This post was completed Sept. 27, 2018, with a few modifications in Dec, 2021 and Dec. 2022.

With few exceptions, this card has always been called Temperance. One exception is in the list given by Alciato, 1544, where it is called Fama, fame, on which more later. Another is an anonymous writer in c, 1565 Central Italy, who speaks of "virtue of the soul" in the place where Temperance would be, but calls it "Prudence." These will be discussed in the appropriate place.The earliest versions of the card are so similar to those of the 18th and 19th centuries that we might think that the card always showed a lady or angel pouring from one vessel to another. But that is not quite true. There is also a tradition in which no lower cup is visible, most of the time with flames on that side of the lady.

In most of the early lists, the card is somewhere after the Pope and before the Wheel. The exception is in the lists of Milan and the numbered cards of France, where she is invariably between Death and the Devil. This exception may or may not have influenced the meaning attached to the card.. So there is plenty to discuss.

1. How temperance was conventionally represented

A woman pouring water from one vessel into another is one medieval image for Temperance In one early case, in an early 11th century illuminated French sacramentary, the jugs are simply held (at left below, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, Ms. Lat. 9436, fol. 106v, detail, reproduced from Adolph Katzennellenbogen, Allegories of the Virtues and Vices in the Medieval Art from Early Christian Times to the Thirteenth Century, trans. Crick, 1964, Fig. 34). Another example is on the tomb of Pope Clement II (d. 1047) in Bamberg Cathedral, Germany (below right) Quite typical of this type is how the water defies gravity, or else is somehow being forced out of one jar, as though from a hose under pressure.

Yet in other cases the water is presented realistically, as in the relief below, of 14th or 15th century Milan, now in the Sforza Castle Museum (author's photo). Temperance is the second lady from the left. She is preceded by Justice and followed by Prudence and Fortitude.

The Cary Sheet version of the card, which is thought to be from either Milan or eastern France of around 1500, has a similar portrayal. As we will see, such realism is the exception rather than the rule.

What could the contents being poured have been thought to be, such that it represents the virtue Temperance? Katzenellenbogen describes 11th and 12th century representations of the virtue as "mixing water with wine", so that "the virtue reduces the over-potent drink to moderate strength" (Ibid., p. 55). Temperance is thus associated with moderation. But why wine and water, as opposed to, say, cold water and hot?

Wine in ancient times was apparently quite concentrated and needed to be diluted. Wine in moderation was thought to promote good feelings between people. However

too much wine was considered harmful. Among the Greeks and Romans, this teaching was incorporated into the myth of Dionysus, also called Bacchus, god of wine. Vincenzo Cartari in his Images of the gods of the ancients, 1581, related (p. 327 of Mulryan translation):

As Athenaeus tells us, the very first person Dionysus taught to mix water with wine was the Athenian king Amphitryon, which was really a great service to humanity.The source appears to be Athenaeus's Deipnosophists, 2.38. Earlier, Cartari described the benefit of wine (p. 326):

drinking moderately enlivens men's spirits, and makes them happier and more daring; it is even supposed to sharpen their mental faculties. This is why the ancients made Bacchus the leader and guide of the Muses, like Apollo.Drinking to excess, however, was harmful (Ibid.):

wine and drunkenness often expose something that someone had taken great pains to conceal, hence it was said proverbially that 'there is truth in wine"Another reason is shown by contrasting ways of depicting Dionysus (p. 329):

He wore a long beard and looked very stern in one, but he had a happy face and looked very young and soft in the other. The first one tells us that the immoderate use of wine makes men frightful and incensed, the second that the temperate use of wine makes us joyful and happy.

The source here is Diodorus Siculus, a text not known until the 15th century, but the point is obvious enough. People when drinking to excess get into drunken brawls. They also commit sexual indiscretions that might result in retaliation by others. Cartari reports that for the ancient medical writer Galen, wine in excess, also accelerated aging; I will give the relevant quote later.

It is possible that the image was also interpreted as mixing cold water

with hot, so that the liquid in the lower cup will not burn the one who

drinks from it or cause discomfort. But the water vs. wine

interpretation is surely paramount, because of the wide literature on

this subject both Greco-Roman and Christian (more on the latter later).

Either interpretation

might be suggested by the colors on the lady's dress in the d'Este card,

with blue on top, for water and cold, and red on the bottom, for wine and heat (below center, c. 1473). However

this color schema is reversed on the Visconti-Sforza card (late 15th century) and on French

cards thereafter (second row below, excluding the one on the left: Noblet, c. 1660s Paris; Chosson, 1672 or 1735, Marseille). Also, another hand-painted card, this time from Florence, c. 1460, has green (top row right). It may well be that the colors have no symbolic significance.

While the colors of the Visconti-Sforza (1470s-1480s?) and d'Este (middle above, 1480s?) are similar, if differently applied, what links the d'Este with the Charles VI (right, 1460s-70s?) is the polygonal halos. This was a peculiarly Italian tradition used for allegorical figures. Other examples, besides the Fortitude, Temperance, and World cards of the Charles VI, are the Seven Virtues and Seven Liberal Arts on wedding chests by Dal Ponte, Florence 1430-1435, and Triumphs of Fame by Pesellino (c. 1450) and Apollonio del Giovanni (c. 1449), also on Florentine wedding chests, so perhaps both the d'Este and Charles VI were Florentine productions.

A feature of the d'Este card is the figure's crossed legs. About a similar posture on Durer's Sol Iusticia, 1553, Panofsky comments (Durer, p. 78):

A nimbed man with the attributes of Justice, a pair of scales and a sword, is seated on a lion patterned after those which Durer had sketched in Venice (909, fig. 57, and 1327). The crossed legs also refer to the idea of Justice; this attitude, denoting a calm and superior state of mind, was actually prescribed to judges in ancient German law-books.

While crossed legs also fit the image of Justice, Temperance, too, requires a "calm and superior state of mind."

The virtue of Temperance was also depicted in other ways besides that of a lady pouring from one vessel to another. One such, as old as Giotto,

c. 1306, (Scrovegni Chapel, Padua) associates her with a bridle, i.e. the restraint that the

virtue demands (detail, below left). Giotto puts it in her mouth; alternatively, as with Raphael, 1511, she dangles it from one hand (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardinal_and_Theological_Virtues_(Raphael)).

Another way of portraying Temperance was by associating her with some instrument for telling time. In the Palazzo Publica of Siena, a fresco by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, c. 1339, has her holding an hourglass (below left, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ambrogio_Lorenzetti_002-detail-Temperance.jpg). This was turned into a clock in Parisian representations, which we start seeing in an illumination of Temperance accompanying Christine de Pisan's Épître d’Othéa.ca. 1406, Paris (center below, online in Gallica, 2v there, based on a drawing by the author), where she is adjusting the wheels of a clock. In an illumination of c. 1430 (I have lost track of the source), she has both the clock and the bridle, and a calipers as well. Considering also the calipers, it probably relates to Temperance's measured way of regulating behavior, neither too much one way or the other.

These alternative attributes of

temperance do not seem to have impacted the imagery of this tarot

subject.But another way of depicting temperance may well have influenced at least a few examples down through the centuries. You might have noticed Cupid holding a torch, symbolizing the fire of desire ("holding a torch", we say of someone who can't let go of an impossible love). That torch was part of the iconography of temperance since the early Middle Ages, as for example the one on the near left, which is from the 9th century, where a lady in a halo holds a torch in one hand and a pitcher, presumably containing water, in the other (Autun, Bibliotheque Municipale, MS. 19, fol. 173v, detail, online at http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/public/mistral/enlumine_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_98=POSS&VALUE_98=%27Raynaud%27&DOM=All); the other, far right, with Fortitude, is 14th century, British Library Arundel Ms. 83 I, fol. 129, detail, reproduced from The Psalter of Robert de Lisle in the British Library, by Lucy Freeman Sandler). This manner suggests the power of temperance to quench the fire of the passions, in particular the fire of sexual desire and perhaps of anger.

