. This leads to the discovery that the succession of events of which our

personal experience is a part is under the direction of a supervising Intelligence,

higher than the objective mind of man.

This sounds somewhat like a description of the scientist, discovering the underlying principles of the universe through generalizations from particular observations; but unlike many scientists, Case thinks that observation will show direction of events by a "supervising intelligence." In addition, there is the wand, which symbolizes a power beyond that of the usual scientist. The wand symbolizes libido, which can be experienced sexually but in the Magician's hands is transmuted into mental forms (lesson 6, p. 4):61

THE PRACTICE 0F MENTAL CREATION AND CONSTRUCTIVE THINKING AUTOMATICALLY TRANSMUTES THE DRIVE OP THE LIBIDO FROM PHYSICAL FORMS OF EXPRESSION TO MENTAL FORMS WHICH RELIEVE BOTH PHYSICAL AND PSYCHICAL FISSURES, SUCH AS ACCUMULATE WHEN THIS ENERGY IS NOT UTILIZED.

The wand is thus naturally associated with the element of fire. He continues (lesson 6, p. 7):

The cup, made of silver, metal of the Moon, is a symbol of memory and IMAGINATION, and of the element of water. The sword, of steel, is related to Mars; and stands also for ACTION, and for the element of air. The coin or pentacle is related to Saturn; and it also represents FORM, and the element of earth.

These four tools also represent the power of the Word, in

particular that of JHVH, one letter for each tool. All of them combined are needed to enable the energy focused by self-consciousness to have its effect on subconsciousness, which seems to be more than just the subconscious personality of the magician, but includes his body and other energy-patterns we call material.

Finally, one result of concentrated attention is the realization of our

essential connection to others (Ibid., p. 10).

In partly developed persons the objective mind creates the illusion that the SELF is peculiar to a particular personality— that the personal "self” is a unique identity, separate from all others. Concentration and meditation lead to freedom from this illusion, by enabling us to see that it is an illusion. When you come to this recognition, you will no longer think and act as if you were a separate being. Then you will know that your personality is an instrument through which the One Force typified by the Fool finds expression.

5. The Jungian turn

Jung, as a scientist of the unconscious, locates the magician as a figure in the collective unconscious. It permeates fairy tales in every culture and occasionally also the dreams and fantasies of people today. In literature - pre-eminently, Goethe's Faust - and now, with the advent of computer-generated special effects, movies by the dozen - the magician also plays a powerful role. Jung has written so much about the magician that it is difficult to summarize his views.

The magician first appears as the figure of Philemon in The Red Book, a character he first met in a dream, then painted (at right), then engaged with in "active imagination, in which he enters the world of the dream in his imagination. Philemon is a retired magician who lives with his wife Baucis in a "small house in the country fronted by a large bed of tulips." [61] In Jung's imagination, he had been given a black magic rod by his soul, but didn't know what to do with it, [62] so he journeyed to Philemon. He gets mostly riddles. It seems to be a reaction aginst those who claim, like Levi, that the magician is simply exercising his rational faculties in an area where not much is known about the mechanism. That is to say, it is not about control over phenomena, inner or outer, based on inductive observation of what follows what in experience. Philemon says, “Above all you must know that magic is the negative of what one can know.” [63] In what follows, Philemon functions in the role of another archetype, the Wise Old Man. Being old, he is not the same as the tarot figure; all that unites them is their experience with magic.The name Philemon is one already known to Jung. The couple

first appeared in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8:547-610) as an old couple who

took into their home and fed the disguised Jupiter and Mercury when no one else

would, including wine from a mixing bowl that refilled of its own accord. The

magic came from the gods, of course, but it was the old couple whose actions were

causing it to happen. That said something about the nature of magic, apparently, that it was a gift from the gods. Also, if one is a good person, then magic could be one's reward.

