Introductory note, 2018: A version of this post,

but without images, appeared in the journal Numen Naturae, ed.

Casandra Johns, late 2018 (http://www.houseofhands.net). This essay was revised slightly in November,

2022; some parts were rearranged in January 2022. As a result, the footnote numbers are not consecutive; however, the notes themselves still work.

1. Introduction

The Tarot card now often known as the High Priestess has gone through many

changes over the years, even its name and its place in the sequence. In the first known list of Tarot

subjects, by an anonymous late 15th-century preacher in the Ferrara

region of Italy, she was “La Papessa,” the most common name by which she would

be known for the next 300 years, and number 4 from the bottom, above both her secular counterpart and her husband the Emperor. The preacher declared:[1]

4. La papessa - (O miseri quod negat Christiana fides & . . .)

4. The popess – (O wretches, which the Christian Faith denies . . . [or, “O miserable ones, because she refuses the Christian faith. . .,” or “O wretches, because the Christian faith refuses . . .”]

The line is not entirely clear, in part because it ends with

the sign for “etc.,” followed by a few more letters that no one has seen fit to

decipher. Also, the word “quod” can mean “because” as well as “which.” The

preacher is most likely saying that the Christian faith denies the validity of

such a title. But he might be saying that the Christian faith refuses salvation

to a woman who pretends to such a title, and all who honor her. Or, quite

differently (but less likely), that the card represents the Christian Faith,

which refuses something, such as card-playing, which makes people

wretched.

Although it is not known precisely what the original card looked

like, most of those that have come down to us show her in a two- or three-tiered

papal tiara, dressed in clerical garb, usually with a book, sometimes with a

staff.

So what would have come to someone's mind, seeing such a card, knowing

it was called "The Popess"?

2. “Pope Joan” and Pope-elect Manfreda

Let us start on the most literal level. There were at least two female

personages to whom the epithet of “Pope” in the feminine gender was in

fact applied, one fictional and known to many, the other real and known only to

a very few.

The well-known but fictional popess was “Pope" Joan, called “Papissa” in

Latin.[2]

In the medieval legend, believed as fact by many, she had first presented

herself as a man in order to be able to attend school and university. Still

disguised as a man, she won fame as a wise and erudite lecturer. As the

Florentine poet Boccaccio told the tale, God tolerated her success at first.

But then she accepted an offer to become Pope and won renown in that position. There is one sentence in particular in Boccaccio’s account that the

preacher seems to echo:[3]

Que tamen non verita ascendere Piscatoris cathedram et sacra ministeria

omnia, nulli mulierum a christiana religione concessum, tractare agere

at aliss exhibere.

(This woman was not afraid to mount the Fisherman's throne, to

perform all the sacred offices, and to administer them to others, something

that the Christian religion does not permit any woman to do.)

The part in bold seems close to the preacher’s

language. So, to continue the story, in God’s eyes she had gone too far.

God inflamed her with passion for a lover by whom she became pregnant. She gave

birth during a procession, thereby revealing her true gender. Naturally, she

and the child were killed on the spot by the outraged faithful.

That the card was associated with this legendary personage is suggested also in

Pietro Aretino’s satirical dialog Le Carte Parlante (The talking

cards), 1643. The cards explain to the card maker, in a series of witty

characterizations of each of them:[4]

La papessa è per l’astuzia di quegli che defraudano il nostro essere con le falsità che ci falsificano.

(The Popess is for the shrewdness of those who defraud our being with falsehoods that falsify us.)

A lady pope was for the Church a false Pope, thus one whose

actions, through their false sanctification, demeaned the very rituals designed

to secure our immortal souls. The card soon lost its high position. In the Rosenwald, c. 1500, she is just above the Bagatella. In another from around the same time, of Ferrara or Venice, she is still above the Empress, but as a female remains below the two males.

“Pope Joan” had various depictions similar to what is on the card. One is a 1488 Venice “Triumph of Love” illumination (detail at left above), as a woman dressed in papal vestments and with a papal crown, following Cupid's chariot among many others captured by his arrow.[5] Others are in 15th-century manuscripts of Boccaccio's book (below, from an Italian one of 1497 and a French one of c. 1500[6]). Her appearance is in accord with depictions of the Popess in woodblock Tarot decks of that time (above, from the Rosenwald, probably based on a Florentine design, and one from Ferrara or Venice).

The other example of a female pope giving offense to the

true religion was a real woman, Manfreda or Maifreda Visconti, wife of the first

cousin to Matteo Visconti, Lord of Milan. Then in the 14th century (1322-1373),

the Visconti rulers of Milan were accused in various papal bulls of being

followers of the cult to which she belonged, mentioning her by name and

summoning them to Rome for trial, a summons always ignored.[7]

It was mainly just harassment, but of a sort that could become serious.

What was Manfreda’s great crime? In the 17th century, an abridged version of

the trial minutes was found in a grocery shop in the town of Pavia, the second

capital of the Visconti and their Sforza successors.[8]

Pavia was also the seat of the Visconti Library, where such a document likely

would have been kept, at least until the French conquered Milan in 1500 and

shipped the whole library to Paris. In these minutes there is testimony—whether

true or false we don’t know, since torture was permitted—that she had told the

group around her that in dreams or visions a saintly laywoman named Guglielma,

then deceased, had confirmed Manfreda’s belief that she was the Holy Spirit,

conveying the news that the new “Age of the Holy Spirit” was at hand and that

Manfreda herself would head up a new Church hierarchy led by women. Such an Age

had been prophesied a century earlier by Joachim de Fiore, to replace the “Age

of the Father” and the “Age of the Son,” but it was Manfreda who identified the

Holy Spirit as not only feminine but incarnate in a simple laywoman, and the

age to come as one with women at the helm. With her small sect (which included

men), Manfreda conducted masses and waited for Guglielma’s imminent return from

the dead, just as Christ had risen to herald the “Age of the Son.” When the

event did not come about by Pentecost of the year 1300, someone seems to have

betrayed the cult to the Inquisition.

The relevance to the Tarot is that the earliest known Popess

card appears in a hand-painted Tarot deck probably done for Duke Francesco

Sforza of Milan and his wife Bianca Maria Visconti, a direct descendant of the

Matteo Visconti lord whose first cousin was Manfreda (far right). In that deck,

still extant, the Popess wears the characteristic three-tiered papal crown; but

instead of papal vestments, she has a simple nun’s habit of brown robe with

white wimple.[9]

According to the trial document, the members of the group wore dark brown

robes. The color on the card is not that dark, but the color on a similar card,

now in a museum in Spain, is indeed dark brown (near right). The woman on the

card also has a belt with three knots. The secret cult to which Manfreda

belonged associated such knots to a “miracle” described in the trial minutes.[10]

There is no direct evidence that Bianca Maria Visconti, a probable

sponsor of the deck, knew about Manfreda, although the bulls against the

Visconti naming her had been public documents. They did not mention that

Manfreda had claimed the office of Pope, but given the papacy’s recurrent

accusations against the Visconti, it seems plausible that details of Manfreda’s

heresy would have been passed down to her, as the only child of the late

Visconti duke, including what was in the document that later surfaced in Pavia.

Manfreda’s presence in a deck of cards would have provided an instructional

reminder from parents to children for descendants of this unusual relative.

There seem to be other cards in the deck that reflect members of the Visconti

family (Love, Chariot, Hanged Man, and probably others, for which see my posts

on those cards). It is possible that Bianca Maria even admired cousin Manfreda.