These alternative attributes of

temperance do not seem to have impacted the imagery of this tarot

subject.But another way of depicting temperance may well have influenced at least a few examples down through the centuries. You might have noticed Cupid holding a torch, symbolizing the fire of desire ("holding a torch", we say of someone who can't let go of an impossible love). That torch was part of the iconography of temperance since the early Middle Ages, as for example the one on the near left, which is from the 9th century, where a lady in a halo holds a torch in one hand and a pitcher, presumably containing water, in the other (Autun, Bibliotheque Municipale, MS. 19, fol. 173v, detail, online at http://www.enluminures.culture.fr/public/mistral/enlumine_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_98=POSS&VALUE_98=%27Raynaud%27&DOM=All); the other, far right, with Fortitude, is 14th century, British Library Arundel Ms. 83 I, fol. 129, detail, reproduced from The Psalter of Robert de Lisle in the British Library, by Lucy Freeman Sandler). This manner suggests the power of temperance to quench the fire of the passions, in particular the fire of sexual desire and perhaps of anger.In one deck, anonymously printed in Paris around the beginning of the 17th century, this theme is expressed without a torch but with clearly visible flames on the ground. While later decks prefer another jar to flames, that it is on the ground suggest to me the influence of the earlier depiction. I will discuss the "Sol Fama" motto on the banners a little later.

In what seems to be a very early version of the water on flames motif, a card of one deck (called the Catania, from where most of the cards are kept, or sometimes the "Alessandro Sforza", perhaps as early as 1445, or as late as 1475), shows a lady pouring water onto what might simply be his or her sex. No lower vessel is apparent. Michael Dummett, who surely examined the actual card, described it this way (in Il Mondo e l'Angelo, 1993):

una ragazza nuda, reclina su di un cervo, con una collana di corallo. Nella mano sinistra regge un oggetto che, essendo dipinto in oro su fondo d'oro, è di difficile identificazione; nella destra, sollevata sulla sinistra, regge un altro oggetto, anch'esso dipinto in oro su fondo d'oro, che, come il primo, sembra essere un vasoIt seems to me that she might be holding a candle or torch. Andrea Vitali, who has also seen the original (personal communication) attests that she is not holding anything, and that the water is being poured on her sex. For myself, I am not even totally sure it is a woman, because painters, at least in Florence at that time, did clearly male examples with such pectorals, notably Lo Scheggia (left below, the inside lid of a marriage chest) and Apollonio da Giovanni (right below, from a c. 1450 illuminated Aeneid in the Biblioteca Riccardiana, Florence, as identified by Emilia Maggio in her article, "The Star Rider from the so-called 'Alessandro Sforza' Tarot," online in Academia). An assignation to Florence is suggested not only by these figures but by the other surviving cards of this deck, which are quite similar to the corresponding cards in another deck thought to be Florentine, the so-called "Charles VI". In any case, everyone agrees that the subject is Temperance; the direction of the water's flow suggests the same message as that of the earlier images with a torch, that temperance douses the ardor of lust.

(a naked girl reclines upon a deer, with a coral necklace. In her left hand she holds an object which, being painted in gold on a gold background, is difficult to identify; in her right, raised above on the left, she holds another object, also painted in gold, on a gold background, which, like the first one, seems to be a jar.)

The animal that the figure is

sitting on also needs to be taken into account. Everyone agrees that it is a stag, but what is its

significance? Marco Ponzi on Tarot History Forum points to a 16th century painting by

Cranach of Diana sitting on a deer while her brother Apollo looks on.

Diana, goddess of the hunt, was frequently shown with deer, either

shooting them or having them as pets. Diana was well known as one of the

virginal goddesses of the Greco-Roman pantheon (with Athena and

Vestia). That she can sit on the deer further indicates her taming of animal desire (even if the deer was considered a mild animal).

The animal that the figure is

sitting on also needs to be taken into account. Everyone agrees that it is a stag, but what is its

significance? Marco Ponzi on Tarot History Forum points to a 16th century painting by

Cranach of Diana sitting on a deer while her brother Apollo looks on.

Diana, goddess of the hunt, was frequently shown with deer, either

shooting them or having them as pets. Diana was well known as one of the

virginal goddesses of the Greco-Roman pantheon (with Athena and

Vestia). That she can sit on the deer further indicates her taming of animal desire (even if the deer was considered a mild animal).There is a further symbolic function of the deer relevant to the card just shown. The deer was a symbol of "longing for God", using an image from the beginning of Psalm 42:

As the hart panteth after the fountains of water; so my soul panteth after thee, O God.(For an illustration of this line, see below right, from Richard de Fournival, Bestiaire d’amour, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, fr. 1951, f. 13v, 13th-14th century). Thus the action of the water on the card, and the practice of Temperance, might well be to move one closer to God, with the deer the symbol of that movement. Temperance serves to redirect one's longing, from bodily desires to spiritual ones. The deer on the card is carrying the person or god in the direction of this longing, following its thirst.

Both Diana in the Cranach and the card's person reclining on the deer wear a coral necklace. This was a commonly worn also by the Christ child in Madonna and Child paintings; its red color would likely be a reminder of his future sacrifice (the one below is from 1360, by Allegretto Nuzi, currently in the Petit Palais Museum, Avignon). It was also worn by children as protection against disease. What it means in the context of Diana is something of a puzzle. It might indicate purity or her role as protector of women in childbirth. For those who still die, it might suggest a parallel with Christ; just as his sacrifice gives life, so does the mother's, should she die giving birth, a major danger up until the 20th century. .

It is worth asking why just two of the ways of depicting Temperance seem to have impacted the tarot and not the others. I will address that question later.

2. The allegory in relation to its position in the sequence

In the so-called "A" or "Southern" order of the tarot sequence (Florence, Bologna, later Rome and Lucca), the card was placed immediately after Love, followed by Fortitude and Justice. This order corresponds to the relative importance of the three parts of the soul, in the Platonic tradition: temperance for the part of the body below the lungs (stomach, kidneys, liver, sexual organs), fortitude for the lungs and heart, and justice (with wisdom or prudence) for the brain. These were the primary virtues needed for a successful marriage and life in society (the latter symbolized by the chariot).

It is probably for this reason that some tarots even put Temperance before the Love card, because it was necessary for the proper conduct of love. A similar point could be made for the virtue of Fortitude, as necessary for the attainment of the victories symbolized by the Chariot card.

An Italian essay on the tarot written anonymously about 1565 is of this sort. Between the cards representing the temporal and spiritual powers (he calls them King, Emperor, Cardinal, and Pope) and those of Love and Chariot, he says, are Prudence and Strength, the one a virtue of the soul and the other of the body (in con il occhi e con l'intelletto: Explaining the Tarot in Sixteenth Century Italy, ed. and trans. Caldwell, Depaulis, and Ponzi, 2018, p. 55)

Seguita poi la Prudenza in ordine et la fortezza la prima virtu dell' animo, l'altra del corpo; et da molti estremamente desiderate.By Prudence, he is probably referrng to the Temperance card, which counsels prudence in matters having to do with the body, including in this case Strength.

In the order Prudence follows, then Strength. The first is a virtue of the soul, the second of the body and they are much desired by many.

In the "B" order of Ferrara and Venice, which this author follows, Justice appeared as the next to highest card, thus God's justice rather than man's. The other two virtues were situated after Love and before the Wheel of Fortune, Fortitude first.

Despite what the anonymous tarot writer says about temperance being a virtue of the soul rather than the body, traditionally, from the time of Plato and Aristotle, temperance was considered as primarily aimed at excesses in the bodily appetites of sexuality, drinking, and eating. Plato said that temperance was about control over the appetites, of which he mentioned food, drink, and sex ("concupiscence), those which adults share with children and which dominate the lives of the "inferior multitude" (Republic Book IV, 431).

Aristotle said something similar, first that temperance had to do with bodily pleasures rather than pleasures of the soul or spirit, and specifically those having to do with the sense of touch, namely, eating, drinking, and sex, for which someone inordinately concerned was termed "brutish", likening him to the animals (Nichomachean Ethics Book IV, Ch. 10). Unlike other virtues, however, the danger with temperance had mainly to do with excess rather than deficiency; people did not have to strive to overcome the urge to avoid alcohol, food, or sex. In fact, it was even considered virtuous to avoid sex and alcohol, as any amount entailed a certain loss of self-control: "the man who abstains from bodily pleasures and delights in this very fact is temperate", Aristotle said (Ibid, II-3). It is only the person who shuns all pleasures that Aristotle singles out for vice: "Persons deficient with regard to the pleasures are not often found; hence such persons also have received no name. But let us call them 'insensible"' (Ibid. II-7). But even "insensibility" is not much of a vice.This perspective of course was continued under Christianity, if anything even more than before.