In Greco-Roman myth, however, the gods were capricious, and they not only allowed but perpetrated all kinds of mischief. Christianity changed all that. But there were still black magicians, who got their power from devils. If God is all-good and all-powerful, why does he produce, or even allow, beings whose nature it is to do evil? The Book of Job answered that it was to test his faithful, to see if they would maintain their faith in bad times as well as good. But is the horrible suffering of plagues and wars necessary for such a purpose? It would appear precisely that man is to use his reasoning ability to overcome such evils, as opposed to superstitions like a belief in magic.

Jung has another idea, namely. that the problem is that of splitting good from evil in the first place, which he attributes to Christianity, as a moral reaction to their unity. However, if the two are brought together, then “we lose direction.”[64] Jung remembers that his Philemon has a serpent companion (at his left in the painting above):[65]

Your wisdom is the wisdom of serpents, cold, with a grain of poison, yet healing in small doses. Your magic paralyzes and therefore makes strong people, who tear themselves away from themselves. But do they love you, are they thankful, lover of your own soul? Or do they curse you for your magical serpent poison? They keep their distance, shaking their heads and whispering together.

Magic is disdained because it "has a grain of poison" that "paralyzes" people. So Philemon keeps his distance, too, unless he is called upon by someone, or unless he needs them:[66]

I praise, oh Philamon, your lack of acting like a savior: you are no shepherd who runs after stray sheep, since you believe in the dignity of man, who is not necessarily a sheep. But if he happens to be a sheep, you would leave him the rights and dignity of sheep, since why should sheep be made into men?

I get the geeling that Jung is not only praising Philemon, but also warning himself, in his clinical practice, to be careful about trumpeting his views about.

In Psychological Types, written only four years or so after his meeting Philemon, Jung articulates his fascination with the Magician as a figure in the collective unconscious:[67]

The Promethean defiance of the accepted gods is personified in the figure of the medieval magician. The magician has preserved in himself a trace of primordial paganism; he possesses a nature that is still unaltered by the Christian splitting [i.e., between Christ and the Devil], which means he has access to the unconscious, which is still pagan, where the opposites still lie side by side in their original naïve state, beyond all sinfulness, but if assimilated into conscious life, produce evil and good with the same daemonic force (“Part of that power which would / Ever work evil yet engenders good”). Therefore he is a destroyer as well as savior. The figure is therefore pre-eminently suited to become the symbol-carrier for an attempt at unification.

In later work Jung and his colleagues illustrate this conception in terms of the magicians of fairy tales and dreams. They imprison princesses in magic castles and put spirits in bottles. Their transformative powers change people to animals and back again, and can even raise from the dead. They also change ordinary materials into gold; in this way the alchemist is a magician, too, and Jung will soon be declare that the alchemist is better than the fairy tale at describing his power, even if still in projected form.

The Magician is also an unconscious figure responsible for a type of ego-inflation. Jung describes magician-possession as a typical stage in the individuation process of men. First is the discovery and management of the anima, a powerful unconscious female-imagined dominant with much "mana," that is, power to attract and dominate one. Recognizing its influence is to depotentiate it. But then:[68]

who is it that has integrated the

anima? Obviously the conscious ego, and therefore the ego has taken over the

mana. Thus the ego becomes a mana-personality. But the mana-personality is a

dominant of the collective unconscious, the well-known archetype of the mighty

man in the form of hero, chief, magician, medicine-man, saint, the ruler of men

and spirits, the friend of God. . . .

This masculine collective figure who now rises out of the dark background and takes possession of the conscious personality entails a psychic danger of a subtle nature, for by inflating the conscious mind it can destroy everything that was gained by coming to terms with the anima. . . .

Here is cause for serious misunderstanding, for without a doubt it is a question of inflation. The ego has appropriated something that does not belong to it. . . .

Thus he becomes a superman, superior to all powers, a demigod at the very least. "I and the Father are one"; this mighty avowal in all its awful ambiguity is born of just such a psychological moment.

He now can see into the secret workings of the psyche and so help others to heal. But others of his acquaintance are not impressed:[69]

But why does not this importance, the mana, work upon others? That would surely be an essential criterion! It does not work because one has not in fact become important, but has merely become adulterated with an archetype, another unconscious figure.