If so, it is a rather positive endorsement, because both the cross-staff and

the book she holds were traditional attributes of Wisdom or Prudence - in

particular, given the cross, the wisdom of Christianity.[11]

It is entirely possible that there is in fact no direct

corres pondence between the Tarot sequence and any specific overarching spiritual

conception that came before it. In the earliest extant Tarot deck, now owned

by Yale University and probably done in the 1440s for a member of the Visconti

or Sforza family, neither Pope nor Popess is among the surviving cards, but an

Emperor and Empress are[23], and a different image represents Faith, that of a woman holding a cross-staff

and a goblet (far left), an image also seen in the c. 1470 card labeled Fides in

the so-called “Tarot of Mantegna” (near left).[24]

Then the Pope card might have been added after the game was already

invented, so as to signify the Pope’s supremacy over the Emperor.[25]

Then the Popess could be added as a whimsical parallel to the

Empress. In that case, any further meaning to the sequence might have been left

to the viewer. If so, there were numerous associations to choose from, not only the irreverent ones just considered but orthodox ones, too.

pondence between the Tarot sequence and any specific overarching spiritual

conception that came before it. In the earliest extant Tarot deck, now owned

by Yale University and probably done in the 1440s for a member of the Visconti

or Sforza family, neither Pope nor Popess is among the surviving cards, but an

Emperor and Empress are[23], and a different image represents Faith, that of a woman holding a cross-staff

and a goblet (far left), an image also seen in the c. 1470 card labeled Fides in

the so-called “Tarot of Mantegna” (near left).[24]

Then the Pope card might have been added after the game was already

invented, so as to signify the Pope’s supremacy over the Emperor.[25]

Then the Popess could be added as a whimsical parallel to the

Empress. In that case, any further meaning to the sequence might have been left

to the viewer. If so, there were numerous associations to choose from, not only the irreverent ones just considered but orthodox ones, too.

3. Early orthodox associations to the Popess card

Any identification of the Visconti-Sforza Popess with a Visconti pretender

would presumably, by the 1450s when the card was done, have been unknown

outside the circle of Visconti descendants and perhaps a few Church officials.

For others, non-heretical associations to the card would have been ready to

hand, of an allegorical nature.

As we have seen, on one reading of the Sermo, albeit the least likely

one, "the Christian Faith" might be the subject, refusing to the

people called "wretches" something left unsaid. On that reading, the

Popess could represent the Christian Faith, or something similar.

More persuasive for this interpretation are her clothing,

tiara, and place in the sequence. Dressed like the Pope, she could signify the

Pope's wife, which for St. Thomas Aquinas and canon law was the Church,

declared to be the legal spouse of the Pope. That reading is also suggested by

her place in the Sermo's order, immediately below the Pope, just as the

Empress is immediately below the Emperor.[12]

On the other hand, in some early lists, and almost universally after the 16th

century, the Popess was second in the order. Given that the Empress and Emperor

were still put next to each other, in that order she is less likely to have

been thought of as the Pope's wife. But she could still be the Church as an

institution separate from the papacy. At that time in many places, the secular

rulers controlled the local ecclesiastical appointments. If it was desired to

endorse that arrangement, putting her below the two imperial cards would have

been especially appropriate.

She could also represent the Church if she is dressed as a simple nun, as in

the Visconti-Sforza card. Franciscan “tertiaries,” as the order’s lay nuns were

called, wore just such brown robes with white wimples, as well as cords with three

knots.[13]

Moreover, women with book and cross-staff were sometimes associated with the

virtue of Faith in manuscript illuminations. [14]

In that tradition, Giotto, in c.1305-1307 Padua, famously depicted Faith with

cross-staff and scroll as well as a conical hat with a cross on top, not

dissimilar to that worn by popes then (below middle, with "Fides" at

the top). The scroll has on it the first words of the Nicean and Constantine

creeds.[15]

Another image in the same vein is from England of the second half of the 15th century: a lady in a three-tiered crown helps a Wheel of Fortune turn upward, in an illumination to Lydgate’s Siege of Troy (detail with crowned ladies above right); she is probably the “dame doctryne” of another work, Assembly of the gods, by an unknown author, described there as “crowned with three crowns.”[16]

Among the theologians read at the time of the early tarot, several saw the way to God as a ladder to heaven, whose steps they then described. It is possible that the early tarot was seen in that way, perhaps even constructed with that idea in mind, since the cards are arranged hierarchically; this last would have been a necessity in any trick-taking card game played with them. The Popess could have a place in such a schema.

St. Augustine (354-430) described a seven-step path to Wisdom, of which the first is “fear of the Lord”. Then for the second step:[17]

Then we must become gentle by piety. We ought not protest against Holy Scripture, either when we understand it and it is attacking some of our faults, or, when we do not understand it, and think that we ourselves could be wiser and give better advice. In this latter case we must rather reflect and believe that what is written there is more beneficial and reasonable, even if hidden, than what we could know of ourselves.

Holding the book in her hand, the Popess presents herself from this perspective as the personification of this step, Piety, a close cousin to Faith. Notice in the above that there is already the idea of concealed truth, as something hidden beneath the surface of the words. The book alone is not enough; there is also the meaning (or meanings) behind the words, for which there was the Church to guide and deepen the understanding.

St. Bonaventura (1221-1274) spoke of six stages in the ascent to God, starting with “sense”, then “imagination,” and so on until “illumination.” Turning to the world experienced by the senses, he spoke of a series of “modes” of apprehension.[18] The first mode is that of looking at it in terms of magnitude, i.e. weight, number, and measure, from which, by contemplation, “one can rise as from the traces to understanding the power, wisdom, and immense goodness of the Creator.”

The “second mode is, as for Augustine, that of the person of faith:

In the second mode, the aspect of a believer considering this world, one reaches its origin, course, and terminus. For by faith we believe that the ages are fashioned by the Word of Life [Hebr. 11, 3]; by faith we believe that the ages of the three laws--that is, the ages of the law of Nature, of Scripture, and of Grace--succeed each other and occur in most orderly fashion; by faith we believe that the world will be ended at the last judgment--taking heed of the power in the first, of the providence in the second, of the justice of the most high principle in the third.

Here “faith” has much the same role as “piety” in Augustine, that by which one comes to know the teachings of the Church.

There were various ways of describing the ascent. In an illustration to The

Holy Mountain of God (1477, above right), for example, a monk climbs a ladder whose

rungs each have a label: Humility at the bottom, followed by Prudence

and the other cardinal virtues, then other virtues. There were numerous such

ladders,  as early as the twelfth century.[19]

as early as the twelfth century.[19]

Faith is a logical meaning for a Popess to have, seen as a lower rung on a ladder

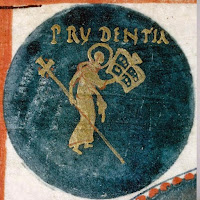

leading to God. But Prudence and Wisdom also

fit. Both, even more often than Faith, were shown in illuminated manuscripts as

women with a book and cross-staff, as on the Visconti-Sforza card. For Prudence (e.g., the image above right[20], her book, besides being that of supreme wisdom (the Bible), gives the lady

holding it the allegorical value associated with that virtue, Prudence, which St. Thomas

Aquinas said “moved” all the others.[21] It is God’s gift of rationality, to recognize the right

means to the right end.

Alternatively, if “the fear of God is the beginning of Wisdom,” it would be fitting that Wisdom be present early in the sequence, as the inspiration of the book she holds and the object of reading it. Also, as the personified “Wisdom of God” in the Hebrew Bible, she was “with God from the beginning,” perfecting his work of creation, thus appropriate for the second spot, to the extent that the Magician represents the initiator of creation. (Or the Magician, as a trickster, might represent the sinner, on the bottom rung for that reason.) A Northern Italian illumination of Wisdom comparable to the Popess is a 13th-century illumination in Florence of a crowned woman (not a papal crown) sitting with cross-staff and book, illuminating the first letter of an Old Testament verse in which Wisdom is treated as a feminine personification (at left above).[22]

There was also the Crowned Virgin, in numerous guises. As The Lord’s Mercy in 1348 (below, far left), her crown was not divided into tiers, but that crown seems not to have been used by the papacy until 1315, and artists sometimes continued to use a simple conical one after that;[26] an example is the Pope card of the 1450s-1470s “Charles VI” Tarot, probably from Florence (second left).[27]

A papal-style crown was also given to the Virgin in her role as Queen of Heaven. In 1400 Siena, for example, she is being crowned with a two-tiered crown (far right),[28] while in 1446 Cambridge, England (near right),[29] she was shown with a three-tiered crown like that of the Visconti-Sforza Popess.

That the Tarot lady held a book also associated her with the Virgin Mary,

traditionally depicted at the Annunciation pointing to the passage in Isaiah predicting the birth of the Messiah (at right).[30] A card particularly suggestive of this association is a c. 1709 Lyon version by Jean Dodal (near right). He entitled the card

“Pances,” a term meaning “paunch” or “belly,” also a term for the womb.[39] If the figure looks older than the teenage Virgin, it may be that we are seeing her when she is older and presumably wiser: it is still the same womb, with its precious cargo.