St. Thomas Aquinas, whose ethical thought dominated 15th century Italy, was similar. After first distinguishing fortitude as primarily about dealing with fear and temperance as about dealing with desires, Aquinas says (Summa Theologiae II-II, q.141, a. 4)

Now fortitude is about fear and daring with respect to the greatest evils whereby nature itself is dissolved; and such are dangers of death. Wherefore in like manner temperance must needs be about desires for the greatest pleasures. And since pleasure results from a natural operation, it is so much the greater according as it results from a more natural operation. Now to animals the most natural operations are those which preserve the nature of the individual by means of meat and drink, and the nature of the species by the union of the sexes. Hence temperance is properly about pleasures of meat and drink and sexual pleasures.He did not deny that temperance also had to do with self-control over desires in other areas of life, but that was in a broader sense.

If so, how does it happen that in the Milan order it appears not only last ,which could be explained as pertaining to the lowest part of the soul), but more oddly after the Death card? The dead surely are in no need of Temperance, as a virtue governing food, drink, and sexuality, all notable for being physical pleasures.

For one thing, temperance as the proper treatment of the body, neither excessive nor deficient, could mean a longer life. Cartari in discussing a statue of Dionysus (Mulryan trans., p. 326):

... the statue ... portrayed Bacchus as a bald-headed old man who was almost hairless. This statue also showed that ... drinking hastens the aging process, and that men in that age group drink a great deal. We get old only after we start to lose our natural moisture, which we try to replace with wine. But we often deceive ourselves, for although wine is inded moist, in its essence and power it is so warm that instead of increasing moisture it dries it up and drains it away. For as Galen remarks about heavy drinkers, the more they drink to quench their thirst and eliminate it, the more it increases, and the bigger it gets.The editor directs us to Macrobius, Saturnalia 7.6.19 and Athenaeus on Galen, Deipnosophists 1.26C.

And of course there was the danger of death from getting into fights, as well as from secrets we might reveal when under the influence, From lack of inhibition, there is also the danger of adultery and other sexual indiscretions that could cause retaliation from others. Thus it can defeat death temporarily

Francesco Piscina, in his Discorso of 1565, makes a different point(Caldwell et al p. 22-23),

Then Temperance comes, a most beautiful virtue that moderates us in the pleasures of the body, according to the law, and that can here be interpreted as any other virtue, that does not fear the strikes of Death, nor the inconstancy of Fortune: on the contrary, virtues make men and immortal, according to the opinion of the Poet, they take the man out of the grave and preserve him for a long and immortal life.The Poet in question is Petrarch, the editors explain in a note, in his "Triumph of Fame", the part of his "I Trionfi" that came after the "Triumph of Death". That after Death Petrarch put Fame perhaps explains why Alciati called the card "Fame" and why "Sol Fama" (Only Fame) was on the Temperance lady's banner in the Vieville of c. 1650 Paris and the Flemish decks of the 18th century. But where Petrarch says that Fame takes a man out of the grave for a while, and his fame will eventually be overcome by Time, Piscina is affirming that it is Virtue that defeats Death, and that Virtue gives immortatlity. That is a more extreme claim, but justification enough for putting Temperance, as the last of the three main moral virtues, as triumphing over Death and so after that card in the order.

But according to Christian belief it was not just virtue that was required for immortality, but also a commitment to Christ, as manifested especially in the taking of Holy Communion. Since the mixing of water and wine was part of the rite of Communion, that is another way the lady on the card could symbolize victory over death. On this point Aquinas gave four reasons for this custom (Ibid, Part III, question 74, article 6):

Water ought to be mingled with the wine which is offered in this sacrament. First of all on account of its institution: for it is believed with probability that our Lord instituted this sacrament in wine tempered with water according to the custom of that country: hence it is written (Proverbs 9:5): "Drink the wine which I have mixed for you." Secondly, because it harmonizes with the representation of our Lord's Passion: hence Pope Alexander I says (Ep. 1 ad omnes orth.): "In the Lord's chalice neither wine only nor water only ought to be offered, but both mixed because we read that both flowed from His side in the Passion." Thirdly, because this is adapted for signifying the effect of this sacrament, since as Pope Julius says (Concil. Bracarens iii, Can. 1): "We see that the people are signified by the water, but Christ's blood by the wine. Therefore when water is mixed with the wine in the chalice, the people is made one with Christ." Fourthly, because this is appropriate to the fourth effect of this sacrament, which is the entering into everlasting life: hence Ambrose says (De Sacram. v): "The water flows into the chalice, and springs forth unto everlasting life."

The first reason has already been discussed in relation to Cartari on Dionysus, and the reasons for this custom, essentially to reduce the chances of excess consumption. .

The first reason has already been discussed in relation to Cartari on Dionysus, and the reasons for this custom, essentially to reduce the chances of excess consumption. .A Renaissance image of the second reason, that of bringing to mind the two liquids flowing from Christ at the crucifixion, is by Albrecht Durer, 1516, at right.

The third reason, the symbolic one of water representing the people and wine Christ, goes back to Clement of Alexandria, 200 a.d. who said. “As wine is blended with water, so is the Spirit with man.” Likewise St. Cyprian a few years later: “The water is understood as the people while the wine shows forth the blood of Christ".

The fourth reason, that of symbolizing the transformation from mortality to immortality,was typified by the miracle at Cana, where Jesus replenished the wedding's wine supply by

instructing the steward to fill the wineskins with water, after which

the contents were found to be the most delicious wine. Such a scene is

pictured in the early 16th century painting The Marriage of Cana by a follower of

Hieronymus Bosch, in a way that has all the elements of the tarot card.

The fourth reason, that of symbolizing the transformation from mortality to immortality,was typified by the miracle at Cana, where Jesus replenished the wedding's wine supply by

instructing the steward to fill the wineskins with water, after which

the contents were found to be the most delicious wine. Such a scene is

pictured in the early 16th century painting The Marriage of Cana by a follower of

Hieronymus Bosch, in a way that has all the elements of the tarot card. There is a Greco-Roman precedent for the wine of immortality, namely the nectar that the gods drank to renew their immortality, typically poured by Ganymede but in the days before Hebe became Hercules' wife, she was the one who poured, and she did so occasionally even after her marriage. The late Roman Empire writer Nonnus says (my emphasis):

All the inhabitants of Olympos were sitting with Zeus in his god-welcoming hall, gathered in full company on golden thrones. As they feasted, fairhair Ganymedes drew delicious nectar from the mixing-bowl and carried it round. For then there was no noise of Akhaian war for the Trojans as once there was, that Hebe with her lovely hair might again mix the cups, and the Trojan cup-bearer might be kept apart from the immortals, so as not to hear the fate of his country." [N.B. During the Trojan War, Ganymedes became distressed, and so Zeus had Hebe temporarily resume her former station as cup-bearer of the gods.] (http://www.theoi.com/Ouranios/Hebe.htm)

She

was also famous for having a shrine where escaped slaves and prisoners

could go, pray to the goddess, and win their freedom. The ancient Greek travel writer Pausanias, writing

about this shrine, says:

She

was also famous for having a shrine where escaped slaves and prisoners

could go, pray to the goddess, and win their freedom. The ancient Greek travel writer Pausanias, writing

about this shrine, says:

Of the honors that the Phliasians pay to this goddess the greatest is the pardoning of suppliants. All those who seek sanctuary here receive full forgiveness, and prisoners, when set free, dedicate their fetters on the trees in the grove. (http://www.theoi.com/Ouranios/Hebe.html)

This story is also cited in Cartari, 1581 (Mulryan trans. p. 45, with a picture (from http://www.uni-mannheim.de/mateo/ca...1/jpg/s038.html). In the illustration it appears that she holds a cup in one hand and either a cup or a bowl in the other. You can see the prisoners' fetters hanging from the trees. She has the power to forgive of sins, Cartari tells us. Since that is what the Eucharist is about, it would make sense to put her on the card, if that is one meaning of the scene there.