The Magician is for this person a trickster, for whom one who has experienced some benefit from Jungian analysis is fair game. What is necessary is to bring the new figure to consciousness, too, and thereby depotentiate it, resulting in an equilibrium between conscious and unconscious. That is where the “mana” goes:[70]

In this situation, then, the mana must rest with something that is both conscious and unconscious, or else neither. This something is the desired "middle point" of the personality, that indescribable something between the opposites, the reconciliation of the opposites . . .

This is the beginning of the transformation or rebirth. Magic occurs when consciousness and unconsciousness are in dialog.

Since Jung is describing the dream of a man, we might wonder if the same dream could have been had by a woman. I can see no objection in principle. Fairy tales and myths, Jung's other primary sources of archetypes, were for consumption of males and females equally. The Magician would be what Jung calls an "animus" figure for women. Post-Jungians such as James Hillman simply use "anima" for female figures and "animus" for male figures in the unconscious of either men or women.

Mercury, the astrological entity associated by some occultists with the card, makes his appearance in Jung’s writings by way of the alchemical Mercurius that Levi associated with it. As Sallie Nichols quotes Jung in her 1980 book Jung and Tarot, this Mercurius is both a "world-creating spirit" and the "transformative agent trapped in gross matter."[71] In an age when alchemy has been replaced with chemistry, he is the agent of change inside us transforming our own individual human nature. But the alchemists saw Mercurius also as a great poison and bringer of death: If it contains all opposites, that includes what Jung called the shadow, "qualities in ourselves which we prefer not to think of as belonging to us."[72]

Sallie Nichols says "All artists are magicians." [73] She compares Michelangelo with the alchemist. Just as the alchemist tried to free spirit from matter, so Michelangelo tries to bring out what is already there in the stone. His "captives" (example at left) show figures emerging from their stone fetters. Similarly, the writer's job is to liberate his or her ideas from their entanglement in excessive verbiage that obscures the essential meaning.

Freeing spirit from matter has as its psychological equivalent the freeing of libido, psychic energy, from the unconscious when it is trapped by depression or apathy. This is then the work of Mercurius, only not with materials in a laboratory but with oneself. The analyst is a kind of alchemist, helping a natural process.

But if the life force is Mercurius, we cannot assume that it is benign and always acts for the best. This figure from the collective unconscious acts in us without our awareness and can even masquerade as an angel. In "The Spirit Mercurius," Jung in 1942 characterized Mercurius as a storm god, the Wotan of the Germans, obviously referring to the spirit that had taken over Germany at that time. Reflecting on the fairy tale about a boy who finds a bottle containing the "spirit Mercurius," whom he lets go in exchange for certain magical powers, he observes nothing is said about what happens with the spirit: [74]

What happens when the pagan god Hermes-Mercurius-Wotan is let loose again? Being a god of magicians, a spiritus vegetativus, and a storm daemon, he will hardly have returned to captivity. . . . The bird of Hermes has escaped from the glass cage, and in consequence something has happened which the experienced alchemist wished at all costs to avoid. . . . They wanted to keep him in the bottle in order to transform him; for they believed, like Petosios, that lead (another arcane substance) was "so bedeviled and shameless that all who wish to investigate fall into madness thorough ignorance." The same was said of the elusive Mercurius, who evades every grasp - a real trickster who drove the alchemists to despair.

A magician, like a scientist, may like to think his magic is serving human needs. But one human "need" or "hope" may not jibe with another's, witness the justifications given by both sides in a war. Also, if we think of ourselves as great Magi, channels for something outside of ourselves to work miracles, we are probably being possessed by another archetypal image, that of the "mana personality," whom Jung calls "the magician" for short.