That the Tarot lady held a book also associated her with the Virgin Mary,

traditionally depicted at the Annunciation pointing to the passage in Isaiah predicting the birth of the Messiah (at right).[30] A card particularly suggestive of this association is a c. 1709 Lyon version by Jean Dodal (near right). He entitled the card

“Pances,” a term meaning “paunch” or “belly,” also a term for the womb.[39] If the figure looks older than the teenage Virgin, it may be that we are seeing her when she is older and presumably wiser: it is still the same womb, with its precious cargo.  Alternatively, it might be a jab at “Pope Joan,” who in the story gave away her feminine identity by giving birth on a procession.

Alternatively, it might be a jab at “Pope Joan,” who in the story gave away her feminine identity by giving birth on a procession.

Interpreted as protagonist of the Annunciation, the next card in the sequence will also fit the Virgin. The Empress typically holds on her lap a shield with the image of an eagle. The position is reminiscent of the numerous Madonna and Child paintings that were visible everywhere (at right Dodal's Empress and Cima da Conegliano's Madonna and Child in a Landscape, c. 1496–99, Los Angeles County Museum of Art). The eagle was a symbol of God's protection and feirceness in the Hebrew Bible and of Christ in Christianity. As the insignia of

the Holy Roman Empire, the association to a child also showed the Empress's vital role as the bearer of future rulers and therefore the future of the empire.[40]

While Dodal is already 18th century, with a woman too old to be the Virgin of the Annunciation, some early Popess cards did show a rather young woman. Moreover, the Bembo workshop of Cremona, which was responsible for the earliest known card, did make

some of its depictions of the Virgin—at the ascension of Jesus and at her

coronation in heaven - strikingly like the mature woman they painted for this

card. Below are my examples, both judged to be from the early 1440s. On the upper left is a

"Coronation of the Virgin" and on the upper right an "Ascension

of Christ."[32]

Below them, I have put close-ups of the Virgin's face compared with that of the

Visconti-Sforza card.

The Bembo workshop's Coronations of the Virgin suggest not only the Virgin but also the Wisdom of the Old Testament. All three of those known show the Father crowning both Christ and the Virgin, whereas most show Christ crowning the Virgin. Moreover, the usual dove, representing the Holy Spirit, is absent. Since Christ as the Logos pre-existed the creation, the inference is that the Virgin did so as well. The difference may have to with the Virgin's immaculacy (this idea is developed by Edith Kirsch, "Bonifacio Bembo's Saint Agostino Altarpiece," in Studia di Storia del' Arte in onore di Mina Gregori, 1995, pp. 48-49 and by Marco Tanzi in Arcigoticissimo Bembo: Bonifacio in Sant'Augustino e in Duomo a Cremona, 2011, pp. 26-28.). If she is immaculate - without stain -, as St. Augustine had maintained, then she is not a descendant of Eve. The only such feminine being is Sophia. The absence of the dove suggests that she is also the Holy Spirit. If so, then these coronations also relate to the filoque ("from the son") controversy at the Council of Flornece in 1438-1439, in which the Roman Church held that the Holy Spirit descended from both the Father and the Son, whereas the Greeks held that it descended only from the Father. If the former, then the Son could crown the Holy Spirit, but if the latter it could not. The paintings would reflect the Greek position.

4. From Popess to High Priestess

During the Renaissance a papal crown was also associated with female pagan

figures. In 1470s Florence, it appeared on the Libyan sibyl, below left, in

Baldini’s series of sibyls and prophets; three other of his sibyls, the

Delphian, Phrygian, and Tiburtine have variations on the conical crown.[34]

These sibyls were priestesses at oracles and thought by the sayings associated

with them to have elusively predicted the coming of Christ.

In 1499 Venice, in the illustrated Italian allegorical novel

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Strife of love in a Dream of Poliphilio), the

abbess—i.e. head priestess--of a nunnery of Venus was depicted with a similar

three-tiered crown, above right.[35]

In the text she is called Antistite, Latin for “high priestess,” and Ierophantia,

a Greek-derived term for the same.

In 1544 Lombardy the jurist and emblem-book writer Andrea Alciato applied the

term flaminicam (accusative case) to the card, a Latin word for

“priestess.”[36]

The term applied to the wife of a Roman priest, or flamen, in charge of

the cult of a particular god; she, too, would have important duties in the cult.[37]

Since there were assistants, if they were also priests the flamen and flaminica

(nominative case) would qualify as a high priest and high priestess. As

the wife of a high priest (in the cult of a particular god), one might think

also of the mistresses that popes historically had, during the 15th

century and before: [38]

In 1781, Antoine Court de Gébelin repeated Alciato's title, but in French, adding the adjective "Grande," meaning "High," which was probably already implicit in the title "flaminca." As in Rome, she was the wife of the priest in charge of the worship of a god, but for de Gebelin she is not Roman but Egyptian, in accord with hisidea that the Tarot originated in Egypt. He perceived two horns on the sides of the lady’s crown, which he said was thus “like that of Isis”;[41] his drawing of the card showed two long points on the right and left side of the Popess’s crown. In fact, the Popess’s crown on at least one Swiss deck of that time (Gébelin had grown up in Switzerland) shows similar points, although the corresponding ones in Marseille, and Paris of an earlier time, are shorter.[42] Unless one were specifically looking for suggestions of Egypt, these points would simply be taken as those often accompanying crowns.

De Gebelin also perceived on his Priestess “a kind of veil behind her head that crosses over her stomach” (une espèce de voile derriere la tête qui vient croiser sur l'estomac).[64] Typically a "veil" is somethng that covers part of the face. His picture shows no such covering (see above), Probably he is referring to the curtain behind her, a feature that had been added already by the middle of the 17th century, of which the first examples are in Paris of around 1650. We are justified in wondering why that addition would have been made, and why Gebelin called it a veil.

Plutarch had reported on a statue of

“Athena, whom they believe to be Isis,” an inscription that was translated as,

“I am all that hath been, and is, and shall be; and my veil no mortal has

hitherto raised.”[71]

Plutarch’s Greek word pelops, customarily translated as “veil,” actually

meant “garment” or “robe”, an error promulgated by the Florentine

humanist Marsilio Ficino in the late 15th century.[73] Except for the precise term, it makes little difference. From the late 16th century onwards, this saying, usually with explicit

reference to Isis, was interpreted by numerous authors as referring to the

secrets of nature, which was thought to be "unveiled" by science.[72]

An example is at left, Nature

being unveiled by science, the frontispiece to Gerhard Blasius's 1681 Anatome

Animalum, engraved by Jan Lyken. What had been a veil is now behind her head. That the figure has multiple breasts

indicates not only the abundance of nature but an association both with Isis

and with Diana, whose statue at Ephesus was said to have been of that type.

Plutarch had reported on a statue of

“Athena, whom they believe to be Isis,” an inscription that was translated as,

“I am all that hath been, and is, and shall be; and my veil no mortal has

hitherto raised.”[71]

Plutarch’s Greek word pelops, customarily translated as “veil,” actually

meant “garment” or “robe”, an error promulgated by the Florentine

humanist Marsilio Ficino in the late 15th century.[73] Except for the precise term, it makes little difference. From the late 16th century onwards, this saying, usually with explicit

reference to Isis, was interpreted by numerous authors as referring to the

secrets of nature, which was thought to be "unveiled" by science.[72]

An example is at left, Nature

being unveiled by science, the frontispiece to Gerhard Blasius's 1681 Anatome

Animalum, engraved by Jan Lyken. What had been a veil is now behind her head. That the figure has multiple breasts

indicates not only the abundance of nature but an association both with Isis

and with Diana, whose statue at Ephesus was said to have been of that type.

Although there is no veil over the Popess's face, the 17th century cards that add the curtain also make her face quite mask-like. Her true face, ugly or beautiful, must be hidden from the world.