If the lower vessel is earthen, and also the water in it, adding water from above might also have suggested an aspect of the myth of Isis and Osiris. Isis represented the land of the Nile Valley drained of nutrients by the previous crops, while Osiris was the personification of the Nile flood, a summer torrent from the Ethiopian highlands which would revitalize the soil, renewing it for another planting season. Plutarch even describes a ritual in Egypt where water and earth were mixed, with the purpose of ensuring a good flood.

A s Plutarch told the tale in "On Isis and Osiris", Osiris was the personification of good and Typhon the same for evil.

In Egypt there are statues and tomb inscriptions showing the Pharaoh

accepting both of the rival gods, Horus and Typhon. From Plutarch's perspective, it is the mixing of good and evil. In the myth, when Horus, Osiris's son, captures Typhon and brings him to Isis for execution, Isis lets him go, as though recognizing that both good and evil are necessary. In one tarot, that of Dodal (Lyon 1701-1715), the angel mixing the contents of the two jars is dressed in a way that suggests the classic

Egyptian style for women, with much neck adornment but exposed breasts (or flesh-colored fabric). It is as though Dodal were showing us Isis supporting both the evil Typhon and the good Horus.

s Plutarch told the tale in "On Isis and Osiris", Osiris was the personification of good and Typhon the same for evil.

In Egypt there are statues and tomb inscriptions showing the Pharaoh

accepting both of the rival gods, Horus and Typhon. From Plutarch's perspective, it is the mixing of good and evil. In the myth, when Horus, Osiris's son, captures Typhon and brings him to Isis for execution, Isis lets him go, as though recognizing that both good and evil are necessary. In one tarot, that of Dodal (Lyon 1701-1715), the angel mixing the contents of the two jars is dressed in a way that suggests the classic

Egyptian style for women, with much neck adornment but exposed breasts (or flesh-colored fabric). It is as though Dodal were showing us Isis supporting both the evil Typhon and the good Horus. 17th century France may not have known the images of Pharaoh embracing the two opposites. But they would have read in Plutarch about the mixing of the two principles, Osiris and Seth, good and evil. In explanation Plutarch quotes Euripides: “Evil and good cannot occur apart; There is a mixture to make all go well.” In Noblet's day people would have also known this principle from Montaigne, in one of the last things he wrote (Essays, Book III, "On Experience," trans. Frame, 1958, p. 835, in Google Books, originally 1587-1588):

Our life, like the harmony of the world, is composed of contrary things, also of diverse tones, sweet and harsh, sharp and flat, soft and loud. If a musician liked only one sort, what effect would he produce? He must be able to use them together and blend them. And so must we the good and the evil which are consubstantial with our life. Our being cannot subsist without this mixture, and one group is no less necessary to it than the other.It is through the accomplishment of good in the face of evil that good shines. In fact, without this opposition, it would no longer be good, but simply the unimpeded satisfaction of desire, like the eating of the trees of Paradise if there were not one that was forbidden.

being attracted to this life by the imagination and vital power simultaneously, then the rational soul, in a way contracts. Moreover, it acquires under heaven a more contracted body, that is, an airy body, until, having contracted still more, it descends into the most contracted body of all, the earthy. Everywhere it is principally named man, but in heaven, celestial.man; in the air, airy man; and on earth, earthy manHere he is bringing to bear the teaching of Plotinus in his fourth Ennead, chapter Three, section 15 (http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/plotenn/enn301.htm):

The souls peering forth from the Intellectual Realm descend first to the heavens and there put on a body; this becomes at once the medium by which as they reach out more and more towards magnitude [physical extension] they proceed to bodies progressively more earthy.Plotinus in the above passage does not name the airy body as such, but only bodies "progressively more earthy". However earlier in the same chapter, at 4.3.9 he speaks of "a soul leaving an aerial or fiery body for one of earth".

And when Lachesis [one of the Fates] has no more thread to draw, the soul frees itself from the flesh, taking both the human and divine powers: the other faculties falling silent: memory, intellect, and will far keener in action than they were before. It falls, by itself, wondrously, without waiting, to one of these shores: there it first learns its location.Although he does not use the term "body" specifically, to indicate the form that the soul prints on the air, what he says is close in meaning to Ficino's conception of the "airy body."

As soon as that place encircles it, the formative power radiates round, in quantity and form as in the living members: and as saturated air displays diverse colours, by the light of another body reflected in it, so the surrounding air takes on that form that the soul, which rests there, powerfully prints on it: and then, like the flame that follows fire wherever it moves, the spirit is followed by its new form.

Since it is in this way that it takes its appearance, it is called a shadow: and in this way it shapes the organs of every sense including sight. In this way we speak, and laugh, form tears, and sighs, which you might have heard, around the mountain. The shade is shaped according to how desires and other affections stir us, and this is the cause of what you wondered at.

In this framework we may imagine one vessel as the earthy body, and the other as the airy body, with the soul as the liquid between them. Given that the earthy body is lower than the airy body, this interpretation gives the odd result that the liquid flows upward, defying gravity. In its airy body, the soul can either stay where it is, haunting the earth, or rise higher.

There is some suggestion of this passage on the card, namely the way the liquid between the two vessels defies gravity, both in the tarot and in one form of its medieval representations. It can be explained as the soul, which has no weight, floating between two bodies. Its elongation is also reminiscent of a bridge between two sides of a stream. Rivers often formed the boundaries of actual countries, and likewise streams for individual landholdings. So bridges symbolically represent the passage from one realm to another, in art. It was the same function as gates, for example the gate of St. Peter to heaven. Examples are in two paintings by Hieronymus Bosch, early 16th century Flanders; one has a gate and the other a bridge. In the first case, a closed gate greets the wayfarer who has led a riotous life; in the other, a rickety bridge suggests a possible passage to the next realm..

3. The Lady Sprouts Wings

Hermes is a god and has wings and flies, and so do many other gods. First of all, Nike (Victory) flies with golden wings, Eros (Love) is undoubtedly winged too, and Iris is compared by Homer to a timorous dove.

For Iris, goddess of the rainbow, we have Virgil in the Aeneid (9.2, quoted at https://www.theoi.com/Pontios/Iris.html):

Soaring to heaven on balanced wings, [Iris] blazed a rainbow trail beneath the clouds as she flew . . . Iris, glory of the sky, cloud-borne.

There is also Christianity's co-option of winged gods and goddesses as angels. Dark angels bear one to hell, light angels to heaven. Wings are versatile instruments. They can also take one from one place on earth to another, as for example the woman of Revelation 12, who was given wings so as to flee the beast and escape into the wilderness.

In the Neoplatonic scheme, the presence of wings would correspond to the transition from the earthy body to the airy body. Wings function in the air, or something like the air. If the soul is still attached to earthly things, it will not fly very high. But in Plato's Phaedrus, the chariots of the gods have winged horses, and so d the soul of mortals until it descends to earth. With the exercise of temperance, in the sense of the replacement of physical sexuality with friendship, the wings grow back, in his allegory, and those who succeed are able to ascend to heaven. Plato writes of such lovers (256B, p. 65 of Walter Hamilton translation):

In surviving Florentine representations, it was the charioteer rather than the horses that were pictured as winged at this stage, for example on the pendant of a sculpture attributed to Donatello of a boy, thought by some to memorialize a son of Cosimo de' Medici who died early in life. That the chariot is ascending to heaven is clear from the direction in which the horses are moving.So, if the higher elements in their minds prevail, and guide them into a way of life which is strictly devoted to the pursuit of wisdom, they will pass their time on earth in happiness and harmony; by subduing the part of the soul that contained the seeds of vice and setting free that in which virtue had its birth, they will become masters of themselves and their soulswill be at peace Finally, when this life is ended, their wings will carry them aloft...