That, too, is part of the Mercurius archetype: he is indeed “a real trickster,” in the sense of an unconscious force that trick the ego just when the latter thinks it has mastered the unconscious. In the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, Hermes tricks Apollo: if Hermes is the trickster in that story, Apollo is ego-consciousness. Here there is an important difference between the Magician and the Devil. Nichols talks about the shadow in the tarot as "the Devil,"[75] but the Devil on that card is not in shadow: his horns are visible to all, as are the chains on the little devils below. He may correspond to a figure in our dreams, however, who symbolizes an unconscious energy-pattern that works against our conscious intent when we are awake.

In this regard she affirms the superiority of the Marseille card’s image over those of Waite and Case. Even if she is looking at a card that did not appear before around 1930 (not shown), it is not dissimilar to its historical antecedents (from left to right below: Noblet c. 1650; Chosson c. 1735; Waite 1909) [76]

As the white Yang “fish” of the Tai Chi symbol carries the dark eye of its counterpart, so embedded in the pure spirit of the Magician is a dark spot of feminine ambivalence.

The Marseille deck alone catches these subtle

nuances. In the Waite version, for example, only the positive yang aspects of

the Magician are shown. No motley Trickster at the crossroads, this magus

appears against a backdrop of pure, golden light among lilies and roses. . . .

The Marseille deck alone catches these subtle

nuances. In the Waite version, for example, only the positive yang aspects of

the Magician are shown. No motley Trickster at the crossroads, this magus

appears against a backdrop of pure, golden light among lilies and roses. . . .

The flamboyant hat . . . has disappeared entirely, leaving nothing but a small black leminiscate . . . offering little to nourish the imagination. The magician's snaky, gold-tipped curls have been replaced by the severe, no-nonsense coiffure of the priestly establishment. The table of the magician has also been tidied up; . . . we now find only the four objects representing the four suits, these all neately arranged and ready for use.

Nichols does not explain what is feminine about the Magician,

or why ambivalence is especially feminine. Yet it is true that the

side-show trickster of the Marseille Bataleur has a more obvious ambivalence

than Waite’s image. He tricks us with his constant motion and patter, designed to distract us, but that reminds us that appearances can be

deceiving in other ways. The truth that the Bateleur hides from his audience

from is not necessarily evil in itself: it is merely what in the psyche

ego-consciousness has repressed because it can lead to evil results, for example if he bets others to outwit him in the ball (or shell) and cups game. His focusing ability, getting the audience to focus where he wants them to, is precisely what hides the truth. Notice also the Bateleur's glance to the side, as though he is on the lookout for the law, so he can beat a hasty retreat if need be.

Jung in several places relates the dream of a young theology student. In it, a king decides he wants to be buried in the most splended tomb of his realm. He has the bones of its occupant removed, a virgin of long before. The bones transform themselves into a black horse that runs into the desert, an evil place where his White Magician (wearing a black

robe) declines to go, focused on good. A Black Magician (wearing a white robe) follows the horse and thereby finds the "keys to the kingdom," but does not know what to do with them (just as Jung did not to do with the black wand he was given). Only the White Magician knows that. [77] It takes both, separately and together, like the alchemist's separatio and coniunctio.

The problem with the Waite Magician is that with his focus on the good coming from on high, the repressed stays repressed. And that is where the libido can be revived. In fact, the repression is intensified as the pure white light is directed downward. Jung refers to Plato’s allegory of the charioteer (Phaedrus 253c-254e), in which it is the charioteer’s ignoble horse, the passions acting against all his noble instincts (the charioteer’s noble horse), that drags the Charioteer to the object of beauty. There the charioteer and the noble horse together prevent the ignoble horse from satisfying his lust; yet in the same instant, the charioteer remembers the vision of true Beauty he had had before birth in the upper world but forgot. We are not that far in the tarot sequence yet (for details, see my post on the Chariot card). In the dream, the black magician who finds the keys corresponds to Plato's ignoble horse, and the white magician to the noble horse who supports the charioteer's vision.

With tarot cards, there is the claim that they are a means of divination (cartomancy = divination by cards) where the diviner, the “reader," can supposedly say from the cards, without knowing somone, what has happened, is happening, and will likely happen, in relation to a personal question they have posed, in a way that can move them forward. Is the tarot reader a magician?