Another reason for thinking that a tradition already existed associating the cards with ancient Egypt dates back to the late 16th to early 17th century. If we compare the 1557 Lyon deck of Catelin Geoffroy in 1557 Lyon with the 17th century Parisian cards of Viéville and Noblet, an interesting switch happens: diagonal straps that in 1557 go across the Pope’s chest but not the Popess’s, in the later decks are on the Popess but not the Pope.[45]

While such straps were not unknown as papal attire, their switch to the Popess would suggest, to those partaking of the “Egyptomania” in educated circles of the time, the diagonal X of two strips of cloth that went across the chest of Isis and her priestesses in statues preserved in Italy from the Roman period.[46]

In this context, the Egyptian Isis is

identical to the Greeks' Athena, goddess of wisdom, as

well as the Sophia, Greek for Wisdom, of the Old Testament, Hochmah in Hebrew. The High Priestess would

then be the bearer of that Wisdom in veiled form, both through the book she

holds and the child she, as Mary, gives birth to.

If so, the change of name from "Popess" to "Priestess" suggests not so much a paganizing of the card as a desire to get beyond the particularities of Roman Catholicism to its pagan parallels, seen as remnants of a prisca theologia, "ancient theology," that both anticipated Christianity and reflected, in debased form, the teachings of God to Adam and descendants from before the Flood. From this perspective, prior religions added a depth of symbolism that would enable the seeker to transcend the popular imagery of medieval Christianity so to get closer to its inexpressible essence. This doctrine, advocated by such thinkers as Ficino and Pico, was fashionable even in late 15th-century Italy.

In this regard the Cary Sheet of c. 1500 is of interest.[47] One of the cards (above left) might be the Pope, because of its place on the sheet next to the Emperor, and because acolytes are typically shown on that card (two of them).[48] But it might be the Popess, because the Milanese order is not followed precisely (the card on the other side of her on the sheet is Strength), and she is young and beardless (although one early Pope card, the Rosenwald, is similar). It shows a young person with a bishop’s crozier, a book, and a kneeling male acolyte (mirror image on left above). In composition its mirror image (as would have been presented to the cutter) is similar to a painting of Isis in the papal apartments of Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) of the early 1490s (on the right); both are young and beardless, seated with a book in front of them and a young man kneeling at one side.[49] The fresco in the papal apartment has another man on the other side; the theme is Isis teaching Hermes Trismegistus and Moses.[50] The connection between this fresco and the Cary Sheet is that the latter is most likely from Milan, and Cardinal Ascanio Sforza, brother of the Duke, was Alexander’s decisive supporter in the election and his Chancellor during the period when the fresco was executed.

Etteilla and Mozart.Whenever the change from Popess to Priestess occurred - probably as a gradual transition, with overlapping interpretations - de Gebelin's idea was quickly taken up by others. In Vienna of 1791, ten years after Gébelin, we see an opera

specifying in its libretto veiled ladies standing in front of a temple, which now takes the place of the curtain.Through their magic they have managed to kill or at least depotentiate a snake - in the illustration, it can still raise its head even when cut in pieces. Perhaps it corresponds to the Bagatella, who is something of a snake himself. All they are missing is the Popess's book. Their goddess is nature, not an articulate Sophia whose words can be recorded for posterity. We will meet that goddess in the next card, the Empress.

Mozart was an avid

player of tarock,[43]

- including the Tarot of Marseille version he would have encountered in Milan if not also in Vienna; several of the characters seem to embody, in a playful way, figures of its trump sequence: Papageno as

the Fool and the Hanged Man (he tries to hang himself), Sorastro as the High

Priest (who makes his entrance on a chariot), the evil Monostatos as the Devil, the Queen of the Night as a negative Empress, her daughter Pamina and the hero Tamino as the Lovers and future Emperor and Empress. It is possible

that Mozart and Gébelin were independently drawing on a preexisting tradition

about the Tarot, perhaps within the Freemasonry to which both belonged. But

news of Gébelin’s essay would have traveled to Vienna quickly enough.[44]

Etteilla, writing in the 1780s, is in much the same world as Mozart. His deck has no Popess or Pope card, or even Gébelin's equivalents, the

High Priest and Priestess. As Church and Pope, these cards are too associated with the old regime that the

Revolution was trying to remove. Instead, as befitting a professional tarot reader, he has a "Male Enquirer"

and a "Female Enquirer." The upright keywords for the female enquirer have intimations of a religious figure, but without the authority suggested by the title "Popess," or even "High Priestess." Below

I have combined two lists from Etteilla's followers; the words in bold are from "Julia

Orsini," 1838 only, and those in italics from Papus, Divinatory Tarot, only (the card shown is late 19th century, but to Etteilla's original design):[108]

Upright: Nature, repose, tranquility, retreat, secluded life, hermit's [or hermetic] life, religious life, Orphic life, solitude, peace and quiet of old age. Temple of ardour, silence, taciturnity.

Reversed: Imitation, Garden of Eden, effervescence, seething [boullionment, boiling], fermentation, ferment, leaven, acidity.

The uprights suggest the three ladies of the Magic Flute. I am reminded also of the legend about the later life of Mary Magdalene, after Christ's death, when she retreats to a cave in the mountains outside Marseille, secluded from the world. “Garden of Eden” is suggested by the scene on Etteilla's card, a woman in nature. But the wished-for tranquility of the Uprights may mask a seething interior, hidden even from oneself, given in the Reverseds. Both are apt for a woman coming to a tarot reading, the one for her exterior presentation, the other for a troubled interior.There is also what Etteilla does with the Empress card, which by the same revolutionary considerations, he replaces with a card whose keywords are "Night" and "Day." While the keywords for "Day" are appropriate for a heroine (like Mozart's Pamina), it is worth quoting here the Etteilla school's word lists for "Night," appropriate to Mozart's evil Queen: [107]

NIGHT—Obscurity, Darkness, Lack of Light, Night Scene [Fr. Nocturnal], Mystery, Secret, Mask, Hidden, Unknown, Clandestine, Occult Eclipse.—Veil, Symbol [Emblème], Figure, Image, Parable, Allegory, Mystic Fire, Veiled Purpose, Mystic Meaning, Mysterious Words, Obscure Discourse, Occult Science.—Hidden Machinations, Mysterious Intervention, Clandestine Actions, In Secret, Clandestinely, Derision.—Blindness, Confused, Entangle, Cover, Wrap, Forget, Forgotten, Difficulty, Doubt, Error, Ignorance.

Several of these characterizations would qualify as

"shadow" aspects in a Jungian sense, characteristics that one despises

in others but does not recognize in oneself, i.e. hidden machinations,

clandestine, derision, blindness, confused, forget, doubt, Ignorance. Others

are more "persona": Veil, Symbol, Figure, Image, Parable,

Allegory, Mystic Fire, Veiled Purpose, Mystic Meaning, Mysterious Words, Occult

Science. These are ready-made for the occultists to come - and, I expect, for the various secret societies with "Egyptian rites" (Freemasons and their competitors, such as Cagliostro) in France of his time.

5. The Occultists

Occultists in Paris of the second half of the 19th century jumped on the bandwagon. Eliphas Lévi

(birth name Alphonse Constant), who revived Gébelin’s suggestion, wrote in

1856, “She has all the attributes of Isis.”[51]

In 1863 Lévi’s student Paul Christian (Jean-Baptiste Pitois) called her “occult

Science waiting for the initiate on the threshold of the sanctuary of Isis.[52] For him the folds of her veil “partly

covered her face”; she thus represents “occult knowledge,” to be communicated

when the recipient is ready to receive “nature’s secrets.”[69]

In 1889 Lévi’s later follower Papus (Dr. Gérard Encausse) wrote, “She is the

picture of Isis.”[53] He again identifies her with nature

and says

the veil represents the hiddenness of nature’s secrets, thus referencing

the tradition inspired by Plutarch's comment about the "veil of Isis."[70]

Lévi defined the “horns” that Gébelin had seen on her crown

as those of a crescent moon; Christian located this crescent at the tiara’s top

rather than its sides and also associated her astrologically with the moon;

Papus adopted both innovations, and for his 1889 book Tarot des Bohemiens

his associate Oswald Wirth drew a Priestess with a crescent-tipped triple crown

(far left). When Maurice Wegener created a set of images to make the cards look Egyptian, published in 1896 with Robert Falconnier's text, he,

too, put the crescent on top. Unlike Wirth, he gave her a veil that covered

most of her face (at left, on the right). Wegener’s designs were adopted by C.