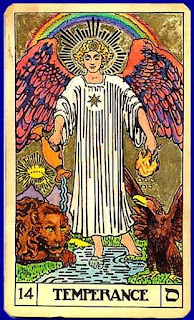

4. De Gebelin and the 19th-20th century occultists

De Gebelin's analysis of the card is no departure from tradition: "It is a winged woman who pours water from one vessel to another, in order to temper the liquor it contains" (trans. J. Karlin in Rhapsodies of the Bizarre, p. 23, p. 372 of original, Le Monde Primitif, vol. 8, in Gallica). His co-author de Mellet says a little more, to show a connection to the card before (Ibid., p. 52. p. 398):

Fourteenth, the angel of Temperance comes to educate man, to make him avoid death to which he is now condemned. he is depicted pouring water into wine. to show him the need for watering down this liquor, or for moderating his affections.It is again to avoid death and has to do with the appetites.

Etteilla explicitly departs from this previous consensus to make it more general. Naturally, he attributes this understanding to the Egyptians (my translation from his Troisieme Cahier [Third Notebook], 1785, original in Gallica):

Temperance signifies or announces that one must be temperate in the habits relating to the subject indicated in the card, be they physical or moral, for the extremes, in one and the other case, are contrary to human reason, also to the law that wise nature indicates for us, in its movements generally.This connection to prudence is not new; we have seen it in the "Anonymous Discourse."

The Egyptians considered Temperance differently than we; they did not say that it had to do more directly with our carnal passions, than with all our vices; some lines in the book of Thoth, written because of this, will put us in a position to judge.

Temperance is a virtue which rules morality as much as physicality; it is called the precursor of the truth; without temperance, man bears all the other virtues in a period which degenerates them [i.e. without temperance, in time its lack will degenerate them]. Of a man who would be virtuous, intemperance makes him a maniac, an enthusiast, a dullard; thus for strong reason, how much temperance is necessary, generally, in all our vices, our blind passions, our faults, our weaknesses, our infirmities, and also in the brute things utilized in the physical life of man.

Temperance recommends chastity in virginity, marriage and widowhood; it oversees continence, clemency, modesty, study, affability (leniency, gentle, easy, tractable and thoughtful), misery, humility, moderation, simplicity; it is the mistress of ambition, curiosity, luxury, play, drunkenness, self-esteem, and finally all the vices, as prudence warns of them, and strength surmounts them.

Etteilla also has a unique way of picturing the lady with the jugs, with one foot on a sphere and the other on a flat slab. Here he is borrowing from a Renaissance way of juxtaposing that which swiftly goes away, i.e. opportunity, with that which is long-lasting, i.e. wisdom, using the characteristic motion of the two solids: the sphere to roll easily, the slab to move with great difficulty. The school of Mantegna, 15th century, depicted the two as such in a work that showed a youth grasping at opportunity but being restrained by wisdom. The conventional title is Occasio and Poenitentia, i.e. "Opportunity and Second Thoughts." Temperance is between the extremes; like someone who acts with due speed, neither too quickly, like the sphere, nor too slowly, like the slab.

A second version of the Etteilla card had a lady without wings but with an elephant and a bridle. The bridle is the instrument by which the animal, and thus its instincts, are restrained. The elephant, meanwhile was famous for its chastity. In a popular manual of piety called Introduction to the Devout Life, by St. Francis of Sales in 1609, ch. 39 par. 7, we read, as translated from the French (quoted at http://faithmag.net/faithmag/column2.asp?ArticleID=774/):

Another belief about the elephant was that it never overate. Ripa says, as Andrea Vitali quotes his Iconologia at http://www.letarot.it/page.aspx?id=126:The elephant is not only a huge beast, but the most dignified and most intelligent animal which lives on earth. I wish to tell you an instance of its excellence. It never changes its mate and loves tenderly the one it has chosen. However, it does not mate with it except every third year, and that for five days only, and so secretly that it is not seen doing the act. Nevertheless, it is seen on the sixth day on which, before anything else, it goes straight to the river. There it washes completely its whole body without any wish to return to the flock before it is purified. Are not these beautiful and chaste characteristics of such an animal an invitation to the married?

L’elefante è posto per la Temperanza, perche essendo assuefatto da una certa quantita di cibo non vuol mai passare il solito, prendendo solo tanto, quanto è sua usanza per cibarsi"A third version of the card (above far right) used an image from the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1495, that kept the bridle and, rather strangely, just one cup.

(The elephant is put for Temperance, as being accustomed to a certain quantity of food, it never wants more than the usual, taking only as much as is its custom in order to feed itself.)

A reinterpreation of the tradition of mixing liquids starts with Eliphas Levi in the 1860s. In his discussion of the card, he says (Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie, 1930 reprint (from 1859), Part II, p. 352, online in Gallica, trans. Waite as Transcendental Magic: its Doctrine and Ritual, p. 368):

LA TEMPÉRANCE, un ange, ayant le signe du soleil sur le front, et sur la poitrine le carré et le triangle du septénaire, verse d'une coupe dans l'autre les deux essences qui composent l'élixir de vieThe sun is one form of philosophical gold, he says at the beginning of Chapter 12 of vol. 2, on the Great Work (Waite trans., p. 264); so the angel must be an adept. Card 14 is the last card of the second septenary, corresponding to the Chariot in the first. This is in a tradition, already stated by de Mellet, of seeing the trumps as divided into three equal sections (gold, silver, and iron: pp. 50-54 of Karlin, pp. 396-400 of original). Levi does not explain what the triangle and square symbolize, but the card of the "first septenary" has on its front a male symbol (the Indian lingam, he says), in a cup, which is surely a female symbol; and in Pythagoreanism 3 is male (odd) and four female (even), making the angel androgynous, as Wirth will say explicitly later. Their sum is seven, of course

TEMPERANCE, an angel with the sign of the sun upon her [or its] forehead and on the breast the square and triangle of the septenary, pours from one chalice into another the two essences which compose the elixir of life.

Otherwise in that chapter 14, entitled "Transmutations," he is concerned mainly about people who become werewolves or are seen in two places at the same time. He says that the werewolf is a product of someone's dream that he or she is a wolf. As for bi-locators, it is either dream or an ecstatic state, as in the case of someone who is seen praying in Spain for the life of the pope and also at said pope's deathbed.

Levi's disciple Paul Christian says (p. 106 of English translation) that this arcanum "expresses in the divine world the perpetual movement of life; in the intellectual world the combinations of the ideas that create morality; in the physical world the combinations of the forces of life." The Angel is the "spirit of the Sun" and the liquid is the "vital sap of life". He adds that "it is the symbol of all the combinations which are ceaselessly produced in all parts of Nature."

Papus (Morton trans. p. 162) affirms both Levi and Christian, but in the manner of an outline, leaving much unclear. For him the arcanum represents

1° Combinaison de fluides différents.The second part seems also referred to when he says "the entry of Spirit [l'Esprit] into matter and the reaction of matter onto [sur = on or upon] Spirit," In that sense it is about incarnation, a rather odd place for it, after death, but not so much before the Devil. Perhaps the idea is that without material form in a particular place and time, individual examples of the same essence are not possible. He adds:

2° Individualisation de l'existence.

1. Combination of different fluids.

2. Individualization of existence.

Le génie du Soleil verse d'une urne d'or dans une urne d'argent les essences fluidiques de la vie.Papus asserts that the figure is a girl, the same as on cards 11 (Strength) and 17 (The Star). This is an expression of his idea that the tarot advances in sequences of three. Moreover,

(The genius of the Sun pours the fluidic essences of life from an urn of gold into an urn of silver.)

Le courant vital situé sur sa tête à l'arcane 11 passe ici d'une urne dans l'autre et s'épandra en 17.

La quatorzième lame du Tarot nous montre les fluides naguère conservés, maintenant en pleine circulation dans la nature

(The vital current on her head with arcanum 11 passes here from one urn to the other and spreads out in 17.

The fourteenth card of the Tarot shows us the fluids hitherto preserved now in full circulation in nature.)

Such circulation is also the "combination des fluides actif et passif" (combination of active and passive fluids). Perhaps that is a reference to wine and water, or sperm and sap.