C. Zain in the United States, where they are still available today.[54]

An association between Isis and the moon was not inappropriate, as well-known

ancient writings about her as a goddess – Ovid, Diodorus, Apuleius - had

already made it, and to numerous other goddesses.[55] Since she was also associated with magic, such an association would also tend to connect her to the Roman moon-goddess Diana, who was often

mentioned in witches’ testimonies to the Inquisition in 15th-century

Italy as the supernatural power connected with their “night-riding” cult.[56]

Diana in pagan times had been imagined as living in the forest with her nymphs

hunting game and avoiding all contact with men; she was thus very much outside

any accepted female roles. At the same time, she was the guardian goddess of

childbirth.[57]

Since the country “witches” who associated themselves with Diana were probably

mainly midwives attuned to the menstrual cycle and folk herbalists harvesting by the moon, the relationship is a natural one. This work also associates them with Isis,

well known for her healing powers.[58]

Lévi, besides speaking of Isis and the "veil" behind her, also notes at each side “two pillars of the duad,” which he claims he saw on an old card.[67] So he speaks of the pillars Boaz and Jakin of Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 7:15, 7:21; 2 Kings 11:14, 23:3), saying they represent the active and the passive in various forms, with the union of the two as wisdom.[68] He does not specifically mention the Priestess, arcanum 2, but it is in his chapter 2, entitled “Chokmah,” “wisdom” in Hebrew, for the second sefira on the Kabbalists’ Tree of Life and by inference the second arcanum of the tarot.

Like Lévi, Christian specifies two columns behind her; these represent “the portal of the occult sanctuary,” also called “the threshold of the sanctuary of Isis.” Papus adds that the two columns express “the positive and the negative.”[80]

Wirth, in his own book of 1927, says that that with this second arcanum duality appears, e.g. Father/Mother, Subject/Object, Creator/Created,” as well as light and dark, good and evil, happiness and suffering: “Good would be unknown to us if it were not for evil,” he observes, and so also happiness in relation to suffering.[81] Thus in Wirth's design for the card (1927 version at left) he put black and white tiles on the floor and the Yin/Yang symbol--a circle made of two swirls, one black and one white, each with a dot of the other color in its head--on the cover of the Priestess’s book. In his divinatory interpretations he also brought out the negative side of the Popess’s fixity and secretiveness: “deceit” (duplicity), also “inertia, laziness, intolerance, bigotry, fanaticism.”[82] For Lévi and the others in this French tradition, the

Priestess corresponds to the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet, Beth, which

in Hebrew means “house” as well as serving as the number 2. “House” signifies for

Lévi “the house of God and man, the sanctuary, . . . the occult church.”[88]

Papus adds: “Beth expresses that inner self, central as a dwelling, to which

one can retire without fear of disturbance.”[89]

In 1909 London. A. E, Waite replaced the tiara by stylized

cow’s horns, also suggesting a lunar crescent and the sides of a cup, with what

appears to be a full moon between them;[83]

the result is a headdress vaguely like those of Isis and Hathor in Greco-Roman

Egypt (Waite-Smith card in the center above; outer wall of Dendera Temple, c.

50 b.c.e, at right). The white color and shapes of the two sides suggest the moon. In regard to Isis, on the one hand, she was one of several gods and goddesses reported by Plutarch as children of the Moon goddess; on the other hand, interior versions of the scene elsewhere show the circle painted red, suggesting the sun. There is also a crescent

moon at the High Priestess's feet suggestive of the “woman clothed with the

sun” of Revelation 12:1. The sun may be suggested by the circles around the pomegranites. The symbolism is still that of Isis, but

with Christian symbolism of the Virgin, both at the Annunciation (since she

looks quite young) and at the Apocalypse.

Waite kept the pillars, black and white, still labeled B and J, and spoke of a

“veil” behind her. At the same time what is pictured between the pillars

are pomegranites suggesting the sefiroth on the two sides of the Kabbalist “Tree of Life.” The

High Priestess’s own position in front of the middle of the Tree corresponds to

the Golden Dawn’s placement of her on the central column on a line connecting

Kether at the top with Tifereth in the middle, making her “the direct

connection from the highest consciousness, across the Abyss, to the middle

consciousness,” as the Llewelyn Encyclopedia’s summary says (the green line on the diagram at left).[84] The associated Hebrew letter, in the Golden Dawn tradition, is

Gimel, the third letter, for the third arcanum starting from the Fool. The

letter means “camel,” the animal “whose ability to store water enables the

traveler to cross the Great Divide,”[85]

meaning from the top three sefirot to the seven below.

According to Waite, on the Tree of Life she is both Binah (Understanding, sefira 3), the Supernal Mother who reflects the light to those below, and Malkuth (Kingdom, sefira 10), Queen of the borrowed light, nourished by the milk of the Supernal Mother. "She represents also the Second Marriage of the Prince who is no longer

of this world; she is the spiritual Bride and Mother, the daughter of

the stars and the Higher Garden of Eden." She is also "the Spiritual Bride of the

just man," for whom "when he reads the Law she gives the Divine meaning." [86] That the scroll is partly concealed indicates that the Law is only partially accessible.

What is the reference for "the Prince no longer of this world"? Looking in Waite's Holy Kabbalah, p. 369, I find only one male Kabbalistic entity who has even been in this world, and that is Da'at, born of Binah and Hochmah, along with a twin sister Grace, and both descended to earth (p. 369). But did he ever leave? Waite does not say, that I can find. A better possibility is Moses, who ceased relations with his wife when the Shekinah cleaved to him (p. 355). There is also a tradition that the Holy One married Moses to the Matrona, i.e. Binah (p. 356, citing the Zohar). Waite refers to Moses as "the prince of lawgivers" (p. 358). Another is Christ. His first marriage would have been to the Church, on the Cross, and mystically to Mary at that same occasion (see https://catholiccounselors.com/christs-spousal-gift-on-the-cross/). His second marriage would be to that same Mary as Crowned Virgin after her Assumption.

Writing in 1936, Paul Foster Case essentially adopted Waite's design, but added the Hebrew letter that the Golden Dawn associated with the card, Gimel, and changed the B and J to the corresponding Hebrew letters (at left). She corresponds to the "subconscious", meaning for him in part the material world (Tarot Fundamentals, Lesson 8, p. 1, online), which he says is essentially mind, at a lower frequency of vibration, but having a perfect memory (represented by the scroll) and following the laws of logic. It is the basis of all physical structures, but in itself is fluid, like water, hence the flowing quality of her robe. Besides this "universal subconscious", there is also a personal subconsciousness of our own history. He identifies the card especially with Hecate, goddess of the moon, goddess of the hunt and childbirth on earth, and queen of the underworld (Ibid, 7-6). Thus she governs our mental process while asleep or in reverie, but also connects distant places in space. The pillars represent "all pairs of opposites," unified by the veil. The cross represents light, and also Hecate as goddess of crossroads that meet at right angles. Since all we are usually aware of are the superficial aspects of the subconscious, its appearances rather than its essence as mental vibration. He adds (pp. 8-7):The right hand of the High Priestess is hidden, because the more powerful activities of subconsciousness elude our attempts to analyze them. Her left hand, therefore, is the only one visible, to intimate that we perceive only the end results, or relatively superficial manifestations of the occult forces she represents. Besides the right hand, there is the veil and the rolled-up scroll, both hiding more than they reveal.

T his identification of the Priestess with Hecate gets added confirmation when we look at the typical image of this goddess in ancient times. Statues of her in

trimorphic form would be erected at crossroads where three roads met and at the entrances to houses. She guarded the

boundaries between worlds and also protected those traveling from one to

another, whether from this world to the underworld or to celestial realms (see Wikipedia entry on her). In keeping with this function, she was iconographically associated with keys, and in that regard similar to some of the historic Popess cards.

his identification of the Priestess with Hecate gets added confirmation when we look at the typical image of this goddess in ancient times. Statues of her in

trimorphic form would be erected at crossroads where three roads met and at the entrances to houses. She guarded the

boundaries between worlds and also protected those traveling from one to

another, whether from this world to the underworld or to celestial realms (see Wikipedia entry on her). In keeping with this function, she was iconographically associated with keys, and in that regard similar to some of the historic Popess cards.

The imagery of her standard household statuary (at right, from the time of Hadrian) in a doorway also fits the High Priestess from Levi onwards quite well, where she stands in front of a sanctuary hidden from view. When we add her association to the moon and to the underworld (corresponding to Case's "subconscious"), Case is surely on target when he says, "Indeed, it is principally from the attributes of Hekate that the symbolism of the second Tarot Key is derived." We will see later that her mythology also enriches the cards at the other end of the sequence, especially the Moon.

7. The Jungian turn

For Jung, archetypes have both positive and negative attributes and effects. While the majority of the occultists focus on one or the other side of this divide, it is Oswald Wirth who has the clearest appreciation of both sides, because he divides the associations into "good" and "bad."[98] For "bad" he has: "deceit, hidden intentions, spite, inertia, laziness, bigotry, intolerance, fanaticism." That is, when dealing with "hidden knowledge," which the High Priestess is said to guard, anyone who disagrees with one's own intuitions is thought to possess one of these. Thinking of the Inquisition’s attitude toward Manfreda, we might add "diabolical," "leading people astray," and the like. Those persecuted would similarly apply Wirth's negative list to their persecutors.

On

the positive side, Wirth's "good" meanings are "divination,

intuitive philosophy, knowledge (gnosis) discerning mystery, contemplative

faith, silence, discretion, reserve, meditation, modesty, patience,

resignation, piety, respect for holy things." Where do these fit into

Jungian psychology? On the one hand, they might be personal traits verifiable

in an individual's behavior. They could also be part of what Jung calls the

"persona," namely, that part of the personality that a person

presents to the world, also internalized as part of one's self-image, to

oneself and others.[99]

To a certain extent, this opposition of persona and shadow is captured when tarot readers use one set of meanings when a card appears upright and the

opposite when it appears reversed. In the

case of the High Priestess, Waite has among the "reversed" meanings

that of conceit.[100]

From the standpoint of the Inquisition, Manfreda in opposing the Church was

guilty of the sin of pride. To Manfreda, of course, it was the Inquisition that

was full of pride.

Once one examines one's personal shadow, one's disowned traits, one may, with luck, find the anima. For Jung the anima is an interior figure in men that

can be destructive when unconscious but can also, when made conscious, lead a

man toward a confrontation with the Self, as the totality of his being.[101]

In this regard Sallie Nichols writes:[102]

When a man is unconscious of his anima, he can be fully swayed and destructively influenced by her. When he becomes aware of her and her needs, she can inspire him and lead him to his own totality. In Jungian terms, the Popess would represent for the man a very high development of the anima. It is she who would symbolize the archetypal figure which relates him to the collective unconscious. For a woman, the Popess could be a highly differentiated form of Eros, she would symbolize womanliness, a spiritually developed self.

The reason that Nichols uses the word "anima" for

men and "Eros" for women is that for Jung only men had an anima;

women had a masculine "animus", correspondingly contrasexual. So

Nichols needed another Jungian term. "Eros," seen as connectedness,[103]

and in contrast to Logos, ideas, serves that purpose. Post-Jungian theorists

such as James Hillman, in contrast, modify Jungian theory, so that the same term

"anima" applies similarly to men and women: while "animus"

corresponds to the ego-complex, the anima in both men and women is that which

"pushes the individual . . . toward individuation," as Joan Relke puts

it in a summary of that view.[104]

Sometimes she appears to usurp his entire personality so that a man in this state seems almost to speak with her voice, in a womanish, irrational, and even hysterical way. One can imagine that the Moon goddess pictured in Figure 18 [an ancient statuette of the Sumerian goddess Astarte now in the Louvre, at right] might be vindictive and ruthless when crossed.

Likewise “Woman’s nature is moody, changeable as the moon, which can bring life-giving nurture, drought, or destructive floods, depending on the whim of the Great Goddess.” But women “are usually more aware of her influence and are prepared to deal with it.” In this regard, she says, Waite’s High Priestess looks “too good to be true.” [106]

In someone unconscious of the anima, or Eros, its negative traits will be projected onto others. The Popess as projection is among other things mythologically the witch, who produces love spells, makes people sick or die by magic even at a distance, drives those whom she hates mad, reveals the future in trickster ways, and is connected not with God (as a symbol of the Self) but the Devil. We might think here of the witches in Macbeth, whose ambiguous oracles are read by him as omens of success in his ruthlessly evil undertakings (goaded on, of course, by his wife). Such, in Jungian psychology, is Hecate or Diana as goddess of witches, a projection onto women, and some men, of all about themselves that men and women do not understand and cannot control. (Jung does not seem to have known about the Chaldean Oracles, as he regards Hecate in purely negative terms.) So it is she, too, who leads men into heresy, like the ghost of Guglielma and her priestess Manfreda in medieval Milan.

Yet it is such figures, in dreams and visions, that lead one to the experience of the self. In the dream of the black and white magicians (see my post on the Magician), the bones of a virgin, when taken out of their grave, turn into a black horse that runs off into the desert. This is an anima-figure, Jung says. Following it into the wasteland, the black magician finds the "lost keys to the kingdom." The "kingdom" is to be understood as the psychological equivalent of salvation, i.e. the revitalization of the personality. Many Popess/High Priestess cards actually show such keys, adopted by the Church to symbolize the papacy, On the card we also see an open book, presumably a sacred one, the reading of which is not the same as experiencing truth or the self, but it can lead to that experience, which so far is safely hidden behind her.

On the positive side, the "very high development of the anima" that Nichols speaks of fits the "stages of anima development" explicated by Jung in his book Psychology of the Transference (Collected Works, vol. 16, in archive.org, p. 173, para. 361).[109] He endorses what he says were recognized in late antiquity as "four stages of eroticism": Eve, Helen of Troy, the Virgin Mary, and Sophia.

Eve is merely the "instinctual" side of Eros, that is, the satisfaction of bodily desire, useful for propagating the species. In Faust, it is Faust's affair with the serving girl Gretchen.

Eve is merely the "instinctual" side of Eros, that is, the satisfaction of bodily desire, useful for propagating the species. In Faust, it is Faust's affair with the serving girl Gretchen.

Actually, it seems to me, the Biblical Eve is more than that: she is a figure in Adam's unconscious, leading him to the "happy fault" that alone will set the stage for humanity's eventual rise above even the angels. Nichols later in this chapter points to a painting by William Blake that captures the moment (at right; unfortunately some of the paint has flaked off over time). It is conventionally called "The Temptation of Eve," but Nichols prefers to call it "The Female from his Darkness Rose," a line from Blake's Gates of Paradise - a fitting place in which to situate her.

It is worth seeing that line in the context of the poem; it is the second line of the first section (after the Prologue), "The Keys to the Gates." The result of the serpent's temptation is a plunge not only into "Doubt, Self Jealousy and Watry folly," but also "Two-horned reasoning, Cloven Fiction," and "Rational Truth, Root of Evil and Good," - i.e., the split between good and evil engendered by Christianity, a veil that separates Adam from his imagination, which for Jung is how the unconscious is revealed to consciousness. Eve, born of the ego's shadow, is the first fruit of that imagination.

It is worth seeing that line in the context of the poem; it is the second line of the first section (after the Prologue), "The Keys to the Gates." The result of the serpent's temptation is a plunge not only into "Doubt, Self Jealousy and Watry folly," but also "Two-horned reasoning, Cloven Fiction," and "Rational Truth, Root of Evil and Good," - i.e., the split between good and evil engendered by Christianity, a veil that separates Adam from his imagination, which for Jung is how the unconscious is revealed to consciousness. Eve, born of the ego's shadow, is the first fruit of that imagination.

In the second stage of anima development, Jung says, the anima "is still dominated by the sexual Eros, but on an aesthetic and romantic level where woman has already acquired some value as an individual."

In a footnote he adds that "Simon Magus' Helen (Selene) is another excellent example" (besides Helen of Troy). This is from a heresy related by the 2nd century heresiologist Irenaeus: Simon (a Magician, let us note) found her enslaved in a brothel but freed her and took her with him as his companion.

If the Popess/Priestess represents a "high stage of anima development," the Popess/ Priestess does not fit either of the first two stages. But there is enough in her depiction to project onto her the Virgin Mary. She "raises Eros to the heights of religious devotion and thus spiritualizes him: Hawwah [Eve] has been replaced by spiritual motherhood. She seems particularly appropriate to Waite's image of a young woman with a cross on her front.