Such circulation is also the "combination des fluides actif et passif" (combination of active and passive fluids). Perhaps that is a reference to wine and water, or sperm and sap.For A. E. Waite (Pictorial Key to the Tarot, 1909), like his predecessors, the winged figure "has the sign of the sun upon his forehead and on his breast the square and triangle of the septenary." This is simple addition. In this case the triangle seems connected with the rising sun in the background, to which there is a clear path from the angel. To clarify what might be a misapprehension, he adds that this "he" is only a manner of speaking; the angel is actually without gender. Then he adds something new: "He has one foot upon the earth and the other upon waters, thus illustrating the nature of the essences." It perhaps is an affirmation of Papus's idea that individual existence requires matter, represented by earth, and the cups, and not just the life-force, represented by water and fluids generally.

Waite renounces "the conventional meanings, which refer to changes in the seasons, perpetual movement of life and even the combination of ideas." This was Christian's contribution, which Waite finds inept. Finally,

It is, moreover, untrue to say that the figure symbolizes the genius of the sun, though it is the analogy of solar light, realized in the third part of our human triplicity. It is called Temperance fantastically, because, when the rule of it obtains in our consciousness, it tempers, combines and harmonises the psychic and material natures. Under that rule we know in our rational part something of whence we came and whither we are going.Speaking of "our human triplicity" would seem to refer to spirit, soul, and body. The spirit, i.e. our rational part, harmonizes the psychic and material parts. In Plato, this was the function of Justice. Spirit is perhaps what is symbolized by the emblem of the sun on the angel's forehead, with the soul between the two urns, and the earth our materiality.

Of the earlier esoteric interpreters, Oswald Wirth is to my mind the most eloquent. Although Papus said that the angel poured from the golden into the silver, Wirth insists that the silver flows into the gold. Unlike Papus, Wirth also says what they represent (Tarot of the Magicians, 1985, pp. 117-18, with a few corrections based on Tarot des Imagiers, 1927, pp. 169-170, correcting Weiser trans. of):

The jars of precious metal do not correspond to crude bodily containers; they allude to the double psychic atmosphere whose natural organism is only the earthly ballast. Of these concentric containers the one, the nearer (gold, consciousness [conscience, here probably not Weiser's "conscience"] reason) is solar and active; it directs the individual in an immediate way and maintains the energy of the will. The other stretches beyond the first; it is lunar and sensitive (silver). Its domain is more mysterious; it is that of sentimentality, of vague impressions, of the imagination and of the unconscious [inconscient] on a superior level. This ethereal sphere picks up vibrations of the ["the" omitted by Weiser] life common to individuals of the same species, a permanent life which is the reservoir from which we draw the vitality which we individualize. What is concentrated in the silver urn flows into the gold, where condensation is completed with the view to maintaining physical life.This is quite a paragraph. It suggests the ego-self axis of Jung, the connection of the individual consciousness with a collective unconscious which is also the source of our vitality. There are also psychological implications for the healing of the soul (English trans. p. 118, with corrections from French 1927, p. 170):

With our whole being let us feel compassion [compatissons; Weiser: "sympathize"] with all our being for the suffering of others, then exteriorize our affections so as to make for ourselves an environment of love as vast as possible. We will thus benefit from a refractive [i.e. focusing, like the lens of the eye] psychic [animique, pertaining to the soul; Weiser, "life-giving"] milieu, proper for gathering the most ethereal [éthérée; Weiser, "lightest"] vibratory waves, by means of which the true medicine of the Saints and Sages is practiced.In fact, the logic of the situation suggests that without embracing [focusing, refracting] all of humanity in ourselves, we cut ourselves off from the very source of psychic life and will be psychically dead to ourselves and others, like the wilted flower on Wirth's card (which he says Temperance revives). I would wonder if this feeling embrace can be restricted to just our own species, but rather extends to all species and the earth itself. In any case, that is what the silver vessel collects and pours out.

In relation to this life-energy, Wirth observes that (Ibid.):

Strength deploys [déploye; trans. "displays"] devouring activity which would consume the vital Humidity (radical Humidity of the Hermetists), without the refreshing intervention of Temperance. This character restores new sap to the vegetable overpowered by the ripening heat of Leo.This seems to be a reference to September rains, but Wirth, says it is that of Aquarius, which is in opposition to Leo, six months later. In this connection, he also calls it "the angelic cup-bearer of the vital fluid," which will revive the wilted flower on his card. That would seem to refer to the Greek goddess Hebe. Its waters are like the "waters of baptism" from which one is "born again" (Ibid.). As such it corresponds to the alchemical process of repeatedly washing the blackened corpse with the condensed vapors that emanate from it when heated and then cooled, so that it turns gray and finally white.

Without hurrying he seeks the truth, limiting the field of his explorations, careful to keep within the narrow field of human knowledge. For Temperance his reserve is translated into moderation, a negative virtue which spurns extravagance and exaggerations. Moreover, it is a question of practical life rather than abstract speculation. The Initiate who has bathed in the fluid which the solitary Angel pours out is no longer troubled by the fever which shakes ordinary men. Being dead to evil ambitions, to selfish passions, indifferent to the hardships which threaten him, he lives calmly in the sweet serenity of a gentle wisdom, indulgent towards the weaknesses of others.So the action of mixing does more than Waite's "harmonizing of psychic and material forces". It is the conveyance of the life-force itself, which is only effective to the extent the individual separates from his or her own "selfish passions" apart from the collective condition of the world.

With Paul Foster Case, perhaps surprisingly, we are no longer with the tradition of liquid flowing from one vessel to another, but the other traditional depiction of Temperance with a pitcher in one hand and a torch in the other. Moreover, that the water is poured on a lion, an astrologically fiery animal, we are in the company of the 17th and 18th century tarots that showed a lady pouring water on flames at her feet.

At the same time Case continues elements introduced by Waite: the glowing crown on the mountain, the path leading to it, the angel's solar countenance, and its placement of one foot on land and the other on water (Tarot Fundamentals, 1936, p. 1, in archive.org):

On his brow is a solar symbol, and from his head light radiates. One foot rests on water, Symbol of the cosmic mind-stuff. The other foot is on land, symbol of concrete manifestation.In this way even without the pouring of liquid into a cup Case can show the "life-force" or "vital fluid" of the French theorists combining with matter.

the symbol of that, in every human being, to which the term Higher Self is applied. He is not the ONE IDENTITY, but the Life-Breath of that ONE IDENTITY centered in the heart of personality.That life-breath is in continual circulation between the two, the One Identity and the corresponding center of the personality. He is also the Son in Kabbalah, associated with Tifereth on the Tree of Life (p. 2), and the Holy Guardian Angel from whom we receive instruction.

that our personality is not independent, but subject to the action of our Higher Self. Through suspension of the false notion of personal independence one comes to understand the true function of personality as an instrument for the Divine WILL.Then there is the rainbow (p. 6):

The rainbow symbolizes the differentiation,of the Vibratory activity of light into color, by means of water suspended in the upper air. . . . The colors of the rainbow are the colors of the planetary centers.Each of the planetary centers is part of the "cosmic mind-stuff" of the angel. Correspondingly, the emblem on the angel's front is the seven-pointed star of an adept (symbolizing mastery because it requires considerable skill to make it in the traditional way, with straight edge and compass).

By controlling the drive of the libido we may go beyond the position of Hermanubis in Key 10, and rise to the point of conscious union with the Higher Self.Case applies the Kabbalah to the rest of the background. The crown is that of the Primal Will, the mountains the sefirot of Understanding and Wisdom (these form the "supernal triangle" on the "Tree of Life"). At the same time he is very much in the mainstream of classical Neoplatonism in asserting the primacy of cosmic and supercosmic forces. This is in contrast to Wirth's conceptions of universality as that of the human species and of the focusing of feelings of compassion for suffering humanity toward healing.