The fourth stage, of Sophia, Goethe's "eternal feminine," is "something that unexpectedly goes beyond the almost unsurpassable third stage: Sapientia." He continues:

How can wisdom transcend the most holy and the most pure?—Presumably only by virtue of the truth that the less sometimes means the more. This stage represents spiritualization of Helen and consequently of Eros as such. That is why Sapientia was regarded as a parallel to the Shulamite in the Song of Solomon.

For Sophia/Wisdom, what comes to mind first is the personification in the Wisdom books of the Hebrew Bible: the helpmate of the Lord, with him from the beginning, of whom Wisdom of Solomon 7:22 and 7: 26 declare:

For in her is the spirit of understanding; holy, one, manifold, subtile, eloquent, active, undefiled, sure, sweet, loving that which is good, quick, which nothing hindereth, beneficent, . . . For she is the brightness of eternal light, and the unspotted mirror of God's majesty, and the image of his goodness.

But how could such a being "less" than the Virgin Mary? One clue is the comparison to Helen of Troy. Helen is married to Menelaus, king of Sparta, for whom she apparently has no love. In Goethe's Faust, Part Two, one of Jung's sources for this stage, he even wants to sacrifice her and her attendants. Instead, she loves the son of a foreign king and runs away with him. In Faust, she escapes by means of Mephistopheles in disguise and falls in love with Faust. As for Eve, there is the transgressive element. But what is the spiritual equivalent? I will try to unpack Jung's comments about the fourth stage bit by bit.

One clue is his reference to the Shulamite of the Song of Solomon. Jung says in Aion of this figure:

The best-known anima-figure in the Old Testament, the Shulamite, says: "I am black, but comely" (Song of Songs 1 : 5). In the Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, the royal bride is the concubine of the Moorish king. Negroes, and especially Ethiopians, play a considerable role in alchemy as synonyms of the caput corvi and the nigredo. They appear in the Passion of St. Perpetua as representatives of the sinful pagan world.

That is a rather multifarious characterization. In Song of Solomon 1:5-6 (King James Version), we find:

I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem . . . Look not upon me, because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me; my mother's children were angry with me; they made me the keeper of the vineyards; but mine own vineyard have I not kept.

By "not keeping mine own vineyard," apparently, the text means that she has not kept her purity. The suggestion is that she has eluded her brothers' watchful eyes by having a lover, who has feasted on her "grapes" (2:15): "Take us the foxes, the little foxes, that spoil the vines," they say, after which she says (2:16): "My beloved is mine, and I am his: he feedeth among the lilies." So the disapproved-of lover has visited her. Later in the Song she suffers abandonment and persecution (5:6-7):

I opened to my beloved, but my beloved had withdrawn himself, and was gone: my soul failed when he spake; I sought him, but I could not find him: I called him; but he gave me no answer. The watchmen that went about the city found me, they smote me, they wounded me; the keepers of the walls took away my veil from me.

A veil is necessary for a betrothed to speak to her husband (Gen. 24:65). Or perhaps they regard her as a prostitute. She is looked down upon by family and society, seemingly abandoned by her lover, and can only be redeemed by his return. In that sense, "less" in a conventional sense is "more" in the mystical sense, a steadfastness regardless of social condemnation. If she is "black" because "the sun has looked on her," either the king has used her or a lover has. In the Old Testament the sun is also a metaphor for God.

In another place Jung quotes from an 18th century alchemical text which, after referring to the "watchmen who will find thee and wound thee," etc., has her reply (Mysterium Coniunctionis, p. 411, in archive.org),

Yet I shall be blessed again when I am delivered from the poison brought upon me by the curse, and mine inmost seed and first birth comes forth. For its father is the sun and its mother the moon.But first (par. 591, pp. 410-411):

I must be fixed on a black cross, and must be cleansed therefrom with wretchedness and vinegar and made white, that the inwards of my head may be like the sun or Marez [earth, Jung says] and my heart may shine like a carbuncle, and the old Adam come forth again from me. O! Adam Kadmon, how beautiful thou art!

Here the blackness, Jung says, comes from Eve's sin, which was also "the possibility of moral consciousness." What is in her is evidently the arcane substance of the Emerald Tablet, called here a "carbuncle" (a term for that substance, Jung says) and both "the old Adam" -sinful - and "Adam Kadmon" - the Primordial Man who is now the redeemer. So what results is a unity of opposites, sinful and prelapsarian, blackness and illumination. Less is more.

For Jung this text is a herald of his view that completeness is more realizable than perfection. Formerly "philosophy" held out the goal of turning lead into gold and of turning dark, "psychic" man into the higher "pneumatic" man. He continues:

But just as lead which theoretically could become gold, never did so in practice, so the sober-minded man of our own day looks round in vain for the possibility of final perfection. Therefore . . . he sees himself obliged to lower hisw pretensions a little, and instead of striving after the ideal of perfection to content himself with the more accessible goal of approximate completeness. The progress thereby made possible does not lead to an exalted state of spiritualization, but rather to a wise self-limitation and modesty, thus balancing the disadvantages of the lesser good with the advantage of the lesser evil.

For another amplification of the theme, there is Simon Magus and Helen, a myth that contains its own spiritualization. Jung mentions it only briefly, so I will turn to his source, the ancient heresiologist Irenaeus (Against All Heresies, I.23.2-5),who we must keep in mind was an unsympathetic reporter. For him, Simon declared himself to be none other than God himself, who had only to think of something, and it sprang to life from his mind.

Now this Simon of Samaria, from whom all sorts of heresies derive their origin, formed his sect out of the following materials:--Having redeemed from slavery at Tyre, a city of Phoenicia, a certain woman named Helena, he was in the habit of carrying her about with him, declaring that this woman was the first conception [Ennoia] of his mind, the mother of all, by whom, in the beginning, he conceived in his mind [Nous] of forming angels and archangels. For this Ennoea [Greek for "thought" or perhaps "first thought": MH] leaping forth from him, and comprehending the will of her father, descended to the lower regions, and generated angels and powers, by whom also he declared this world was formed. But after she had produced them, she was detained by them through motives of jealousy, because they were unwilling to be looked upon as the progeny of any other being.

Jung observes that "she corresponds to the much

later alchemical idea of the soul in fetters"; he gives numerous references to alchemical texts. As such, there is a resemblance to the

alchemical Mercurius, which I discussed in the post on the Magician. But

there is a difference in emphasis: she is no magician; and the emphasis is on her sufferings.

She suffered all kinds of contumely from them [the powers she created], so that she could not return upwards to her father, but was even shut up in a human body, and for ages passed in succession from one female body to another, as from vessel to vessel. She was, for example, in that Helen on whose account the Trojan war was undertaken . . . Thus she, passing from body to body, and suffering insults in every one of them, at last became a common prostitute; and she it was that was meant by the lost sheep. For this purpose, then, he [Simon] had come that he might win her first, and free her from slavery, while he conferred salvation upon men, by making himself known to them.

Irenaeus goes on about how Simon boasts of the benefits of salvation through him, without the Church's moral demands. The saved soul is somehow beyond good and evil, meaning (for Irenaeus at least) that it can devote itself to seduction and pleasure. From this we can at least see what a "spiritualization" of Helen of Troy would be: the divine helpmate of God, as in Proverbs, but with a nasty bout of humiliation by God's imitators. Irenaeus adds that "They also have an image of Simon fashioned after the likeness of Jupiter, and another of Helena in the shape of Minerva; and these they worship." Minerva of course is the Roman goddess of wisdom.

However, Helena is not, strictly speaking, Sophia, but Ennoia. Other Gnostic myths make the distinction, of which Irenaeus presents one in great detail (Against Heresies, chapters 2-5). Jung mentions it briefly in Aion and devotes several pages to it in Alchemical Studies. The protagonist of the myth is explicitly called Sophia and not Ennoia. Simon's Ennoia was "the mother of all," while Sophia is the lowest of thirty divine beings in the Fullness (Pleroma). This Sophia leaps forth, conceiving without her male consort a passion to know the Forefather (Propator), a thing impossible for her. Instead, she gives birth to a daughter "without form or figure," a mere "reflection," and she suffers "ignorance and grief, and fear and bewilderment," out of which the material world will be formed. She is eventually restored to her place, but her daughter, also called Sophia (as well as Holy Spirit and Achamoth), remains in the dark emptiness outside the pleroma. The story turns to her (Alchemical Studies, p. 334, paragraph 451, citing Irenaeus, Against Heresies, I, 4)

Christ, dwelling on high, outstretched on the Cross, took pity on her, and by his power gave her a form, but only in respect of substance, and not so as to convey intelligence. Having done this, he withdrew his power and returned [to the fullness], leaving Achamoth to herself, in order that she, becoming sensible of the suffering caused by separation from the fullness, might be influenced by the desire for better things, while possessing in the meantime a kind of odour of immortality left in her by Christ and the Holy Spirit.

Jung observes that the cross is "the medium of conjunction" by which his suffering on high mirrors hers. In Aion, his translation even has it that Christ "stretched her out through his Cross, and gave her form through his power," as though conforming her shape to his. The visit gives her a double nature (paragraph 457, p. 337):

On the one hand the anima is the connecting link with the world beyond and the eternal images, and on the other hand her emotionality involves man in the chthonic world and its transitoriness.

In the two Sophias, we can see a predecessor to Waite's upper and lower Shekinah, Binah and Malkhut. We can also find the "formlessness" of the unconscious and the "empty mind" ready to receive from above the emanations of Hecate.

Irenaeus has much more to say, but I will give just one more passage, skipped over by Jung. I think the beauty of the original shines through, even though Irenaeus himself regards it as a disgusting heresy (I, 4, :

This collection [of passions] they declare was the substance of the matter from which this world was formed. For from [her desire of] returning [to him who gave her life], every soul belonging to this world, and that of the Demiurge himself [i.e. Yahweh], derived its origin. All other things owed their beginning to her terror and sorrow. For from her tears all that is of a liquid nature was formed; from her smile all that is lucent; and from her grief and perplexity all the corporeal elements of the world. For at one time, as they affirm, she would weep and lament on account of being left alone in the midst of darkness and vacuity; while, at another time, reflecting on the light which had forsaken her, she would be filled with joy, and laugh; then, again, she would be struck with terror; or, at other times, would sink into consternation and bewilderment.

This account corresponds to the "flood from the unconscious," with all its attendant affect, in analysis. Such also is the condition of the unconscious without being united to consciousness.

Unlike Mercurius, who knows full well that he has been trapped and only wants out, to have power over his jailers, it is an achievement for this Sophia even to learn of her entrapment, and then all she wants is to end the separation from her parent.

Of her passions, perhaps the most palpable is her tears. Nichols finds the element of water a suitable image to associate with the High Priestess:[110]

The element with which she connects is water. In most creation myths, water is depicted as the original receptive, productive, form-building power. From the depths of the ocean, out of the cradle endlessly rocking, rose all creation--all forms of life. Out of the deep unconscious rose consciousness itself. For, as the individual embryo is contained and nourished in the amniotic fluid, so each individual identity is contained and nourished in the deep unconscious of every newborn babe. Thus it is from the unconscious that consciousness is born.

Robert Place, in his Tarot and Alchemy, 2000, says something similar. "The High Priestess is the ultimate ruler of Water, which is an archetypal symbol of the unconscious."

Eventually, according to the myth, Sophia-Achamoth is rescued by the Paraclete (Greek for "advocate" or "comforter"), her Savior (a newly created divine being) and placed in the Ogdoad, or 8th sphere; this is above the seven planetary powers, but still outside the fullness where her mother resides. That she is above the planets signifies that she is above the complexes they represent, perhaps having passed through them herself: they have been brought to consciousness So she is at the gateway to eternity, like the figure on the card of our interest. But what is her role there, before her return to the fullness at the end of time?

There is an alchemical version of this story that is also compatible with orthodox Christianity. In Mysterium Coniunctionis, Jung devotes some 56 pages (pp. 274-33) to Ripley's "Cantelina," a 38 stanza alchemical poem. An old, barren King (the Ancient of Days, no less), that he may enter the Kingdom of God, re-enters his mother's womb. She turns black - she is has no trace of immaculacy in the beginning - and then to various colors (corresponding to Sophia's rising through the planetary powers). Her bed-chamber is sealed, the heat is turned up, the womb expands, the foetus dies and decomposes, the mixture turns to white liquid. In that sense the contamination is washed away. Then "from the bed a ruddy Son doth spring / To grasp the Joyful Scepter of a King." A maiden also appears; both ascend to heaven, while he returns to conquer the world and give health and prosperity to all those who fear God. This is mostly just Christian doctrine applied to conditions into a laboratory. The only addition, if that, is that the mother acquires whiteness, i.e. purity, by removing impurities, in other words, becomes immaculate by her conduct in life: it makes up for original sin, although probably a certain grace from above is needed as well.

I come to the alchemists' Sapientia (Latin for Sophia). In Psychology of the Transference, Jung is mostly concerned with a classic alchemical text called the Rosarium Philosophorum. It has an account of the aqua sapientiae, water of wisdom. "Water as a symbol of wisdom and spirit can be traced back to the parable which Christ told to the Samaritan woman at the well" (CW 16, p. 274, par. 485), in which Jesus speaks of "a well of water springing up into everlasting life." For Nicholas of Cusa, mid-15th century, the well has three levels: "the well of the senses, the well of reason, and the well of wisdom" (Ibid., p. 275). The well of reason is "on the very margin of nature; there drink only the children of men, namely those whose reason has awakened and whom we call philosophers." The well of wisdom, deepest of the the three, "calls the thirsty to the waters of salvation that they may be refreshed with the water of saving wisdom."

For the alchemists there are also three waters of "our science," namely the God-given gift of the royal art and the knowledge it bestows. Jung says that the first is that of "chemical experiments," in which knowledge is gained from observation. The second is "the God-inspired sapientia which he could also acquire through a diligent study of the 'books,' the alchemical classics" (par. 486, p. 276) The third admonishes the reader to "Whiten the lado and rend the books lest your hearts be rent asunder."

Why "rend" the books? Jung gives a psychological interpretation of the difference between the second and third waters. The second brings the unconscious to consciousness by means of thinking and intuition, and that people sometimes think the work is done. But (Ibid., p. 276, and par. 489, p. 278):

an attitude that seeks to do justice to the unconscious as well as to one's fellow human beings cannot possibly rest on knowledge alone, in so far as this consists of merely of thinking and intuition. It would lack the function that perceives values, i.e. feeling, as well as the function de reel, i.e. sensation, the sensible perception of reality. . . .

Intellectual understanding and aestheticism both produce the deceptive, treacherous sense of liberation and superiority which is liable to collapse if feeling intervenes. Feeling always binds one to the reality and meaning of symbolic contents and these in turn impose binding standards of ethical behaviour from which aestheticism and intellectualism are only too ready to emancipate themselves.

In our card, the Popess or Priestess invariably holds a sacred book, the Bible or Torah. It is the means for undertaking the second stage and appreciating its significance. Place observes:[111]

She acts as a messenger that surfaces from unseen depths, bringing inner wisdom to our conscious awareness. She encourages us to see what is hidden, to read between the lines, to find subtleties, nuances, patterns, and connections. This is the card of intuition, dreams, and esoteric knowledge, but in its simplest form it may only be a reference to silence.

Yet she is still far from yielding up all her charms. Place’s “to read between the lines” suggests intuition and thinking: the book's words and images suggest truths hidden behind the veil, just as the interpreters of texts

such as the Bible see levels of meaning behind or above the literal one. It is the same for dreams, fairy tales, artistic productions, and rational arguments, some

along well-trodden paths and others “a product of the most

complex and differentiated minds of that age.”[112]

In that context, in place of the “celestial” and “supercelestial” gods of

Iamblichus,[113]

the tarot has the archetypes of the individuation process, of which the Popess/Priestess shows both the immediate tasks (in what we see) and hints of long-range ones (in what we don't see). For the latter, the first requirement is silence, not just verbally but mentally as well, the "empty mind" advocated by the Chaldean Oracles.

As a wordless commentary on “silence,” Place ends his section on the Priestess

with a picture from the 1677 Mutus Liber; it shows the alchemist

and his Soror Mystica (Mystical Sister) making the sign of silence, i.e.