5. Jungian Interpretations

Sallie Nichols in Jung and Tarot (Weister 1980) analyzes the card, of which she considers the then-standard version of the Tarot of Marseille done by Paul Marteau in 1930 as somehow the original version, as the joining together of opposites. She says (pp. 249-250):

Whether we think of the red and blue opposites she intermingles as symbolizing spirit and flesh, masculine and feminine, yang and yin, conscious and unconscious, or whether their interaction is thought of as "the marriage of Christ and Sophia" or "the union of fire and water," it makes little difference, for all of these are implied. The liquid which flows between them is neither red nor blue but is pure white, suggesting that it represents a pure essence, perhaps energy.Actually the jugs are not blue and red except in Marteau's particular version of 1930; they are usually both the same color, usually somewhere between yellow and brown, or else gold and silver (Wirth). Nor is the liquid usually white; sometimes it is light blue, and sometimes merely lines against whatever background there is. Marteau's intention, as he states explicitly, is that they represent the spiritual and the material. He says (Le Tarot de Marseille, 1984 reprint of 1949 ed., p. 62):

La robe est mi-rouge, mi-bleue, car l’équilibre doit se maintenir aussi bien dans la spiritualité que dans la matière, qui ne peuvent se séparer. L’ange se penche pour bien montrer que c’est le vase bleu de la spiritualité physique qu’il déverse dans le vase rouge de la matière. Son geste et sa pose sont immuables; s’il demeurait droit, il laisserait supposer qu’il peut s’incliner de l’autre côté.

Les deux vases symbolisent le renouvellement perpétuel qui établit l’équilibre entre la matérialité et la spiritualité ; celle-ci éternellement se déversant dans l’autre vase sans jamais le remplir, la matière se renouvelant toujours. L’eau incolore, c’est-à-dire neutre, représente le fluide unissant les deux pôles et, de ce fait, se neutralisant; partant du même vase bleu et en revenant, suivant le principe du flux et du reflux des forces. .

(The robe is half red, half blue, because equilibrium must be maintained as much in spirituality as in matter, which can not be separated. The angel inclines to show that it is the blue vase of physical spirituality that he pours into the red vase of matter. His gesture and pose are immutable; if he remained upright, it would suggest that he could learn to the other side.

The two vases symbolize the perpetual renewal that establishes the balance between materiality and spirituality; this one [the angel] eternally pouring into the other vase without ever filling it, matter always renewing itself. The colorless, i.e. neutral, water represents the fluid uniting the two poles and, thus, neutralizing itself; leaving the same blue vase and returning, following the principle of the ebb and flow of forces.) .

Here [in Temperance] energy formerly experienced as two separate beasts, now revealed to be one vital In the Chariot the task of the libido was to move the hero forward on his journey. In Temperance the libido itself undergoes transformation."Libido" is a word from Freudian psychology that Jung himself also adopted, not as sexual energy but as psychic energy generally. It is an energy that somehow gets its strength, or at least part of its strength, from spirit conceived not as rationality but as the numinosity of religious experience (p. 253)

It was Jung's conclusion that neuroses represent a lost capacity for the wholeness and holiness of religious experience. In Temperance, contact with the numinous is re-established. Her two urns, like the Holy Grail and the communion chalice, have magic powers to gather together, contain, preserve, and heal.

It is Temperance who first introduces this kind of fluid discourse between the heavenly and the earthly realms, or speaking psychologically, between the self and the ego - a dialogue which will be the central theme of all the cards to follow.

...the Trinity in medieval philosophy was spirit, soul, and body. The body of course refers to Yin, and the spirit to Yang, and the psyche would be in between.

...inasmuch as the spirit is shining and hot like the sun, it is positive, but inasmuch as it is cold, it is negative. And inasmuch as a man is filled with the warmth of the spirit he will give, and inasmuch as he is filled with the coldness of the spirit, he will take, but not in a human way. It will be less than human. So to realize the spirit you must be able to think the one thing and the other: namely, that your thought is hot and cold and that you are hot and cold, that you are on the one side of god, on the other side an animal of prey. Now if the spirit cannot think that of itself—or rather, the one filled with that spirit, because the spirit is a phenomenon that doesn't think—then he has not realized the spirit. That is the pride and humility of the spirit. Usually inflated people never hesitate to realize the deity in their inflation, but they fail to realize the other side, that they are lowdown animals of prey where every value is just the reverse....:

Nietzsche: "...Many suns circle in desert space: to all that is dark do they speak with their light—but to me they are silent. / Oh, this is the hostility of light to the shining one: unpityingly doth it pursue its course. / Unfair to the shining one in its innermost heart, cold to the suns:—thus traveleth every sun."Jung: Here he identifies with the sun, the hottest thing we know of; he is entirely identical with Yang.Nietzsche: "Like a storm do the suns pursue their courses: that is their traveling."Jung: As if driven by the wind, he thought, but they themselves are the source of their movement; the sun is not driven by a storm. It is the storm, it is the movement.

Nietzsche: "Their inexorable will do they follow: that is their coldness."

Jung: Here we see the fact that the sun or the suns, the fixed stars, etc., are following a mechanical principle which is utterly inhuman; therefore they are cold, despite all heat. And that is the image or the allegory of the hunger of the spirit.Nietzsche: "Oh, ye only is it, ye dark, nightly ones, that extract warmth from the shining ones! Oh, ye only drink milk and refreshment from the light's udders! / Ah, there is ice around me; my hand burneth with the iciness!"

Jung: Now he is transforming into the cold aspect of the spirit which is the other side of its inhumanity....

There are two aspects of this "descent into the Yin": one is the dancing maidens, and the other is the well, in the depths Of the first Jung says (pp. 1171, 1172):Jung: Zarathustra and Nietzsche being practically identical are chiefly Yang, the positive masculine principle, and we can be absolutely certain that after a relatively short time the Yang will seek the Yin, because the two opposites must operate together and the one presupposes the other. He is bound to arrive at the situation where Yang reaches its climax, and then the desire for the Yin will become obvious. In "The Night-Song" we have seen how he is thirsting and longing for the Yin principle, which is nocturnal and everything feminine, just the contrary of the fiery, hot, and shining Yang. So it is quite natural that we arrive now at "The Dance-Song":Nietzsche: "One evening went Zarathustra and his disciples through the forest; and when he sought for a well, lo, he lighted upon a green meadow peacefully surrounded with trees and bushes, where maidens were dancing together."Jung: You see the fire, the Yang, seeks its own opposite, the well that quenches the thirst. And there he finds a gathering of maidens....

You remember that the general problem we have been concerned with in these last chapters is the enantiodromia, or the transition from a Yang point of View to the Yin, the female aspect. And he gives here a very good description of the anima under the aspect that she really represents: namely, chaotic life, a moving, shifting kind of life, not obeying any particular rules. At least they are not very visible, but are more like occult laws....Nietzsche, inasmuch as he is a mind, is always apt to lose himself in the icy heights of the spirit, or in the desert of the spirit, where there is light, yet where everything else is dry or cold. If he gets too lonely in that world, he is necessarily forced to descend, and then he comes to life, but in the form of the woman, so he naturally arrives at the anima. It is always a sort of descent into those lower regions where there is warmth and emotion and also the darkness of chaotic life.

But when the dance was over and the maidens had departed, he became sad. / "The sun hath long set," said he at last, "the meadow is damp, and from the forest cometh coolness.". Jung comments (p. 1174):

Naturally, when the darkness comes, when that lovely aspect of the many colors and the abundance of life has departed, then the sun sets. Consciousness goes further down into the night of the Yin, into the darkness of matter—into the prison of the body as the Gnostics would say. That the meadow is damp means that the psyche becomes humid. It was the idea of Heraclitus that the soul becomes water. It is a sort of condensation. The air gets cool in the evening and vapor becoming condensed, falls down to the ground. Out of the forest, or the darkness, comes the coolness, the darkness being of course the Yin, humidity, the north side of the mountain. And one becomes that substance, a semi-liquid matter. The body is a sort of system that contains liquids, consisting of about 98 percent water. So instantly one is caught in the body, exactly as the god, when he looked down into the mirror of matter, was caught by the love of matter, and so was locked into matter forever.

14. Having all authority over the cosmos of mortals and unreasoning animals, the man broke t hrough the vault and stooped to look through the cosmic framework, thus displaying to lower nature the fair form of god. Nature smiled for love when she saw him whose fairness brings no surfeit (and) who holds in himself all the energy of the governors and the form of god, for in the water she saw the shape of the man's fairest form and upon the earth its shadow. When the man saw in the water the form like himself as it was in nature, he loved it and wished to inhabit it; wish and action came in the same moment, and he inhabited the unreasoning form. Nature took hold of her beloved, hugged him all about and embraced him, for they were lovers.

15. Because of this, unlike any other living thing on earth, mankind is twofold - in the body mortal but immortal in the essential man. Even though he is immortal and has authority over all things, mankind is affected by mortality because he is subject to fate; thus, although man is above the cosmic framework, he became a slave within it. ... (Brian Copenhaver, ed. and trans., Hermetica, online at archive.org, p. 3)

In terms of the classical four elements, it would seem that the Yin is water and earth, and the Yang is at least fire, and probably also air, although Jung doesn't say so. For when the sun comes back out, the water of condensation vaporizes into the air. People who assign the four functions to the four elements say that fire is intuition, air is thinking, water is feeling, and earth is sensation. In that case Yang combines intuition with thinking, and Yin is more feeling plus earth. It might also be said that Yang is the dry humors (choler and melancholia) and Yin the wet ones (sanguine and phlegmatic).

If water = blue and is lower than fire = red, the assignation of colors to jugs would be the opposite of Marteau's. Given that in the Eucharist wine (red) was associated with immortality, and water (blue) with mortality, it might be thought that Jung is more in line with tradition..But it does not matter. In most cases the two jugs are the same color, and for both Jung and Marteau, it is spirit on top, matter below, which is indeed the normal way of seeing the two. Most importantly, however, Jung does not see the liquid as a blend of the two, but as something else, which he calls soul, psyche in Greek. If so, what we are seeing is soul between spirit and matter.

From Jung's discussion we can see what, for Temperance, the two extremes are that Aristotle taught that the virtues were means between, namely, spirit and matter. Leaning too far toward matter results in excess devotion food, drink, and sex. Leaning the other way leads to inflation, grandiosity, and goals or ideas cold and unfeeling as well as detached from the reality of life. Besides inflation, there can be a harshness toward oneself and others. This second extreme Aristotle largely missed. But it is not merely a matter of rationally avoiding excesses, because so much on both sides is unconscious.In fact while spirit and body may be opposites, and conscious and unconscious are also opposites, they are not the same opposites. Each partakes of both sides of the other.

Nichols does not speak about inflation, but she does identify one other way in which the two poles, conceived as the conscious and the unconscious, can each overshadow the other (pp. 254-255):

When the unconscious steps into our outer world to borrow as its dream symbols the events, persons, and objects of our daily experience; it threatens the accustomed order of our everyday life. In a similarly confusing way, the rational ego mind can intrude into the image world of the unconscious, disturbing and disrupting its healing work.It looks as though Nichols is saying that the unconscious knows what is doing. But it does and it doesn't; the accustomed order of daily life is important to hold onto; without it, life would be thrown into chaos. And it is not necessarily bad for the rational ego-mind to intrude into the image world: it depends on how it is done. In Jung's process of active imagination the two work together, each developing the other. (For some good examples see his Red Book, a record of his own experiences that was not published until 2009.)

At this point it is perhaps relevant to bring in the imagery of alchemy. Nichols speaks of alchemy as project of reducing all things to one substance, and then purifying it (p. 255)

The theory of alchemy was that all matter could be reduced to one substance out of which, by devious processes, the base and corruptible could be distilled away, so that ultimately only the pure and incorruptible, the philosophers' gold, could be bodied forth. Perhaps something similar is beginning to take place in the deepest waters of the hero's psyche. It is as if Death's harvest of partial aspects, of outworn concepts and modes of behavior (symbolized by the assorted heads, feet, and hands of card thirteen) have been reduced to one substance, out of which a new psychic being can begin to form.In that sense, the liquid passing between the two vessels is the beginning of that process, sometimes called "integration". Where Death seems to have separated, Temperance unites (p. 258).

In alchemical language, the "gluten of the eagle" and the"blood of the lion" were mingled in the "philosophical egg," or alembic, then subjected to heat. In Temperance we see pictured the beginning phase of this Great Work, the Angel's compassionate concern furnishing the heat necessary to start the "cooking" process.She does not say what this "gluten of the eagle" and "blood of the lion" are; but one appears to be white, the other red, thus feminine "philosophical mercury" and masculine "philosophical sulphur". They also might be the lion and eagle of Case's card. There is a group of pictorial examples corresponding to this process is in the 1677 Mutus Liber. The first (on page 10 of the pictures) is below.

Stanislas Klossowski de Rola, commenting on the above scene in his book The Golden Game (1997, p. 283), identifies the two substances as sulphur and mercury, being poured into a flask. The one on the right is called "flower of sulphur", according to Rola. Initially they are kept separate and weighed, corresponding to the situation of the Justice card. What happens next, on the right side of the left picture above, seems to fit what Nichols says about the Temperance card in relation to Justice (p. 254):

The opposites, which were pictured at the beginning of the Realm of Equilibrium [i.e. trumps 8-14] as the two pans of Justice's scales held apart by a fixed bar, are now shown as red and blue containers for the one unique fluid of Being.Thus in the right hand part of the left image, the two substances, having been weighed, are poured into the flask, to which in the next picture more liquid is added

In the bottom picture on the page, the sealed "egg" is subjected to a slow flame. The vessel now is this "egg", de Rola says, with a saline shell. I would guess that the set of concentric circles is to show the composition of the lemon-shaped object inside the furnace The figures of Diana and Apollo seem to be to identify the players: sol and luna, sulphur and mercury.

Three pages further, page 13, there is a similar sequence of pictures. This time there is a sun-face instead of a flower. De Rola says that the two members of the pair are now in a high state of fixity, suitable for the "multiplicatio", in which the Stone augments its power 10 times each operation..

However it is not quite as simple as Nichols initially described. For one thing, the fluid does not simply go down, following the law of gravity, but works in a circular motion, the other part being vapor. Nichols says (p. 258):

The action of the Angel Temperance as she works with the waters of the hero's psyche is like that of the sun, Nature's alchemist, on our earthly waters. The sun makes of our planet an alchemical retort in which the ocean waters are lifted to heaven and then, their impurities distilled away, are returned to earth in drops of rain. This continuous circular process epitomizes the natural interrelationship between heaven and earth - between the archetypal figures of the collective unconscious and man's ego reality.The work of Temperance, like that of the sun on the ocean and in the clouds, is then to "cleanse our faulty perceptions, connecting us in a divine yet human way with the immutable world beyond the reach of time's scythe" (p. 257). This part also much like the process of "energy" or "life-force" described by Wirth and Case.

Something like this circular process is pictured in Michael Maier's 1617 Symbola aureae mensae duodecm nationem (Symbols of the golden table of twelve nations), with Maria Prophetess as the alchemist representing the Hebrew nation; she points at two semi-circular streams of vapor between a pair of retorts; the mountain is the prima materia and the five flowers the goal of the work, the quintessence (De Rola p. 114).

Something like this circular process is pictured in Michael Maier's 1617 Symbola aureae mensae duodecm nationem (Symbols of the golden table of twelve nations), with Maria Prophetess as the alchemist representing the Hebrew nation; she points at two semi-circular streams of vapor between a pair of retorts; the mountain is the prima materia and the five flowers the goal of the work, the quintessence (De Rola p. 114).However the impurities are not all removed in one cycle. There are repeated cycles, as the pictures from the Mutus Liber illustrate, with differences among them. Also, some parts of the process are not pictured. That is true even in the analogous process of nature: besides the process from ocean to raindrops, there is also the process from raindrops to ocean, where water, through earth, acquires nutrients from the mountains and spreads them on the plain, as in the case of the Nile Flood. With the nutrients also come pollutants and disease (in the Nile flood carried by mosquitoes breeding in the receding flood) requiring more purification until it finally reaches the ocean and its poisons. Good and bad are mingled together, one impurity taking the place of another, even as the land is revived. It is similar with the conscious and the unconscious: active imagination takes the form of dialogue between the "I", the ego, and the revitalizing contents of the unconscious, revealed through dreams, visions, and reveries and continuing to act autonomously in the interaction with consciousness, continually removing our unconscious projections once they have been tested against reality Both consciousness and unconsciousness need purification. Maier's picture, when applied to the psychological process, might be reconfigured as two streams, each going in its own circle and with much mutual interaction. A final complication is that neither consciousness nor unconsciousness is purely personal. They exist in a specific milieu of family, work, region, ethnicity, nation, species, world, and cosmos. It is not an easy task to both educate the unconscious and be educated by it.